Menace to sobriety: When Salvationists fought Skeletons

- Published

A young woman, newly married, was knocked to the ground in the English seaside town of Hastings. She was targeted because of her religious beliefs and the clothes she wore, felled by a thrown rock and kicked in the stomach by a mob. She lost an eye. Then later, in hospital, she died from internal injuries.

It was 1889 when Susannah Beaty became the Salvation Army's first "martyr".

The tail end of the 19th Century saw towns across the south coast of England descend into violence. Dead animals, some set alight, were hurled at passing Salvationists, as were sticks, stones, paint-filled eggs, burning coals and rotten fish. Chamber pots were emptied from upper windows over the heads of men and women below. Thousands of people were injured, some were killed.

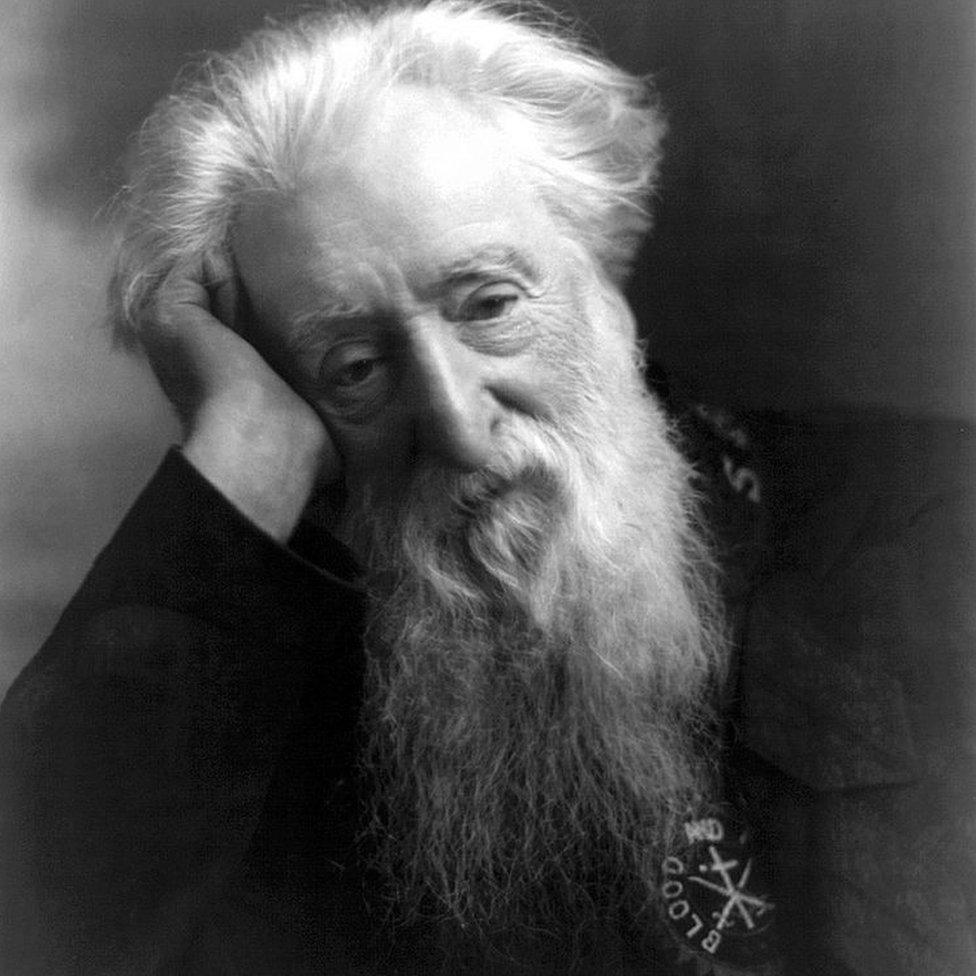

The founders of the Salvation Army - originally known as the Christian Mission - William Booth and his wife Catherine, preached and lived out a doctrine of practical Christianity.

