Drugs county lines fight 'to last a generation'

- Published

County line gangs are urban drug dealers who sell to customers in more rural areas using dedicated phone lines

The fight against gangs exploiting children to deal drugs is likely to last a generation, a senior police leader has said.

Assistant Chief Constable Jackie Sebire, the National Police Chiefs' Council's lead for serious violence, said it was "all I think about".

The warning comes after a week of raids across the country to disrupt so-called county lines gangs, in which more 1,000 people were arrested and almost 300 weapons were seized.

"This is going to go on for a generation," said ACC Sebire. "It frustrates me... It does really worry me."

ACC Sebire is a former Scotland Yard detective with more than 25 years' experience

County lines is a term used to describe criminal gangs who move illegal drugs from big cities to smaller towns and sell them using dedicated mobile phone lines.

The latest figures suggest there are 600 potential county lines, which is a reduction due to more accurate recording methods and improved police activity.

The gangs often recruit vulnerable children to carry and deal Class A substances, to reduce their own risk of arrest.

ACC Sebire said organised crime groups, and the violence that comes with them, were "expanding outwards" into smaller towns and rural areas.

The senior officer said there was evidence of gangs in areas such as Luton adapting their "business model" to run drug lines out to Peterborough and Milton Keynes.

Almost 200 officers from Thames Valley Police carried out raids across Banbury, Witney, Oxford, Milton Keynes and Swindon and arrested 13 people on Wednesday

Jacob's story

A textbook example of how county lines gangs can ruin lives is the case of Jacob, a 16-year-old boy from Banbury in Oxfordshire, who was targeted by adult criminals from July 2017 until his death in April 2019.

Jacob's mum, Karla, told the BBC how her son was was groomed and manipulated into a world of drug trafficking and violence at the age of just 14.

Karla said her son's personality "literally changed overnight" when they moved to Banbury from the north east of England and Jacob started socialising with a "new group of friends".

"At first you think it's just teenagers," she said. "Then Jacob started going missing, and hanging around with children that were a lot older, well, young adults basically."

"I really don't think he realised how dangerous it was at first... he was groomed" - Karla, Jacob's mum

Jacob was recruited as a dealer, picking up drugs from couriers sent from London to Banbury train station.

Karla recalled finding "hundreds of these little plastic bags" containing drugs in Jacob's bedroom. She fought a losing battle to keep him at home.

"I tried locking the doors, bolting the front door. He got out of windows. It didn't matter what I said or did," she said.

"You just literally feel like there's nothing you can do. People would say 'well, if he was my boy I'd do this or I'd do that.' Believe me, I tried it all - everything."

Over 21 months Jacob was reported missing more than 20 times and was recorded in 26 police reports, mostly for violent crimes, including assaults against his mother.

But he was never brought before the courts or convicted, often due to a lack of evidence or victims not wishing to press charges.

Karla believes her son was exploited by criminals because he was so young and "the fact he wasn't in school" for two years. He was rejected by four educational settings due to his "perceived behaviours and risks to other students".

She said the way the gang members, who have never been identified, groomed her son was "child abuse".

A serious case review published earlier this year found major failings by the police and local authorities in Oxfordshire.

Jacob was "coerced and controlled" into committing crimes from his teenage years

It included one glaring fact, that Jacob had not been enrolled in a school or provided any type of education for 21 months, which was found to have left him "highly vulnerable" to being exploited.

Karla said she didn't think there was "any one person to blame" for her son's death, but believed it could have "definitely" been avoided, and said his lack of education was a big factor.

"I think that was a massive, massive factor and feeling like everybody's turned their back on you," she said.

"I never got a chance to have that conversation with Jacob. But did he kind of feel like well, this is all I've got now?

"You know, the schools don't want me. My mother's relationship's pretty poor... the police don't like me."

From October 2018, it was thought that Jacob started to get into debt and was now using drugs and alcohol as the violence intensified.

In April 2019, Karla found her 16-year-old son dead in his bedroom. A coroner concluded Jacob was "intoxicated and distressed" when he died but found "insufficient evidence" that he had intended to kill himself.

"It's horrible to see your family just in absolute bits," she said.

"We will never be the same again. Never."

Karla said her son was a "great kid" who was an "absolute ball of energy"

Sadly Jacob's story is not a one off, with county lines drug dealing now spread across the UK.

