My retirement and the new meaning of legacy

- Published

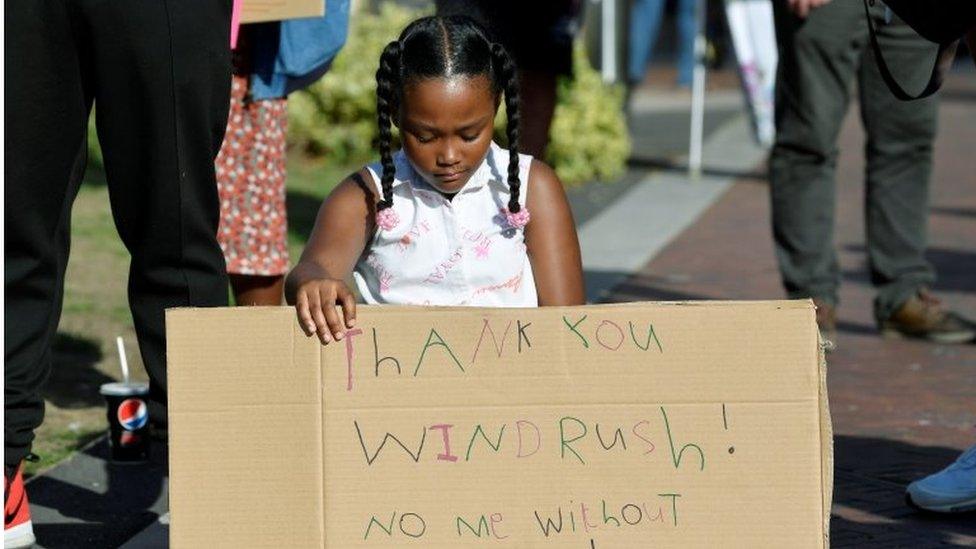

Me as the first picture? You might think it's about legacy, but I couldn't possibly comment

Breaking news

It always makes me cringe. My skin creeps when a journalist allows themselves to become the story rather than the storyteller.

"Absolutely right", I muttered to myself, when I read the Sunday Times interview with the distinguished BBC Television News presenter George Alagiah last weekend. He told us that he doesn't believe he should be talking about his own opinions while he is a newsreader.

Take note, some of our lesser journalistic mortals who seem to view their broadcasting roles as useful adjuncts to their social media profiles.

Oh dear! Have I just expressed an opinion? Perhaps I can take a liberty just this once, now that I am about to stand down from our own news output.

In a flagrant breach of my self-imposed protocol, I "went public" last week with news of my impending retirement. How else was I to explain why Midlands Today is running a series of reports reflecting on some of the groundbreaking events I have witnessed over my 45 years in the BBC?

Any inhibitions I may have felt have been overwhelmed by my amazement at the generous messages I have since received: far too many for me to reply individually. But....

Thank you

An essay written by C.P. Scott 99 years ago to mark the centenary of The Guardian newspaper of which he was himself the legendary editor for more than half a century also seems uncannily appropriate: "Comment is free", he wrote, "but facts are sacred".

The first of my "specials" went out during last Wednesday's Midlands Today and the next two are due to be transmitted on the Wednesdays of this week and next, though they may be shunted back by a day or two in the event of yet more "breaking news".

Each of them involves a brief scene-setter in which I cut my own distinctive slice of one of the defining themes. That's followed by an extended interview with someone who has been at the centre of those events.

Last week, I examined links between the Handsworth Riots in Birmingham back in the 80s, through the Windrush Scandal, to the Black Lives Matter movement now.

I then interviewed Dr Derrick Campbell. I first remember him as an energetic anti-discrimination activist in Sandwell and West Birmingham nearly 40 years ago, He's now one of England's five regional directors of the Independent Office for Police Conduct, which has been investigating nine allegations of excessive force by West Midlands Police officers against black people during the past year alone.

He agreed with my suggestion that the riots, Windrush and the renewed debate following the death of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis are connected by what he called "a continuum of frustration".

Soaring unemployment in Handsworth was a prime factor back then and Dr Campbell warned that, as we emerge from Covid into the worst economic downturn in living memory, there is a danger that some people in deprived areas "will do whatever it takes to survive".

Still to come

My Midlands Today package this week turns to the troubled aftermath of the IRA bombings of two Birmingham pubs in 1974, the year before I joined the BBC. I went on to cover Northern Ireland's "Troubles" during my four years based in our Belfast newsroom. But by the tenth anniversary of the bombings I was back in my native Birmingham as a Midlands Today news reporter.

At least, by then, justice had been done. Or so it seemed. Six men were serving life for their part in what was still the worst terrorist atrocity on either side of the Irish Sea.