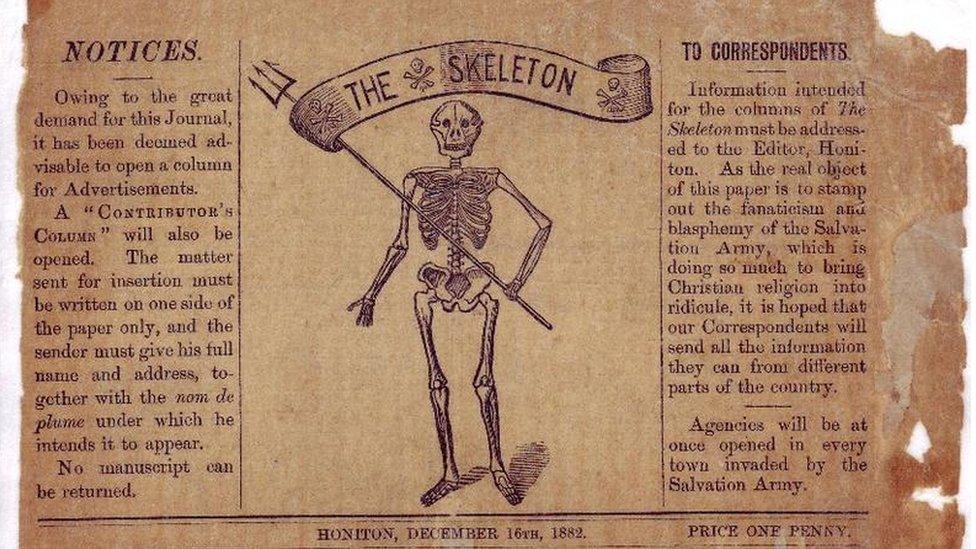

And a rival force - a ragtag yet violent band calling itself the Skeleton Army - was determined to throw a spanner in the good works.

William Booth, a former pawnbroker's assistant from Nottingham, founded the Christian Mission which became the Salvation Army

For some, England in the late Victorian era could be a difficult, dangerous and depressing place to live. A significant portion of the working classes suffered from extreme poverty, disease and hunger. But the organisation offering food, shelter and spiritual succour was not wholly welcomed by those it set out to help.

