Covid: Things are looking up in Bolton, eye of the variant storm

- Published

The Army lent its medics to help with vaccinations

Four weeks ago, Bolton was described as "ground zero" of the Delta coronavirus variant in the UK. A month later cases are down by 30%. So how did they do it?

As children prepared to go back to school after the Easter holidays, something worrying was happening in Bolton, Greater Manchester.

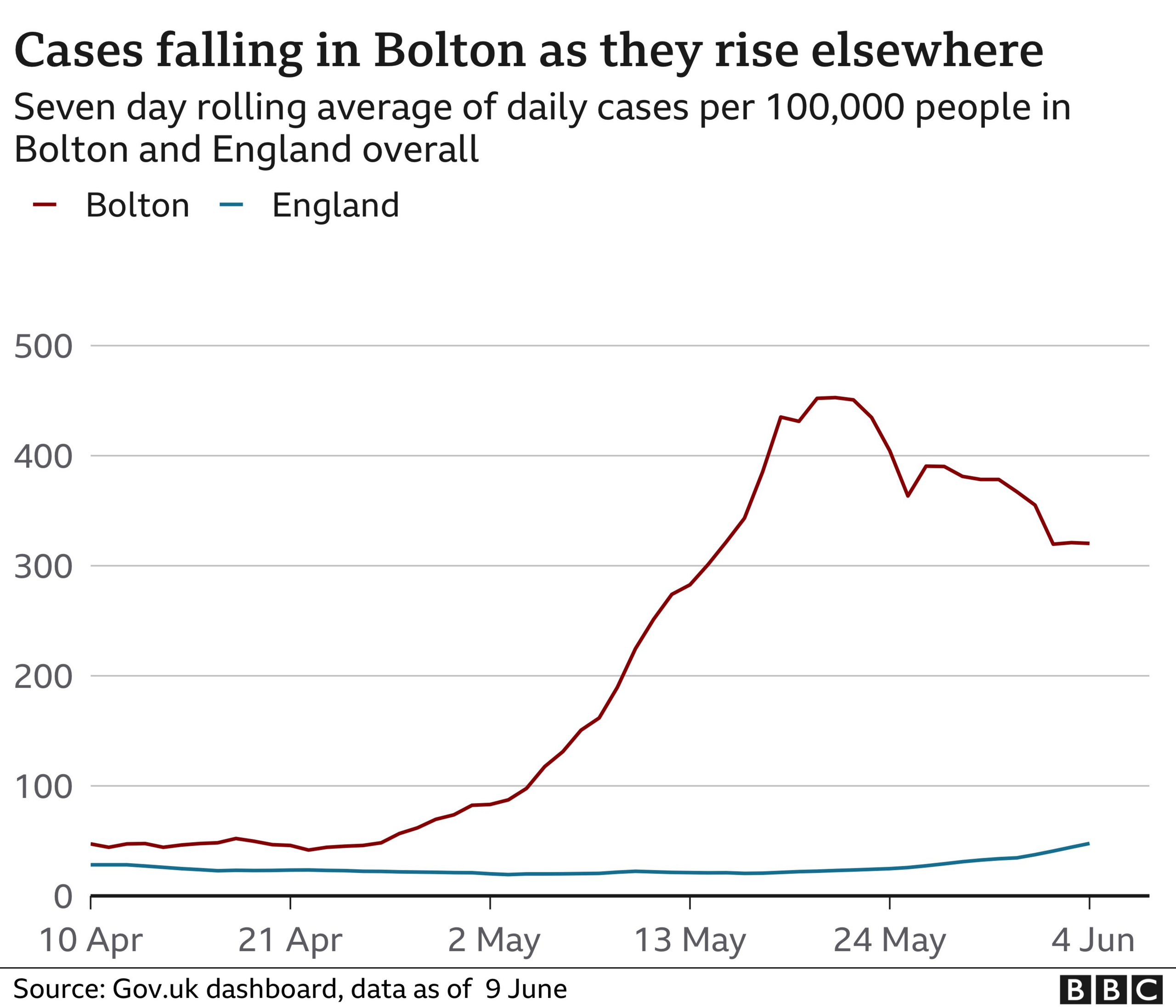

Daily cases of coronavirus, which had been squashed to near single figures by lockdown restrictions, were starting to rise, doubling in the last week of April and again in the first week of May.

A local newspaper reported, external three cases of a new variant of the virus had been detected in the town. The variant, first found in India, has since been classed as 40% more transmissible than the previously dominant form of the virus.

In the third week of May, Bolton recorded 453 cases per 100,000 people, higher than at any point in January and similar to levels seen last autumn.

The town became the focus of national attention, as the emerging variant began to threaten the UK's unlocking schedule.

About half of all new infections were being detected in just three neighbourhoods - Rumworth, Deane and Great Lever. They have a young population, with a university campus and community college. They are poorer than average, with higher levels of dense social housing.

The local public health team had, in fact, just put in place a strategy to counter a different variant, first detected in South Africa.

