Liverpool FC star Craig Johnston: 'Jack Charlton said I was the worst player ever'

- Published

Craig Johnston remembers his time at Middlesbrough FC

He won the European Cup with Liverpool, scored in an FA Cup final and invented the biggest-selling football boot on the planet, but Craig Johnston's career started from humble beginnings - a coal shed in Middlesbrough.

Johnston overcame osteomyelitis - a bone infection - in his leg as a child. When he was a teenager, his parents sold their house in Newcastle, Australia, to pay for a plane ticket so he could pursue his footballing dream in England.

He said: "I went to Middlesbrough as a 15-year-old kid. It was 1975. Televisions were still black and white.

"I'd never been past Sydney and I was on my own. I got from London up to Middlesbrough and I didn't even have time to find the digs where the trialists stayed. I had to go straight to the game and I was already jetlagged.

"The day before, I was on Nobby's Beach, which is a beautiful sandy beach with aqua blue water and palm trees.

"Forty-eight hours later, I'm on Hutton Road. It was December, it was snowing and it was muddy."

Jack Charlton, pictured here with the Middlesbrough team in 1974 before Johnston arrived, was very much in charge

It was at this game that Johnston first met Middlesbrough boss Jack Charlton.

"I went on the field and within 30 seconds, I got slammed by this kid from Scotland who just took me out at the knees," he said. "I'd never felt so hurt or bruised in my life.

"I got up and tried to run around but every time I got the ball, I just lost it. I'd never felt so humiliated in my life… until I went into the dressing room.

"Jack Charlton came in at half-time and we were getting beat 3-0. He was red with rage. Managers weren't even supposed to be at trial matches.

"He had a go at everyone. He went around the room and said 'you're useless, you're rubbish, you're hopeless'. Then he got to me.

"He asked me where I'm from and I said 'I'm from Newcastle, Northern New South Wales, Australia'.

"Charlton replied: 'Well, you are the worst footballer I have ever seen in my life. You won't make a player while your arse still points to the ground. Now hop it.' But he didn't say hop it.

"Everyone was stunned and horrified, including me."

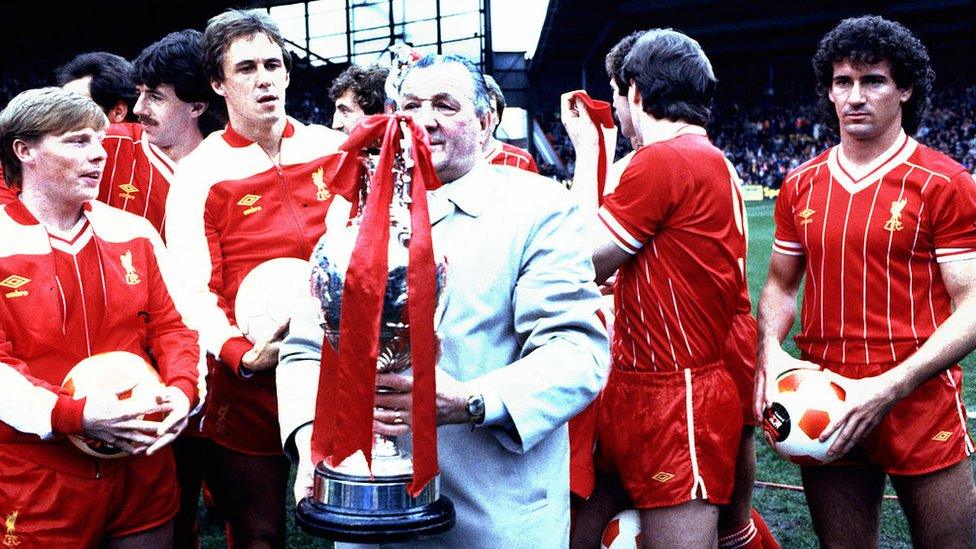

Johnston's career thrived at Liverpool, winning the First Division trophy in 1983

Matters were about to get worse when Johnston headed over to the Medhurst Hotel on The Avenue, where the trialists stayed.