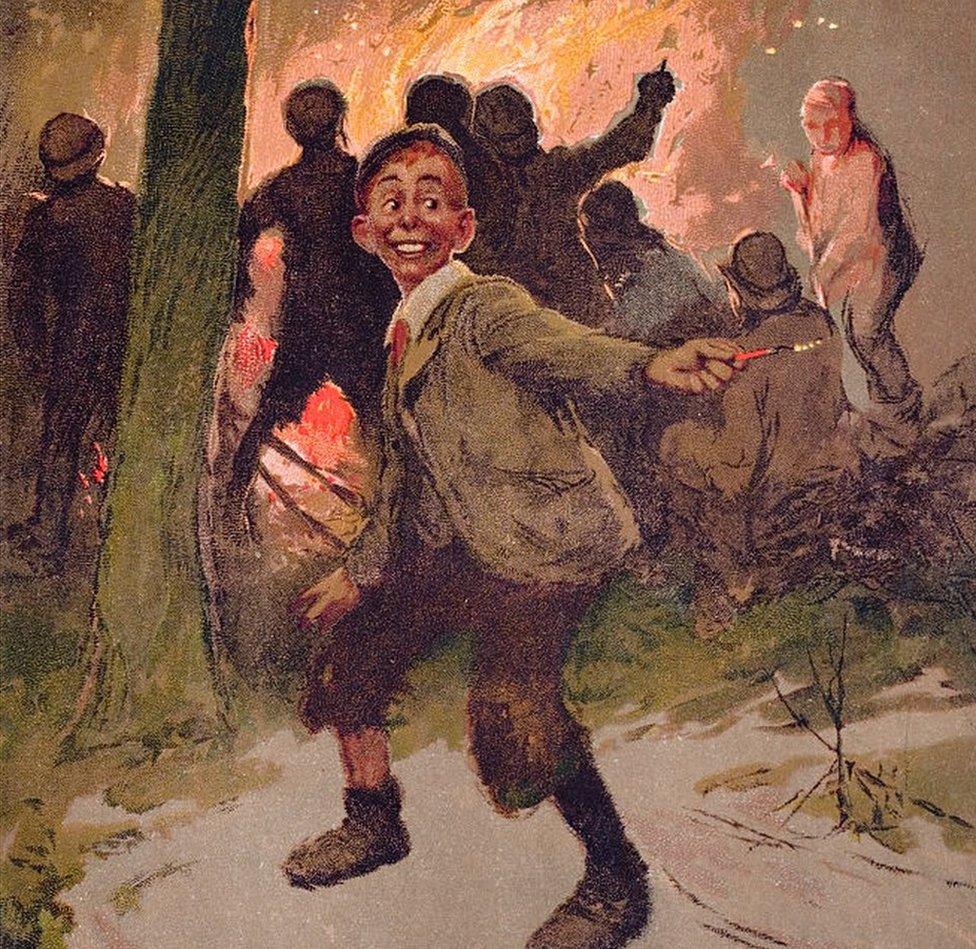

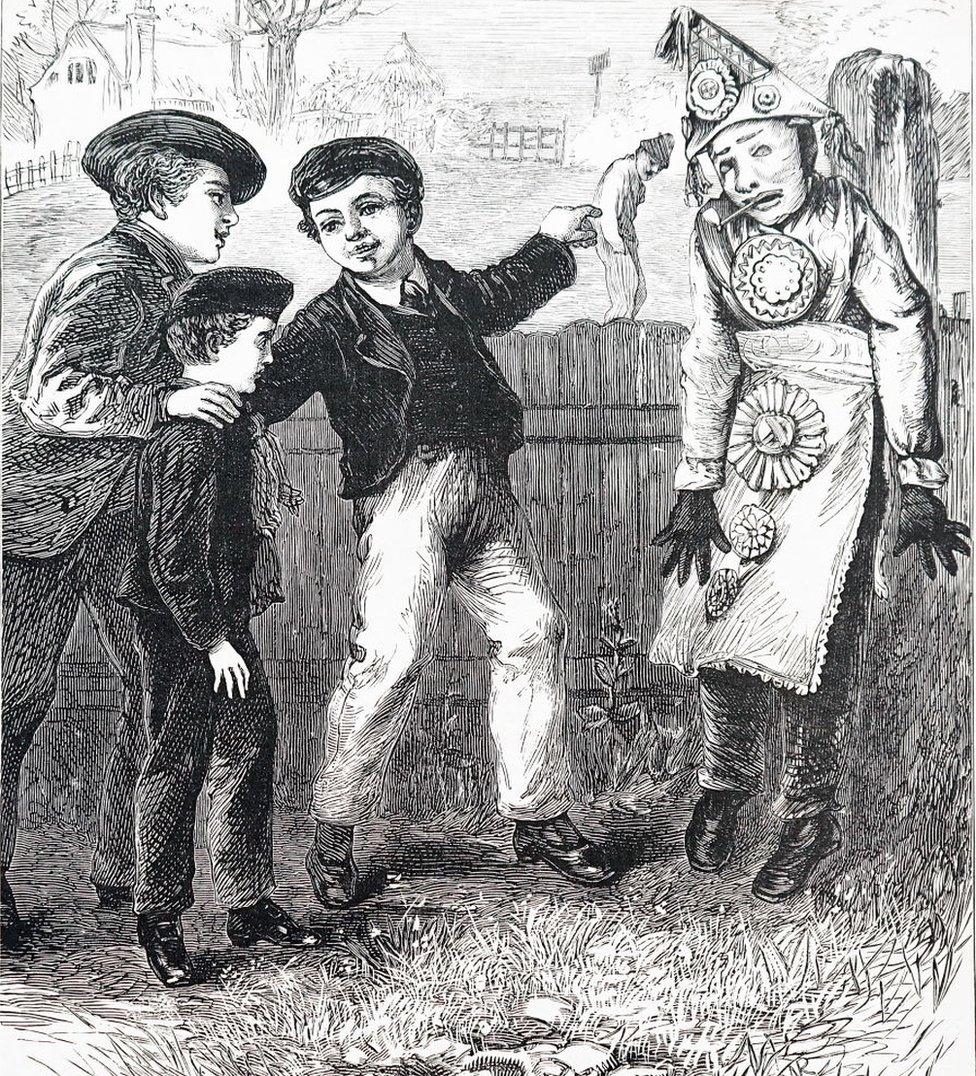

The rebel group's roots were in the "Bonfire Boys" of towns on the south coast of England - young working-class men who built fires, burned effigies and in some cases, bowled flaming barrels of tar along the streets.

