When a global crisis becomes a regional issue

- Published

Did you hear the one about local garden centres?

"We shall monitor it locally and regionally"

It wasn't the most headline-grabbing part of Boris Johnson's latest televised broadcast to the nation. But as the BBC's political editor in one of the English regions worst hit by the pandemic, this was the moment when my ears pricked up.

Just days earlier I had jokingly talked on one of our radio programmes about the possibility of "un-lockdown" being implemented differently in different areas, depending on how those all-important numbers worked out.

"Could we see hoards of Brummies descending on the garden centres of Gloucestershire," I laughed, "while their own remain firmly shut?"

In the event, all England's cherished garden centres are being allowed to open this week. So why that prime ministerial talk of local and regional monitoring?

As I prepared to ask the West Midlands' Conservative mayor, Andy Street, his first reaction to the new advice for Midlands Today's late news, I wondered how he might view the prospect of some regions reopening for business ahead of his. After all, it's one of those things "everybody knows". Everybody knows the West Midlands has been at or near the top of the depressing daily toll of Government graphs since the start of the crisis.

Except that when the camera started turning, Mr Street confounded me with "good news". After what he conceded had been "a bad start", our part of the country was now recovering faster than most. At the time of writing, I find that out of the UK's current total of 223,000 confirmed Covid-19 cases, the West Midlands accounts for just over 11,000 - fewer than one in 20 in a region which in broad terms accounts for nearly one in ten UK people.

"The despair I can handle, it's the hope!"

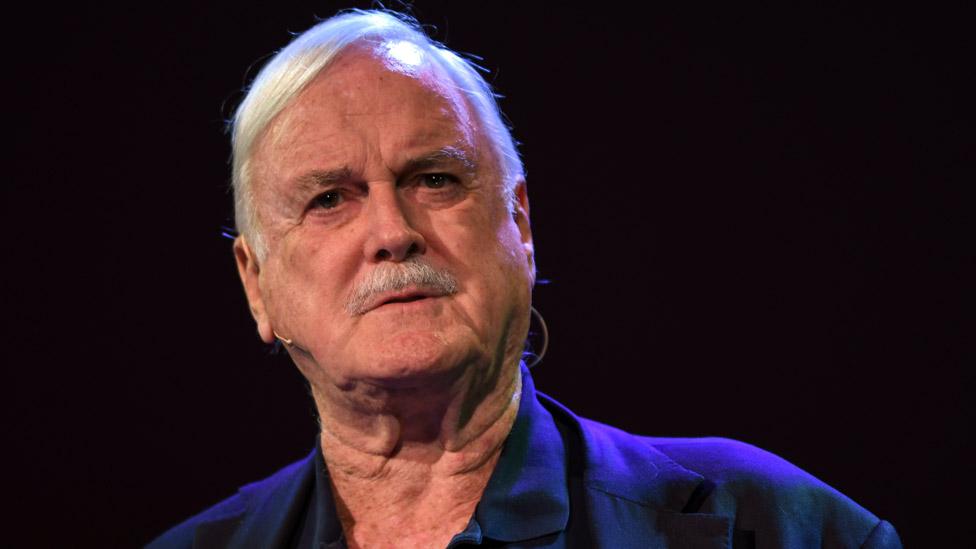

So said John Cleese when things took an unexpected turn for the better in the epic comedy movie Clockwise, which was filmed largely in Birmingham. Just when he was reconciled that all was lost, came the sudden realisation that circumstances were conspiring to require him to make yet another exhausting effort to keep his flagging hopes alive.

Local v regional: Just don't mention the lockdown war

So having accepted that "local and regional" monitoring could mean only more of the same for us citizens of Lockdownland, could we now be presented with a tantalising and frankly rather unsettling glimpse of something better? Maybe we weren't, after all, at the forefront of Boris Johnson's mind when he warned the Government "will not hesitate to put the brakes back on" if necessary.

It's now clear that this gradual, phased, unlocking will be accompanied by the threat of an immediate re-locking anywhere that shows the "R Rate" (don't ask!) heading back north of one. I'm told this would be applied not to entire regions all in one go, but to individual cities, towns or districts which showed signs of becoming hotspots.

We'll see.

The other new message is that after being told to stay at home, work from home if possible, and go to work only if necessary, people are now being advised that those, for example, in construction or manufacturing, who can't work from home, are "encouraged to go to work". Our biggest local carmaker, Jaguar Land Rover, is due to resume limited production next week.

Sir Keir Starmer accused the government's plan of a lack of planning

Initially, the Labour Leader, Sir Keir Starmer, accused the Prime Minister of telling people to go back to work without giving them a plan for their safety. The four biggest unions warned people should return to work only if their employers were ordered to take necessary precautions. The Government's more detailed explanation next day of how the new rules would be implemented were interpreted by the TUC general secretary, Frances O'Grady, as no more than "a step in the right direction".

Borderline questions

This debate about how we restart the economy is only just beginning. And again it's beset by regional and national border tensions.

I know from my own experience how heavily local communities on the English side of the Herefordshire border depend on the shops and business at Monmouth in Wales, where the advice remains unchanged: "Stay Home". And talk about "life on the edge": the village of Llanymynech straddles the border between the Welsh county of Powys and Shropshire. The Cross Keys pub is half in Wales and half in England. So will some of the "locals" who in happier times frequent its bars be able to go alertly about their business while others remain locked down?

And then there's JCB, who we describe on our regional news programmes as "the Staffordshire digger-maker", conveniently ignoring the fact that they have factories not just at Rocester but also at Wrexham in Clwyd: a challenging arrangement, surely, as they begin their orderly return to work.

As I said at the end of that Midlands Today report:

"We're about to find out how much more challenging it is politically to unlock the lockdown, than it was to impose it in the first place."