"There was a lady called Nina Postgate who ran it," he told the BBC Radio Tees Sport Boro Podcast.

"In my tears, I explained to Nina that I'd been told to hop it.

"She said: 'I'm sorry, you can't stay here. This is the official digs for the trialists and people who make it. I might lose my job.'

Nina then made him some beans on toast and a cup of tea.

"My journey as a 15-year-old going over to Middlesbrough and the four years I had there possibly could have been the best and most soulful time of my life."

"She said: 'There's an old coal shed out the back but it's been cleaned out. It's got a radiator and you can stay there overnight but don't say anything.'"

The teenager settled into his new environment for the night, wiped away the tears and thought about how he could turn his fortunes around.

"The truth of my story was that Jack Charlton was 100% right," he said.

"I couldn't control the ball, I couldn't pass, I couldn't shoot. I just couldn't play.

"I had that realisation in the next couple of days and I was fortunate that Nina was hiding me from everybody. She gave me valuable time to think about how I was going to solve the problem.

"I ended up staying for at least two or three weeks in the coal shed. Maybe it was a month. My parents weren't very wealthy and it was a one-way trip. So I couldn't go home either."

Boro fans in jubilant mood before an FA Cup match at Ayresome Park in 1978

Johnston began to practise alone in a car park close to Middlesbrough's former home, Ayresome Park, using obstacles made out of bins and chalk markings on the wall.

Boro player Graeme Souness noticed him training, and brought him into the Medhurst.

"He was captain at the time and he'd heard about the roasting I'd got," Johnston said. "The players gave me a couple of nicknames like Skippy and Roo.

"They then asked me to clean their cars, which I gladly did, and I cleaned their boots because they knew I needed money to get home.

"I loved it because I thought I was part of the group even though I wasn't allowed to train and the club wasn't allowed to know I was there."

Johnston meets an inspiration for his nickname in 1991

Johnston continued to spend hours in the car park working on his skills after a day of secretive chores for the squad.

He also played football with local children on Ayresome Park Road in the town centre.

"It backed on to the old general hospital. The wall I used to kick the ball against was a mortuary.

"I'm up until 10pm at night training and sometimes I'd have to go into the mortuary and get the ball back.

"It wasn't a place you wanted to be in as a 15-year-old so I learned to get my head over the ball. That was my motivation.

"I drew a real size goal with four targets, five targets if you include the goalkeeper. I set myself goals every day to beat and I was allowed to go home once I'd hit them.

"This was crucial to me because if I had hit my targets quickly, then I could go into the Medhurst and have beans on toast with the players.

Johnston now works as a photographer

"I realised that I could be a better player than when I woke up in the morning. This is what made me a professional player.

"I would watch the kids for months from afar once I'd finished all my chores and I noticed there were some really good players.

"One of them came over to me and asked me who I was because I had a Middlesbrough tracksuit on, and I explained I was the cleaner.