They enjoyed nights of revelry and roughhousing, fireworks and fisticuffs and were always unlikely to be attracted to an organisation dedicated to abstinence and cleanliness.

Chris Hare, a historian from Worthing - one of the hotspots of Skeleton activity - says the revolts were the "final violent expression" of traditional working-class festivals and celebrations, such as Bonfire Night and May Day.

Bonfire Boys were common in towns across the south of England

By the 1860s, widespread industrialisation meant more people were living in urban rather than rural areas - but casual and unskilled workers often still struggled to find employment, while missing out on the fresher air and better food of the countryside.

Housing could be overcrowded and insanitary. Hand in hand with industrialisation came workplace accidents, with little hope of recovery and no social support.

Beer and gin were cheap and easily available, and numbed reality or provided a much-craved pick-me-up.

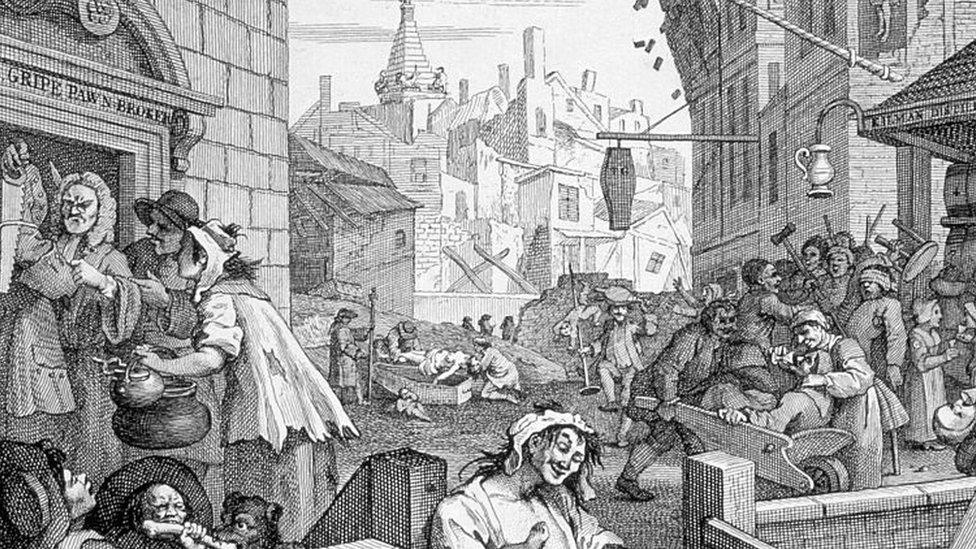

It was into this Hogarthian dystopia that preacher (and former pawnbroker's assistant) William Booth and his merry band marched, on a crusade to convert the masses to clean living, Christian worship and moral integrity.

Specifically targeting the poor with evangelical zeal was a bold move at the time, but Booth and his followers were determined to spread the word and save some souls.

Followers were urged to not only give up the demon drink, but "lowbrow theatre", gambling and "lascivious pastimes".

Darkest England knew where to place the blame for sin

A grim - if well-intentioned - publication called The Darkest England Gazette was produced by the Salvationists, with the remit of "voicing the miseries and pleading the necessities" of those lured into music halls, which are described as "trapdoors to vice".

But the Salvationist ethos was not all restrictive - in addition to wanting to prohibit alcohol and end prostitution, they gave equal status to women within the organisation.

As Mr Hare points out, this was some 25 years before the suffragettes - and 50 years before all women - got the vote.

