Channel crossings: Why can't the UK stop migrants in small boats?

- Published

The numbers crossing the Channel "remain low and manageable," the UN Refugee Agency says

The government has said it is committed to stopping migrants making the perilous journey to the UK in small boats. Why is it so difficult?

Towards the end of August 2019, ministers in the UK and France jointly pledged to make crossings by migrants in small boats an "infrequent phenomenon" by spring 2020, external.

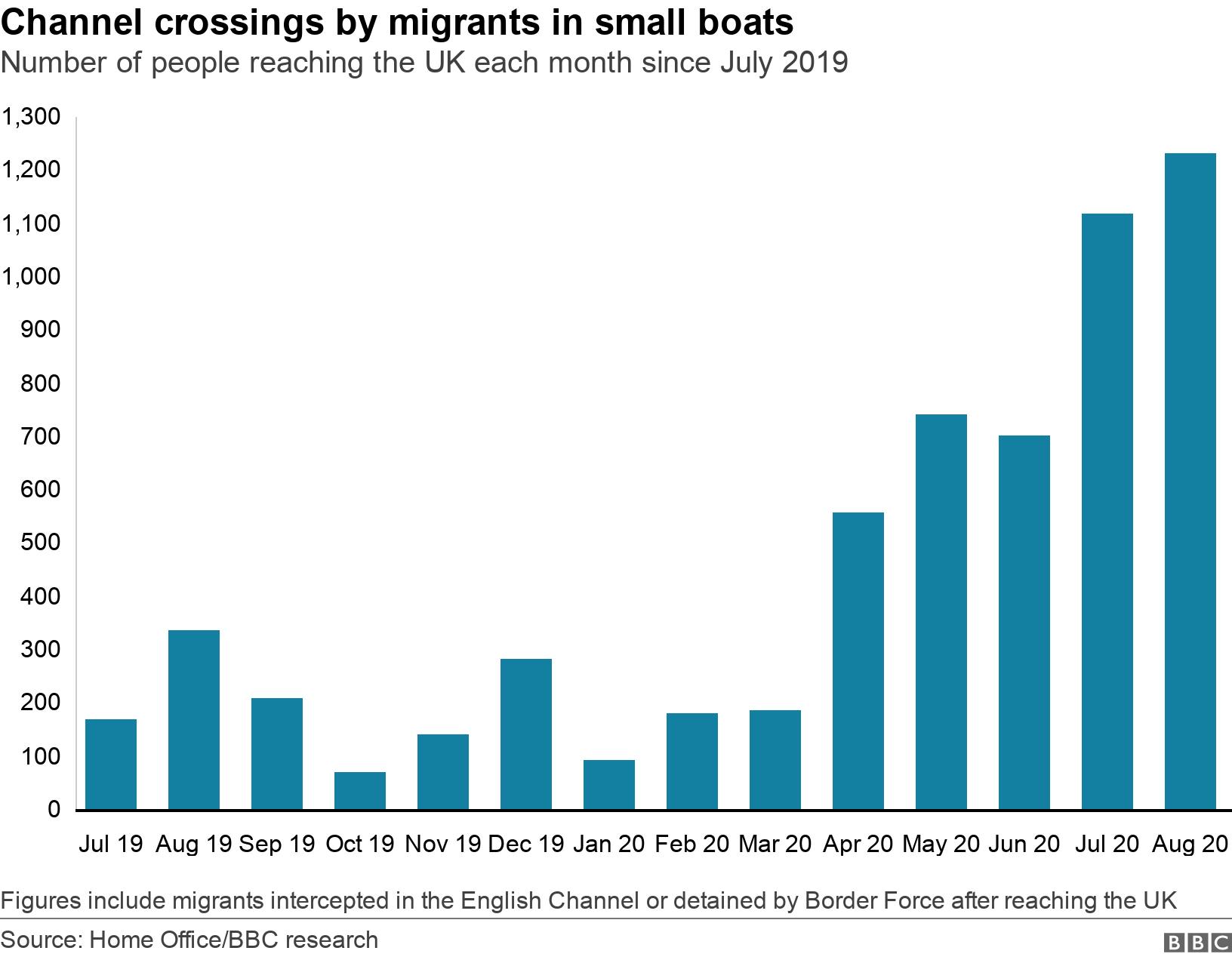

When Priti Patel met her counterpart in Paris last summer, about 1,400 people had already made it to the UK by small boat within the previous 12 months - and at least two lives had been lost.

Since then, a further 5,500 people have navigated one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world to join them.

The UK has spent £5.5m to try to end the crossings. Why hasn't it worked?

Stopping boats at sea

The home secretary has said she wants to make the route "unviable" and end demand by returning boats to France.

But, French authorities believe they are unable to intervene in many instances, because of differing interpretations of international maritime law, she added.

Hundreds of boats have been intercepted by Border Force in British waters

Calais MP Pierre-Henri Dumont said the most important thing was to ensure no more lives were lost.

"We are talking about human beings, we are not talking about cattle," he said.

The UN Refugee Agency said it was "troubled" by the plans to intercept and return boats, adding that the numbers making the crossing "remain low and manageable".

"The foreseen deployment of large naval vessels to deter such crossings and block small, flimsy dinghies may result in harmful and fatal incidents, external," it said.

Both international treaties and national laws determine what states can do at sea, said Dr Felicity Attard, a lecturer in international maritime law at the University of Malta.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, external, a country has the right to act in its waters when faced with an "inbound vessels carrying migrants which are intending to commit a contravention of the coastal state's immigration laws," she said.

But any action must also "take into account humanitarian considerations, for example, the need to protect the rights of asylum-seekers," which are protected by the European Convention on Human Rights, she added.