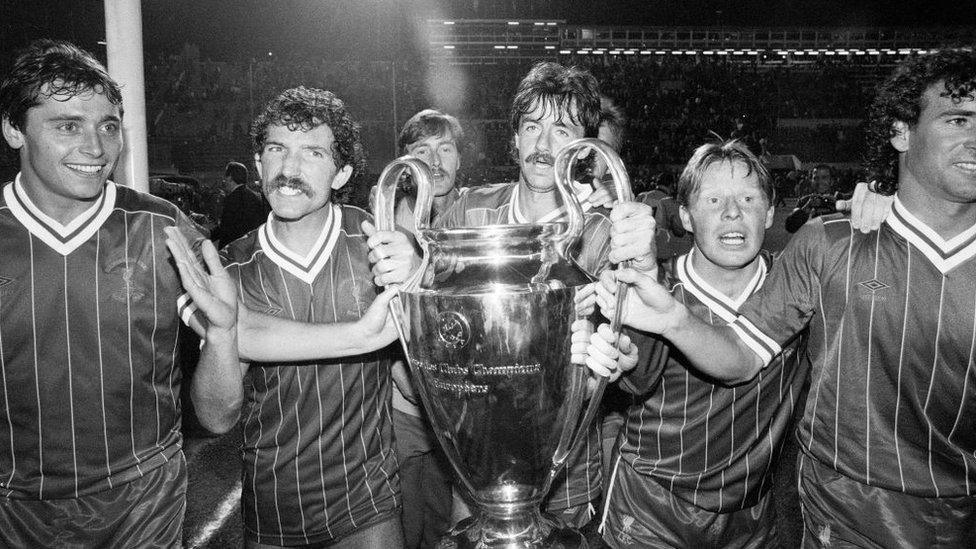

Johnston (right) with Michael Robinson, Souness, Mark Lawrenson and Sammy Lee after winning the 1984 European Cup

"They asked me to play but I was so embarrassingly bad that they started taking the mickey out of me and they called me Skippy the bush kangaroo and sang that song! Of all my memories, those are probably the finest."

Middlesbrough eventually signed him in 1977 and he made his debut for the club in a 3-2 FA Cup win against Everton in January 1978, becoming one of their youngest ever players, external at 17 years and 51 days.

"When I made my debut, I played well and I was coming off the field and getting a few high fives from the lads," he said.

"A bunch of kids ran on to the field and started hugging me and saying: 'Go on Skippy! Go on Roo!'

"It was the kids from Ayresome Park Road. Somewhere a photographer took a picture of those kids and that's what I treasure dearly."

Johnston is back in Australia where the weather in Sydney is slightly better

Johnston would eventually go on to make 64 appearances for Middlesbrough, scoring 16 goals, before moving to Liverpool in 1981 and winning five league titles.

He would also lift the FA Cup in 1986, scoring in the final and beating Merseyside rivals Everton 3-1.

"Stepping out on Wembley was horrifyingly scary," he said.

"[Jan] Molby skewed the ball across the front of goal and Kenny [Dalglish] missed it. It came to me and the goalkeeper was off his line.

"Everything slowed down. But when the goal went in, I jumped up in the air and shouted 'I've done it! I've done it!'

"I didn't mean I'd scored a goal. I meant that I'd got through the hospitalisation, I took my parents' sacrifice and made it work, I took Jack Charlton's dismissal on the chin and figured out how to get out of the coal shed.

"I got to be in the best team in the world on that Saturday afternoon. I could've honestly died on that spot that afternoon and I'd have died a happy man."

Johnston scored the second goal against Everton in the 1986 FA Cup Final

After retiring at the age of 27 to look after his ill sister, Johnston's new journey would see him design what he calls "the largest-selling soccer shoe of all time" - the Adidas Predator.

"I developed it. I patented it. I trademarked it and spent five years on it. Adidas actually knocked it back.

"The fundamental underpinning behind the boot was: What part of the boot, on what part of the ball, to what effect. So it was all that work I'd done in the Middlesbrough car park that got the patent.