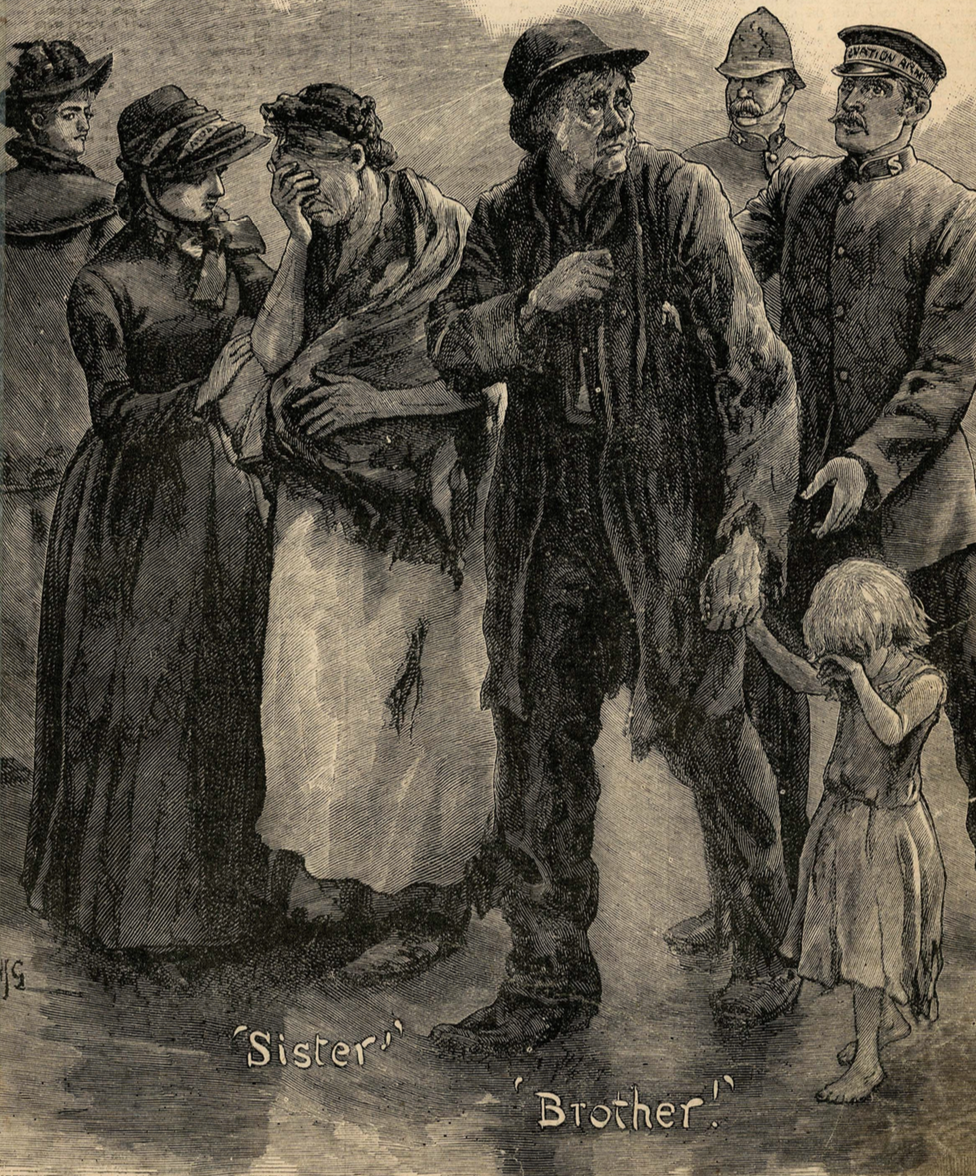

Women in the Salvation Army were given equal status to men

In contrast, Mr Hare compares the Skeletons to modern-day football hooligans, or the English Defence League.

"Although assertively working class, they were not in any sense revolutionary. In fact, they were very conservative. On the other hand, the Salvation Army was revolutionary in a social, if not political, sense."

And that revolutionary spark was a worry for the better-off, who had a financial interest in maintaining the status quo. The last thing they wanted was a band of sober, upright workers demanding proper pay and adequate conditions.

The landowners and factory-owners did not have to lift a finger in opposition to the Salvationists. The lower classes did their dirty work for them.

Hogarth's Gin Lane depicts the evils of strong liquor, albeit in Georgian rather than Victorian England

Libertines, drunkards, publicans and brothel-keepers all joined the ranks of the Skeletons, who found plenty to mimic and mock in the Salvation Army's militant manner.

Although the Salvationists originally concentrated on prayer and preaching, they soon realised that people found it hard to think about the state of their souls if they were preoccupied with getting food or shelter. The Salvation Army started supplying both, attracting supporters with the principle of "soup, soap and salvation".