Migrants are returned to France after being rescued from a stricken dinghy

Any force used to return migrant boats to France "may only be used as a last resort, if necessary, proportionate and justified to achieve a legitimate aim," she said.

Ultimately though, Dr Attard believes that "given the safety issues both to the migrants on board and to international shipping, should it wish, France would be entitled to intervene".

However, the duty to "render assistance and protect life at sea remains paramount throughout," she added.

Sending people back

Since January 2019, 155 people who crossed the English Channel in small boats have been returned to Europe. A further 166 are due to be returned, the home secretary said last month. That is about 6% of the 5,500 people who made it to the UK since the start of 2019.

EU regulations known as "Dublin III", which determine where an asylum-seeker's claim is heard, were being used to "frustrate the returns of those who have no right to be here," the Home Office said.

The RAF has sent a transport plane to help spot migrant boats off the coast of England

Prime Minister Boris Johnson suggested the government would review laws that make it "very difficult to then send [migrants] away again even though blatantly they've come here illegally".

But, any new system will require support from the EU countries that asylum-seekers are being returned to, immigration barrister Colin Yeo said.

"If you want to send somebody to France, then you have got to do it with French agreement, you can't just launch them on a rocket into French territory," he said.

Without a new agreement at the end of the Brexit transition period in January, the UK would "go from a situation where it's not easy necessarily to remove people to EU countries, to a situation where it's impossible because there is just no way of securing their agreement to accept people back," he said.

Preventing boats departing

Since October 2019, the UK has paid for 45 French police officers to patrol the coastline. Additional officers from French border police are also patrolling.

More than 47% of attempted crossings have been prevented either at sea or before departing in 2020, according to the regional government in Calais.

Last month, police stopped 10 times more crossings than in July 2019, it said.

Migrants setting out to sea 20 miles east of Calais were filmed by a BBC team

But, the sheer scale of the 200-mile stretch of coastline, which is populated by quiet beaches lined with sand dunes, makes it impossible to stop boats setting sail altogether, French officials say.

"We are doing a lot but there are limits to what humans and technology can do stop people realising their dream," said Mr Dumont.

Stopping the gangs

The Home Office said it was pursuing the "heinous criminals and organised crime networks" behind the crossings.

This year 23 people smugglers have been jailed and two more were charged earlier this month.

Two men were jailed after Mitra Mehrad drowned

Two men were jailed in France in December 2019 for helping organise a crossing in which Mitra Mehrad, a psychology PhD student from Iran, drowned off the coast of Kent.

In January, 23 people were arrested in France and the Netherlands on suspicion of smuggling 10,000 Kurdish migrants into the UK in lorries and small boats.

And yet, the number of people arriving on UK shores in small boats continues to rise.

Authorities believe that a reduction in freight on cross-Channel ferries and trains due to coronavirus has driven more people into the hands of people smugglers organising small boat crossings.

Authorities believe not all crossings are organised by people smugglers

Steve Reynolds, of the NCA, told the BBC in January there was no evidence of a single gang behind the crossings.

Officers had focused on cutting off the supply of boats and engines, but smugglers, who are believed to charge migrants several thousand pounds per place, took to sourcing boats further afield including the Netherlands and Germany, he said.

Meanwhile, some migrants "self-facilitate", by acquiring a boat themselves and making their own way, Mr Reynolds said.

On 6 August, the French rescued seven people from three kayaks, with a further five inflatable kayaks believed to have made it to the UK. Some of the models used can be bought from sports retailers in France for as little as €300 (£270).

Staying in France

The Home Office has said that, instead of crossing the English Channel, people should seek sanctuary in France, which is a "safe country with a well-functioning asylum system".

But the UK only receives a small proportion of all asylum seekers, with many settling in other European countries, said Clare Moseley, of Care for Calais.

"It's a real misconception that all refugees want to come to the UK," she added.

France, which has a similar population and economy to the UK, receives more than three times as many asylum applications, according to EU data, external.

Across the EU in 2019, the rate of asylum applications averaged 14 per 10,000 residents. In the UK, it was 5 per 10,000, external.

Parts of the "Jungle" camp burned as it was demolished in 2016

The government has used some of the £5.5m spent to deter crossings - much of which went on technology like CCTV and night-vision goggles - to finance a "strategic communications campaigns" to deter people from making the crossing.

This has included "delivering direct messaging to migrants," the Home Office said.

"Occasionally it works, but in general Calais is the last destination," Ms Moseley said. "Most of the people who come here have decided for one reason or another that they want to get to the UK, it's kind of a bit late then."

Many have lost family members in conflicts and want to join surviving relatives already living in the UK, she said.

Several makeshift camps in Calais were cleared by police in July

The tactics of French police have made it harder to dissuade those gathered in Calais from heading to the UK, she said.

Since the infamous "Jungle" was cleared in 2016, smaller camps are regularly evicted and the last police operation, in mid-July, was "pretty horrific" and involved "a lot of violence and tear gas," she said.

"People who have got scars on their bodies from French police are not going to want to stay in France," she added.

The French interior minister has been contacted for comment.

In 2017, following a report by Human Rights Watch, external alleging abuses by police, the then-minister said officers were working in a challenging environment, stopping thousands of attempts to illegally enter the Port of Calais and Channel Tunnel.

Other solutions

Refugee charities and French politicians have long said the solution must be to allow would-be asylum seekers to apply for sanctuary before they arrive in Britain.

Mr Dumont has called for migrants to be allowed to claim asylum at British embassies across Europe.

"What we would really like to see is safe and legal routes," Ms Moseley said.

She would like people to be able to make applications at the British border controls in Calais, rather than needing to land in the UK.

"Focusing on security and deterrents does nothing more than brutalise people," she said.

- Published20 December 2019

- Published15 July 2020