Covid: Front-line workers reflect on the last year

- Published

Paramedic Pennie Boler said the public's support meant a lot

Front-line workers in the north-east of England say a year of dealing with the Covid pandemic has put them under huge strain as they have had to adapt to new ways of working.

On the first anniversary of the UK going into lockdown, a paramedic, junior doctor, senior nurse, call handler and a chaplain reflect on the experiences of the last year and how they are hopeful for the future.

'I remember driving in complete silence'

Paramedic Pennie Boler, 29, has mixed feelings about the last year. She has found it very stressful, but also "good" thanks to the support of the general public.

She said: "We've had loads of support and thanks from the public, they've been really generous, we didn't expect it. It wasn't really necessary, but really nice. The thanks goes a long way even though we are just doing our job.

"It's been hard and unpredictable, but really shown us how the public feel about us."

Pennie will never forget being called out to her first Covid-positive patient last March.

She recalls: "I remember driving to the job in complete silence with my crew mate. Usually we'd be chatting en route, but this was just like an eerie silence.

"When we got to the scene I remember going to the back of the vehicle and putting on all the PPE; face mask and full white suit, double gloves, things we'd never used before.

"I remember going in alone so only one of us would be exposed to the virus. I remember listening to the patient's chest and my heart was beating far faster than theirs. I was so nervous, thinking potentially I could contract the virus."

Pennie said that patient made a full recovery at home and after that case she "calmed right down" and learned what to expect.

She and her colleagues dealt with many patients who were struggling to breathe with the virus. They helped relax them and check their oxygen levels.

But not all patients recovered at home and the sickest were transferred to hospital.

She said: "You would get them to hospital knowing potentially there was no cure. You were taking patients out of their family home. You knew that potentially they would never see their family again.

"It was very difficult shutting the ambulance door on a family member knowing that could be the last time they see a loved one.

"I'm a very 'huggie' person. I'm a professional, but also a human being and I like to give out hugs to family members, but we had to keep our distance."

She also said there were times she did not want to go into work, but the clapping for the NHS and posters in windows kept her going.

She added: "All front-line staff just clung together. Some days you could have a run of jobs that were just Covid, Covid, Covid.

"Then you could be dealing with a birth, or cardiac arrest, then back to Covid patients. So we were seeing everyone else, not just Covid."

'I'd be lying if I said I hadn't cracked at points'

Louis Ttofa-Roberts said patients were terrified and, to an extent, so were staff

Louis Ttofa-Roberts, is a foundation year two doctor in ITU and anaesthetics at North Tees Hospital in Stockton. He only began working in August 2019 and recalls how, by the following year, it was all very different.

Having to wear full PPE all day and deal with a virus no-one had ever dealt with, he said he found it difficult to interact with patients as they were not able to see a comforting smile.

"The patients weren't able to see their relatives, so they were terrified and to an extent we were pretty terrified in the beginning.

"We are quite used to dealing with people coming into hospital who are at the end of their life, but they did not have their loves ones with them.

"So a lot of the time we, the staff, were spending their last moments with them.

"You carry on doing your job, but when you step out of it it's really tough and you ask 'what was that day?'"

Louis said work got a lot easier by the summer of 2020 when cases started to fall. But he said when the second wave hit in October he too was "terrified."

He explains: "By that point we knew what we were dealing with. However, we knew a little bit more about the disease and possible treatments. Also we had an inkling the vaccine was coming. But that bit of adrenaline that was there at the start wasn't there anymore.

"Quite frankly everyone at the hospital was pretty gutted and downtrodden because we knew it was going to get worse."

He remembers how things did get worse over Christmas and "spirits slipped", not just within hospitals but across the "whole country", with many younger people who did not have underlying health conditions being admitted with the virus during the second wave.

He said: "To see their oxygen requirements increase and for them to require invasive ventilation, I can remember this real confusion of what was going on because the virus often presented like a few other illnesses."

Having to tell families that a loved one was minutes from death took a "terrible mental toll" and was all the more difficult because they had not seen them since they were admitted.

"It was the volume of these conversations that was tough, often two or three times a day.

"There's only so much plodding on and cracking on you can do and I'd be lying if I said I hadn't cracked at points.

"But I now feel that people are starting to feel a bit brighter - starting to see the light as the case numbers go down.

"I think that it's important that people at home carry on with all their hard work. Keep washing your hands and sticking to the guidelines and if you are offered the vaccine, take it up."

'It's been difficult but we pulled together'

Jenny Cain said the second wave was "pretty horrendous"

Jenny Cain is a senior sister at Newcastle's Royal Victoria Infirmary and said the second wave was much harder than the first for her and her team.

"As time went on it became more fraught. The second wave around Christmas time until fairly recently was pretty horrendous.

"We had a lot of patients in and the sheer volume of patients was just massive."

She said the last year had been difficult and had taken a real toll.

"It's been difficult for us all but I think we have pulled together. My team have been fantastic.

"When you come every day and you're donning and doffing the PPE it's exhausting. It's hot, it's tiring, it's just emotionally and physically draining."

The hospital's last Covid ward is being wound down now and she said she was hopeful it was coming to an end.