Not everybody was keen on that mantra - some saw the provision of soup as inadequate recompense for being lectured about washing or being told to stop going to the bawdyhouse.

The Salvationists wore uniforms, carried banners and assumed soldierly nomenclature. That, along with their holier-than-thou attitude, proved to be extremely irritating to many ordinary people.

Tug Wilson, editor of anarchist magazine Now or Never, says the Salvation Army's unconventional approach "was abrasive to both the Christian establishment and many of those they were preaching to.

"In choosing to attack popular working-class pastimes, they whipped up a violent grassroots reaction and their provocative style of disseminating their message often resulted in public disturbances.

"Very soon Skeleton Armies started appearing throughout the country."

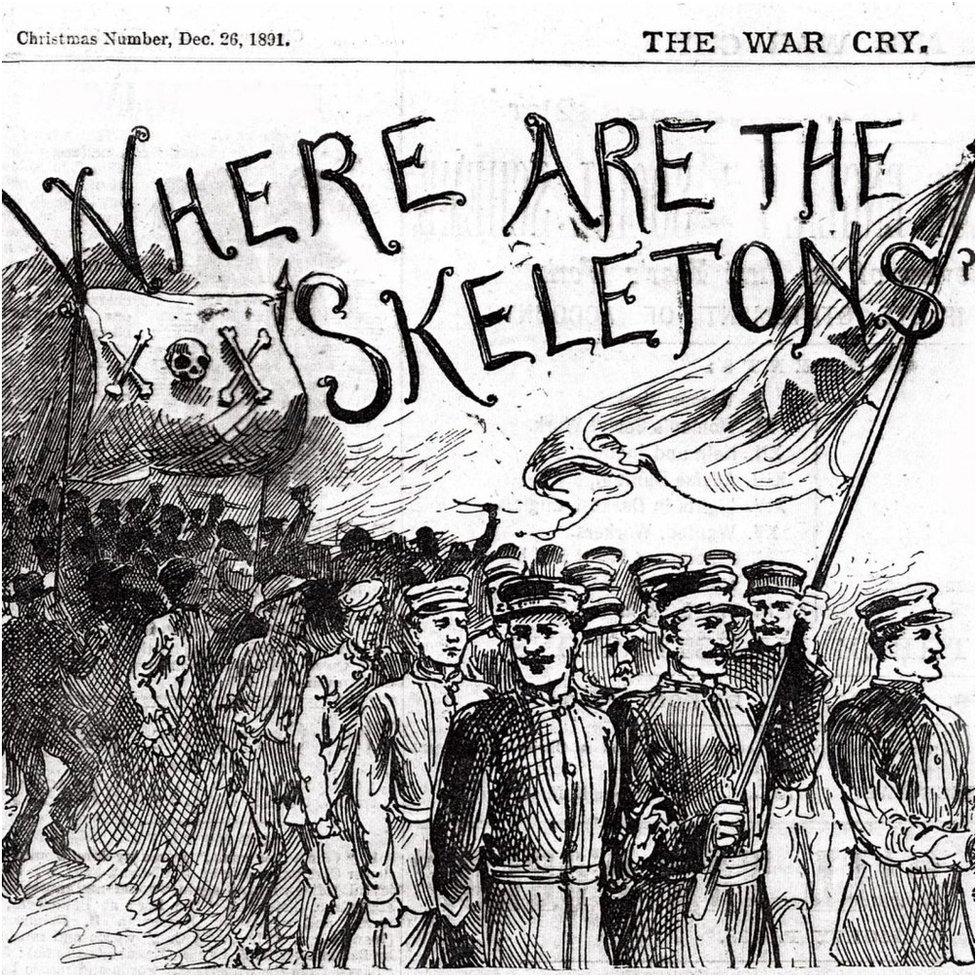

The Salvationists' newspaper The War Cry mounted a vigorous campaign against the Skeletons

The Salvation Army was not easy to ignore. It did not go quietly about its mission, or restrict its preaching to the pulpit. It took to the streets, bold and brash. It marched in processions, banging drums, flying banners, singing loudly and playing instruments.