The Office for National Statistics estimated that more than 28,000 children were in street gangs in England and Wales between March 2016-18.

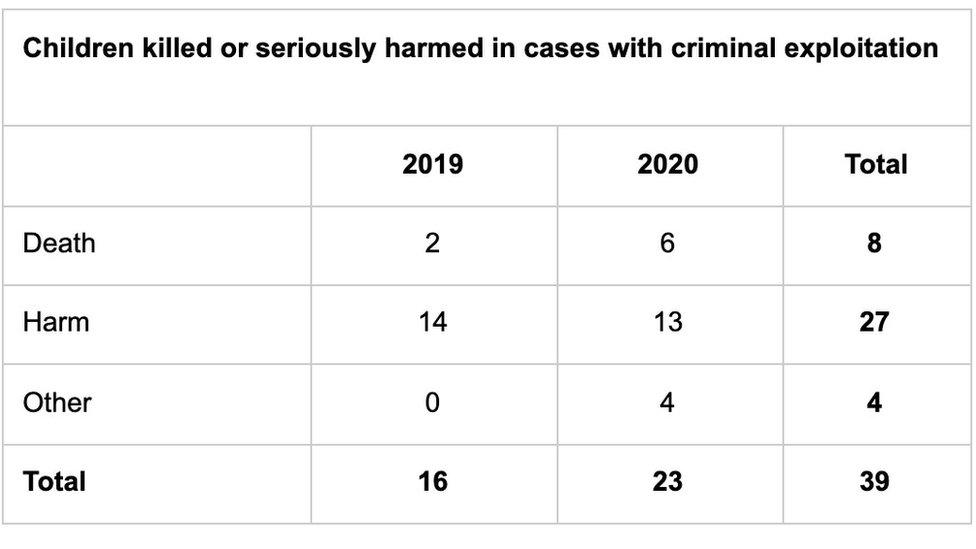

According to figures obtained by the BBC through a freedom of information request, 39 children were killed or harmed in England in cases with criminal exploitation during the calendar years 2019 and 2020.

The current data does not appear to show the extent of child criminal exploitation

Source: Freedom of Information request to the Department for Education

However, those figures don't appear to capture the full extent of the problem, as in 2020 alone 1,544 referrals were made to the government's National Referral Mechanism where children were flagged as possible victims of county lines.

Mark Russell, chief executive of The Children's Society, said exploited children need to be "seen and treated as victims and offered protection as early as possible".

"This is not yet the case for many children as they are seen as criminals and struggle to receive vital support," he said.

Mr Russell added children in similar circumstances to Jacob were not being identified until the exploitation was "deeply embedded, leaving them traumatised and in fear for their lives or those close to them".

'Data desert'

There are also concerns that the battle against the criminal exploitation of children is being undermined by a lack of data.

"County lines is a data desert," says Joe Caluori, head of research and policy at criminal justice think tank Crest Advisory.

"Few public bodies have ever published data on cohorts of young people in a way that would help us understand risk factors."

Iryna Pona, policy manager at The Children's Society, said the lack of data "hampers the fight against child criminal exploitation".

She said it contributed to "a postcode lottery in the support available across the country".

In a recent study the charity found only half of councils recorded data on children identified as being criminally exploited, and just one in five said they could retrieve and share this data.

A large quantity of Class A drugs, money and weapons were seized in recent raids in Oxfordshire

The National County Lines Co-ordination Centre, set up in 2018, aims to improve intelligence gathering to ensure potential victims are protected.

But despite a lot of good work by police and their partners, the system of safeguarding too often fails because agencies are still too disjointed, a theme which is common through Jacob's and other victims' cases.

The police rely on data from crime records, from hospitals and schools, to build a picture and about half of forces use a "vulnerability assessment tool" to identify those who are susceptible to criminal exploitation.

But, according to ACC Sebire, a lot of the exploitation of children to deal drugs "really is hidden".

"We don't really understand the lived experience of these kids and what they're going through until it's almost too late," she added.

"These young people are growing up in areas of deprivation with all sorts of challenges, let alone the exploitation issues, and you do wonder where their opportunities to turn their lives around are going to come.

"I'm not sure we know how to fix it yet."

Related topics

- Published27 May 2021

- Published14 May 2021

- Published6 February 2021

- Published19 January 2021