"It just feels great. I can see light at the end of the tunnel. It feels happy. The morale has lifted on the ward.

"It's just so good to see so many fewer Covid patients coming through the door."

'Nobody wants to die alone'

Jordan Brown "never got a break" from the word "Covid"

Jordan Brown is a health advisor for 999 and 111, dealing with calls from the public.

He remembers that when coronavirus hit the news, especially with cases confirmed in China, people were calling in a "panic", asking if the virus "was here yet", what they could do and how to protect others.

He said: "It was hard because of the mass of people calling. There were those few people who had actually been to China within the time frame and that was daunting, speaking to someone who may have been exposed to the virus.

"The pressure of call after call, every single call was Covid-related. You never got a break from the word, it was very mentally challenging. Even if people didn't have any symptoms there was always a fear of the virus."

Jordan recalls dealing with distressed callers when the virus hit the UK.

"It was awful, listening to people who were alone and struggling to breathe with underlying health conditions.

"We were reassuring them, saying we were there to help and were going to get the ambulance to them as quickly as we can. Giving them care and guidance over the phone, asking if they had inhalers to help them.

"We often didn't know if it was Covid and you could just feel the fear through the call."

Jordan said dealing with calls was "terrifying" because people were worried they were going to die.

"Advising scared family members they could not go with their loved ones in a critical condition was hard.

"People were thinking 'am I going to die when I get to hospital?' It just got worse day by day, calls were starting to heighten when patients were becoming more and more unwell, then having the conversation that they needed to go alone."

Jordan's worst experience was talking to a patient with breathing difficulties, arranging a crew to go out only for them to get the address and find no answer at the door.

He said the fire service had to break into the property, but the patient had already died.

He said: "That patient died alone. Covid has taken the lives of so many people who were alone. Nobody ever wants to die alone, but dying in that way with breathing difficulties is terrifying.

"I can imagine our crews are exhausted. It's a lot of work on a daily basis without Covid. Hearing the number of deaths every day and thinking 'I probably spoke to their family'."

'The healing must take place'

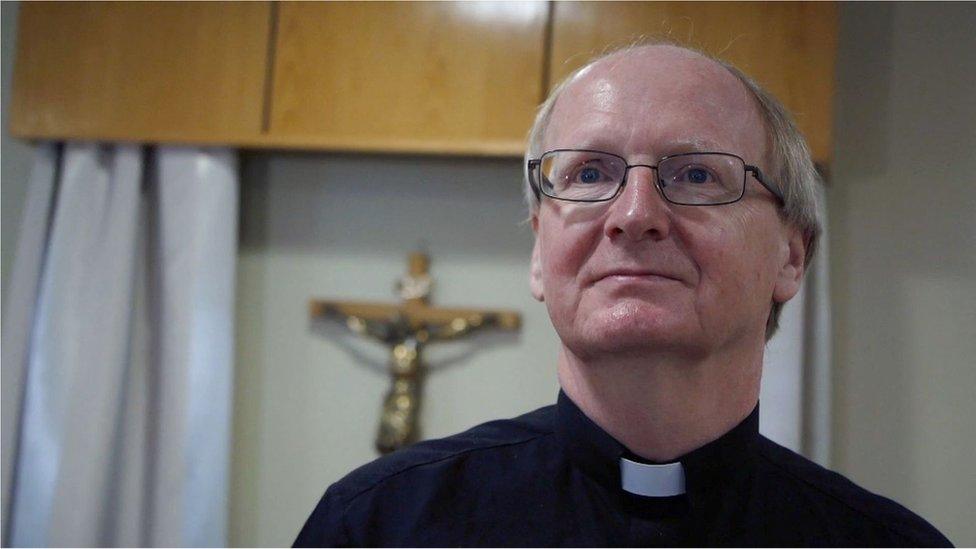

Chris Clinch believes a healing process will lead to a better society

Chris Clinch is a chaplain for Northumbria Healthcare Trust. He described this year as being "very different from anything we had ever experience before".

He and his colleagues have supported families when relatives' life support systems have been turned off, or they were given the news that they were not going to survive.

"But sometimes it can just be about long conversations with people who are trying to cope with the loneliness that Covid has brought or the failure to be able to live their normal lives, which had been so important for people", he said.

Many people had come into hospital scared and unsure about what was going to happen to them and that fear made people react in different ways, including feeling that they could not cope. He said the main approach had been to listen.

As well as the impact on patients and their families, Mr Clinch said hospital staff had been hit hard.

"It's an enormous toll and a lot of our staff are very young, they have never experienced this before, they may have not been in nursing or healthcare for very long.

"It can be quite a shock to come across death anyway in the numbers we've been having. And to see patients suffering in a particularly difficult way, this has led to us having to be part of a support mechanism within the hospital."

He believes there is hope now thanks to vaccines and people will be able to see some more normality soon. Crucially, they will have human contact again.

"I think it's been a year that none of us will forget and I can only hope that we will grow through it and not just see it as a year of darkness, which it has been for many people.

"But as time goes on the healing must take place. Healing in all senses of the word, in a truly holistic way, will help bring something good out of what has happened and we will be better people and a better society because of it in the end."