Twenty-one people died in the explosions in November 1974

Six years later, with the acquittal of the Birmingham Six, came the definitive recognition that, after 16 years behind bars, each of them had been the victim of a catastrophic miscarriage of justice. It also meant there had been no justice either for the 21 people who died.

Among them was 18-year-old Maxine Hambleton whose sister Julie continues her tireless campaign for the real perpetrators to be rounded up and convicted.

Until then there can be no "justice for the 21", she tells me, in the second of my set-piece interviews. She brands British justice "the laughing stock of the world".

Following last year's inquest which recorded verdicts of unlawful killing, she now plans to run for West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner in elections due next May.

But how is she, as a single-issue campaigner, qualified for a major political office which carries such wide public responsibilities? Her answer is characteristically robust but you'll have to watch Wednesday's Midlands Today (subject to change) to find out what it is.

Next week

During next Wednesday evening's programmes (again, subject to change) I'll relive the rollercoaster ride that is Midlands business and industry.

I reported on the heyday of the so-called "union barons" during the 1980s, among them Derek Robinson, aka "Red Robbo".

Those mass union meetings and the strikes they triggered at Birmingham's now-defunct Longbridge car factory became emblematic of "the British disease". That was until the Thatcher government outlawed the now-notorious shows of hands.

Over the next two decades I witnessed the slow death of what was then the British motor industry culminating in the tragicomedy of the "Phoenix Four" and the false hope they offered to the 6,000 workers who lost their jobs in 2005 when the collapse of MG Rover could be put off no longer.

It took another decade for Jaguar Land Rover to prove that when unions and management work constructively together they can become world-beaters.

By then, many of our great Midlands industries, including iron, coal and steel had vanished, leaving structural unemployment and endemic deprivation in communities, some of which have yet to recover.

As a young news reporter, I covered some of the most violent confrontations during the year-long miners' strike of 1984-85.

It still reverberates through my memory like a civil war between the striking National Union of Mineworkers and the Union of Democratic Mineworkers, despised by the NUM's flying pickets as a "scab" union for working through the dispute at pits in Staffordshire and Warwickshire.

Since then we have seen the rise and rise of global industrial successes including the Staffordshire digger-maker JCB, which supported Boris Johnson in his Brexit campaign and gave him the bulldozer he needed to smash Labour's wall.

We know about JCB, but what about JOBs?

But what comes next, as we face up to the looming economic downturn?

My final interview is with one of our most influential figures on the business scene, who used to drive past Longbridge on his way to his office in a Birmingham commercial law firm.

Digby - now Lord - Jones went on to become the director general of the CBI, then Minister for Trade and now a crossbench peer.

Having observed so many of those ups and downs, he now predicts millions of people will lose their jobs.

In his own inimitable style he concludes: "I believe the small businesses of the West Midlands will bring our economy through. But it ain't going to be easy, that's for sure."

And finally - what's in a legacy?

I am due to return, for one last time, to Midlands Today on Thursday 3 September, my last day in the BBC, to reflect on my final chapter as a Lobby journalist and presenter of hundreds of Sunday morning political programmes over 22 years: Midlands at Westminster, Politics Show and Sunday Politics.

I have noticed how our leaders become increasingly obsessed with their legacies as their careers wear on. How will history judge them? What will they be remembered for? When I started out, a legacy was generally considered something beneficial inherited from the past.

Now, though, it's developed an almost opposite meaning.

A legacy airline is one struggling to offload its overweight baggage: costs and outdated working practices which hamper its ability to compete with the more agile "budget" carriers who have reinvented effective service delivery at affordable prices.

Legacy or "rust belt" industries are those which have been ruthlessly overtaken by the advance of new technologies and the fast-changing customer demands.

It came home to me, literally and very forcibly, just the other day.

I was connected to the office by my BBC laptop via the Remote Access System which I have marvelled at for years. It has enabled me to perform so many of the tasks I could once complete only by being physically at my desk, or "work station". My magic "RAS token" has certainly been working overtime during the pandemic.

Then came the bolt from the blue. Computer says no! My beloved Remote Access System was to be scrapped in barely a week's time because of some serious, but unexplained, "issues". Then came the killer blow: "It is a legacy technology" concluded the message, instructing users like me to switch to a new way of connecting.

Now that I have been forced to embrace this innovation, I find it is a vast improvement!

Ok, I take the hint. This is no time for a legacy political editor, in what will be a much-changed political landscape, post-Covid, with very different ways of working. It is the right moment for a new political editor to take up the story. I wish them well.

I shall be watching of course. And I hope you will too.