It pilfered from popular tunes and put new lyrics to them. Champagne Charlie became Bless His Name He Sets Me Free; Here's to Good Old Whiskey became Storm the Forts of Darkness.

As Booth said in 1883: "We make the very enemy help us fill the air with our Saviour's fame."

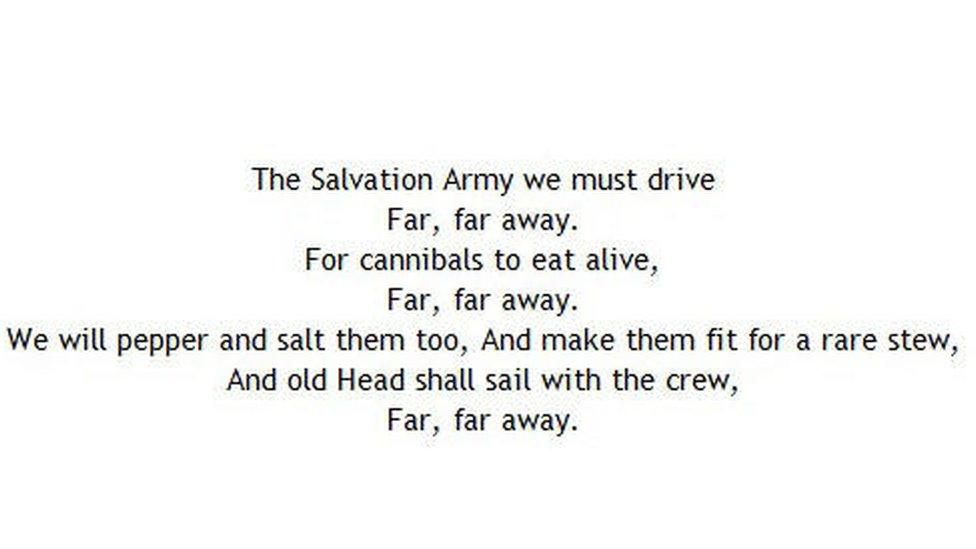

In response to the "soup, soap, salvation" slogan, Skeleton banners read "beef, beer and bacca". Makeshift uniforms were cobbled together by the Skeletons, and the Salvation bands were drowned out by a cacophony of whistles, horns and drums wielded by Skeletons, who sang their own songs, often with obscene or threatening lyrics.

The Skeletons sang their own songs, including this little ditty published in the Sussex Coast Mercury, 12 July 1884

Mr Wilson says: "Skeleton mobs would follow the Army, hurling paint-filled eggs, dead animals, burning coals and anything else available. When missiles were not to be found, fists, feet and sticks were used.

"The police would rarely intervene, and when they did, the Salvation Army's unpopular militant manner meant they were just as, if not more, likely to fall foul of their attention. Some in positions of authority, such as the mayor of Eastbourne, even joined brewers and other supporters by endorsing the actions of the Skeleton Army."