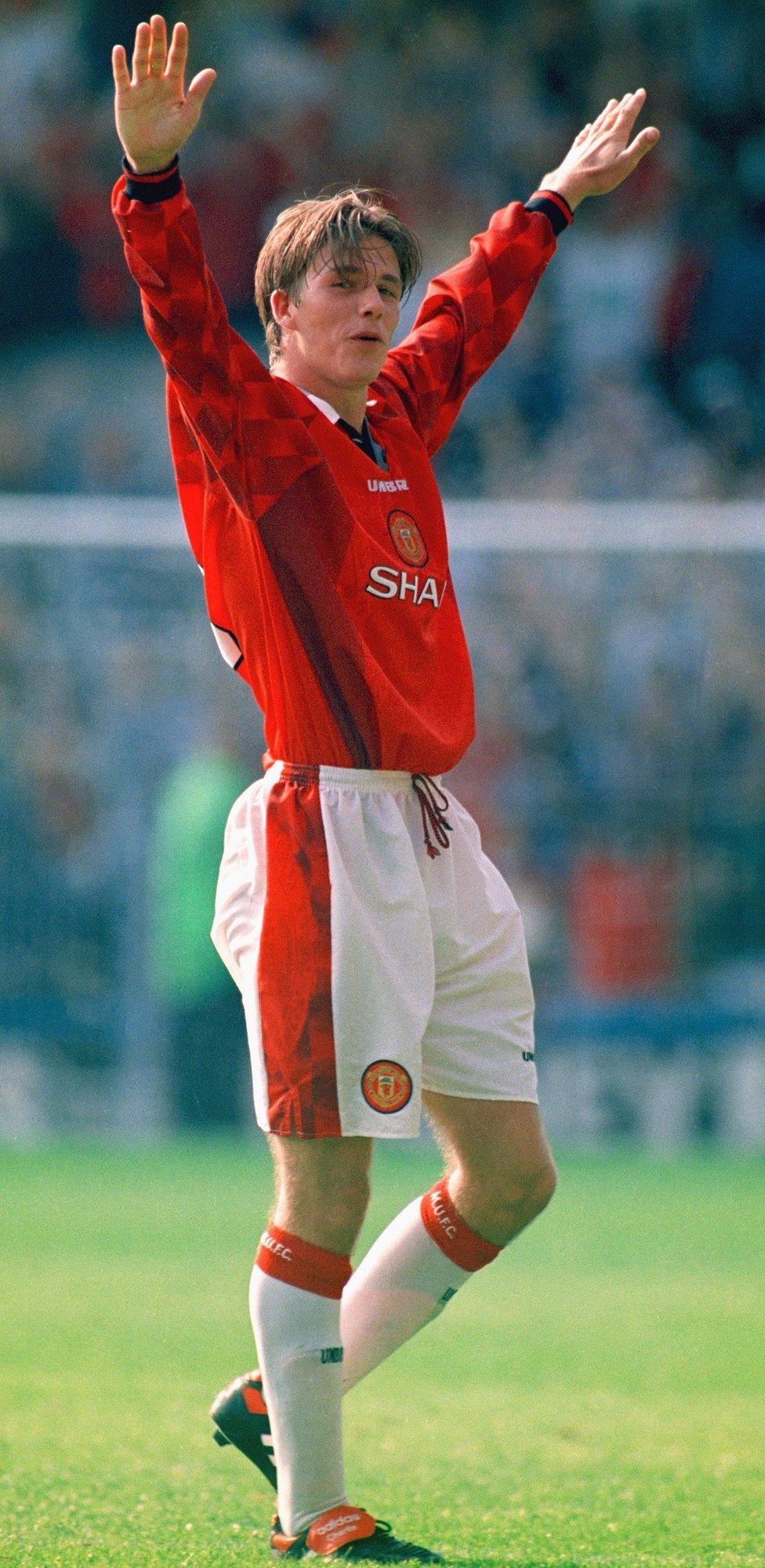

"I handmade the David Beckham prototype and took it to him. He scored from the halfway line on the first game against Wimbledon [in 1996].

"I figured out how to get it in front of players. I presented it to [Zinedine] Zidane and [Alessandro] Del Piero too."

David Beckham celebrates in his boots after scoring from the halfway line on 17 August 1996

When asked if he'd paid his parents back through the career he had, he answered tearfully: "You can never pay them back.

"My journey as a 15-year-old going over to Middlesbrough and the four years I had there possibly could have been the best and most soulful time of my life, even though they were incredibly tough.

"There's something very raw and honest about Middlesbrough people which I'll never ever forget. They always come up to me in the street all over the world. The moment I hear the accent, it makes me laugh and it makes me proud that I lived there for so long."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published31 January 2020