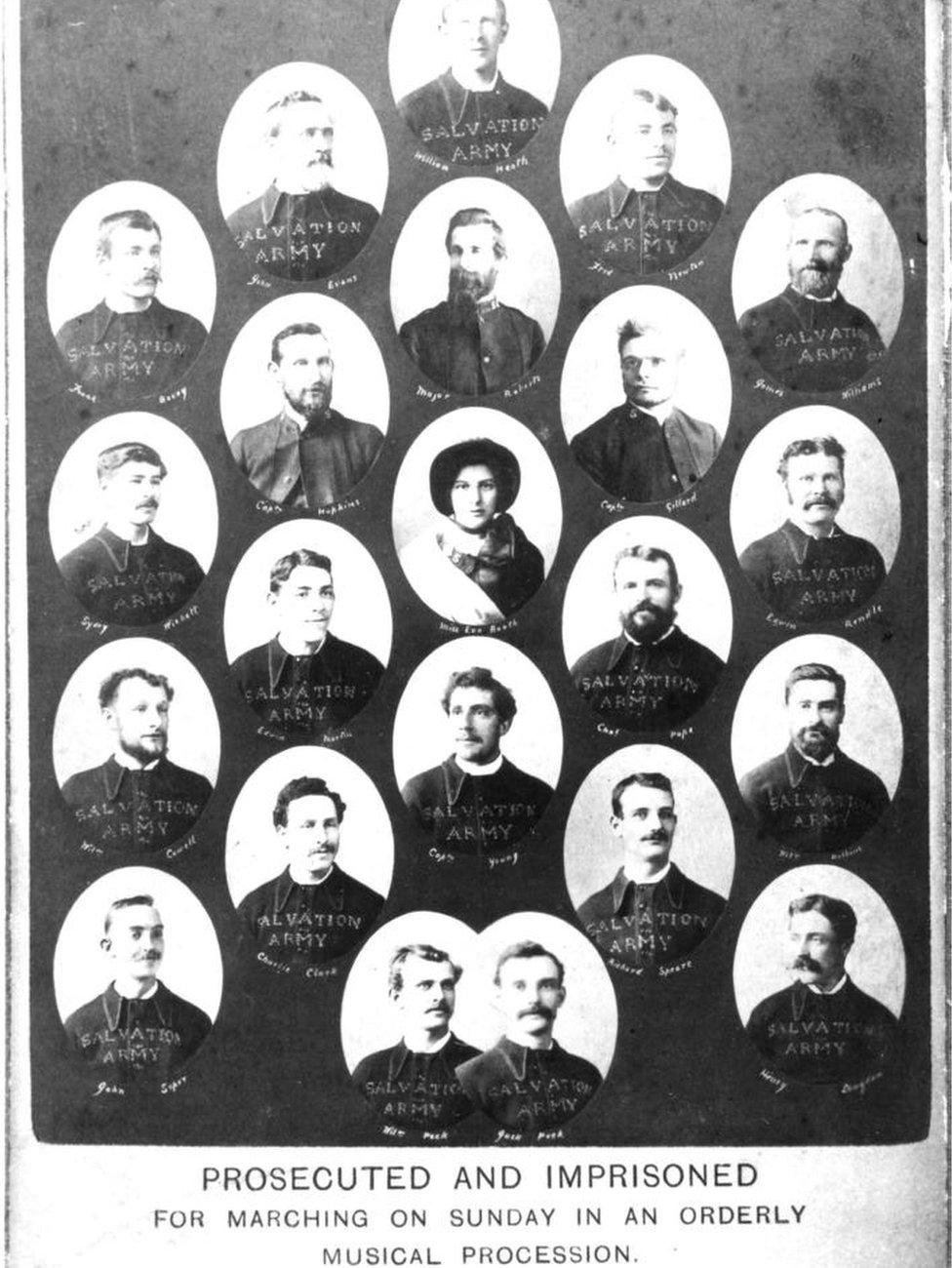

In Torquay, hundreds of Salvationists were assaulted, but the local council board responded by adding a clause - later repealed by Parliament - to the Torquay Harbour and District Act, to arrest and imprison Salvationists.

The board tried to ban "marching with music on a Sunday" on the grounds it attracted Skeleton troublemakers. But it was later ruled that a lawful activity (marching with music on a Sunday) was not made unlawful by the unlawful actions of others (Skeletons rioting).

In terms of freedom of expression, this principle is still the benchmark in constitutional law.

The publication Darkest England sought to appeal to those trapped in vice and poverty

Salvation Army archives show that the behaviour of the Skeletons towards Salvationists became increasingly severe.

According to Mr Hare, female Salvationists often suffered the most violent opposition and were frequently attacked, especially when in a leadership role. Male Salvationists were attacked but also ridiculed and jeered at for being "simple" and not being "proper men".

Riots broke out in Exeter, Worthing, Guildford and Hastings - where Susannah Beaty was killed.

The Skeletons were a manifestation of the earlier Bonfire Boys

During the late 1880s and early 1890s, thousands of Salvation Army officers were injured and hundreds of their buildings damaged. Mass brawls broke out in 67 towns and villages. Barely a week went by without a press report of an attack on Salvationists.

After a few tumultuous years, the early 1890s saw the anti-Salvationist frenzy die down. Police became more amenable to arresting the Skeletons, and the Salvation Army's right to promenade in public was enshrined in law.

There was no specific ending point to the Skeleton Army; it just faded away.

And the Salvation Army? It just kept marching on.