It put the town "on the front foot," says Lynn Donkin, Bolton's assistant director of public health, whose team had already hatched a plan to surge test in those areas. The idea had been to flood those neighbourhoods with Covid tests to try and detect people with mild or no Covid symptoms. Mobile units were sent in and teams of staff and volunteers went door-to-door alongside 50 troops from the 1st Regiment Royal Horse Artillery.

"Residents got a knock on the door and were taught how to use a PCR test," Ms Donkin says. "We returned a couple of hours later to pick it up. This way had a really high return rate."

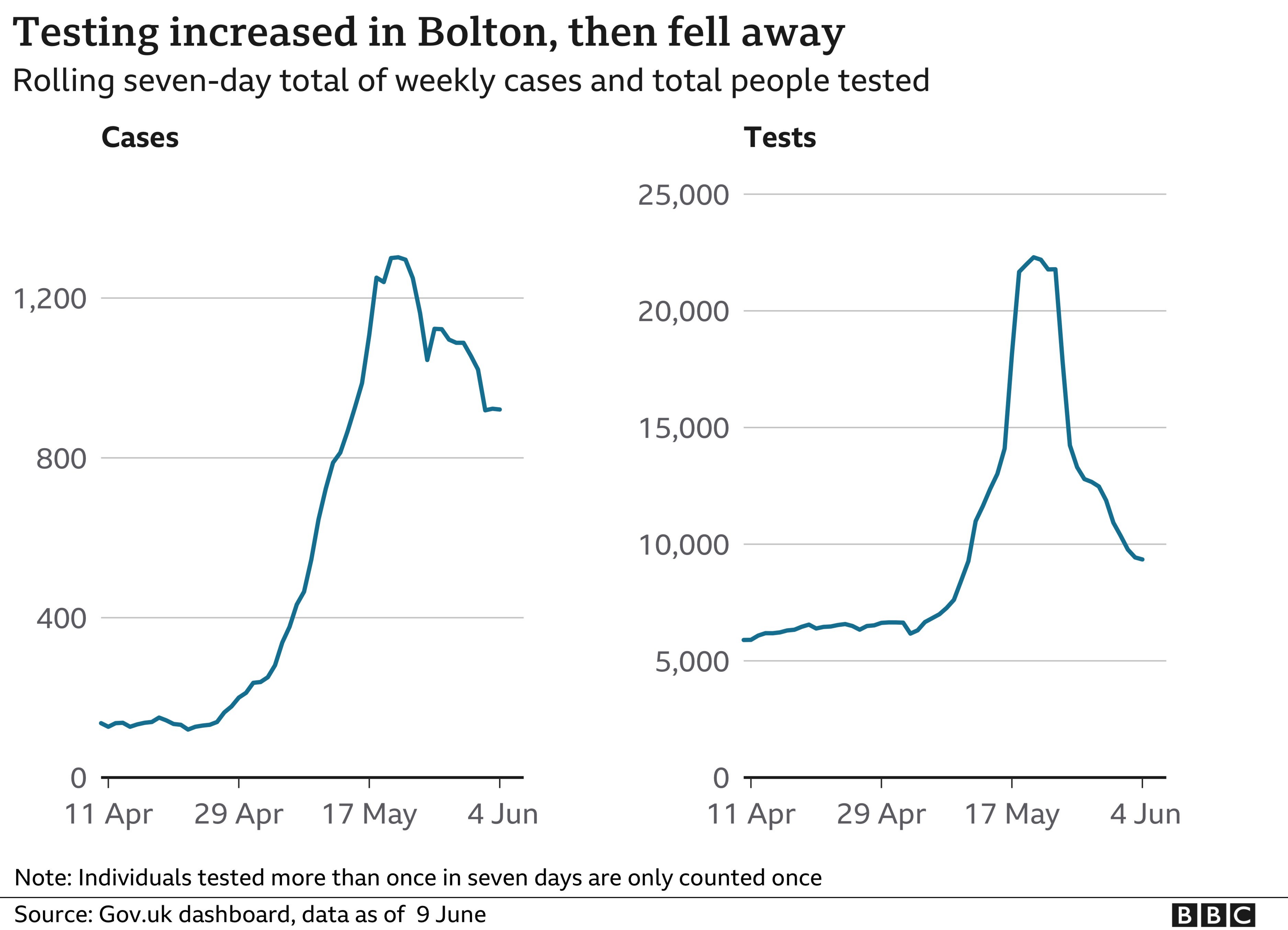

In May, 155,016 Covid tests were carried out in Bolton - one test for every two people living in the town.

The results showed the virus was spreading much faster in younger age groups.

In the week to 22 May, 10-14 year olds in Bolton were recording infection rates of 1,272 per 100,000 - more than double the rate of those aged 45-49.

Local schools were forced to close whole year groups with pupils returning to online lessons. However, Ms Dorkin says it was an "oversimplification" to say children were driving the spike.

Long queues

At the modern Essa Academy south-west of the town centre, pupils were asked to continue wearing masks, while twice-weekly testing of children, which had been parents' responsibility, was brought back into the school to boost uptake.

It meant a 96% take up, says the headteacher Martin Knowles.

The school also became part of a vaccination drive in the town. Its car park hosted a giant white vaccination bus. Long queues started snaking around the block. Locals set up stalls offering free water and snacks to those waiting in line.

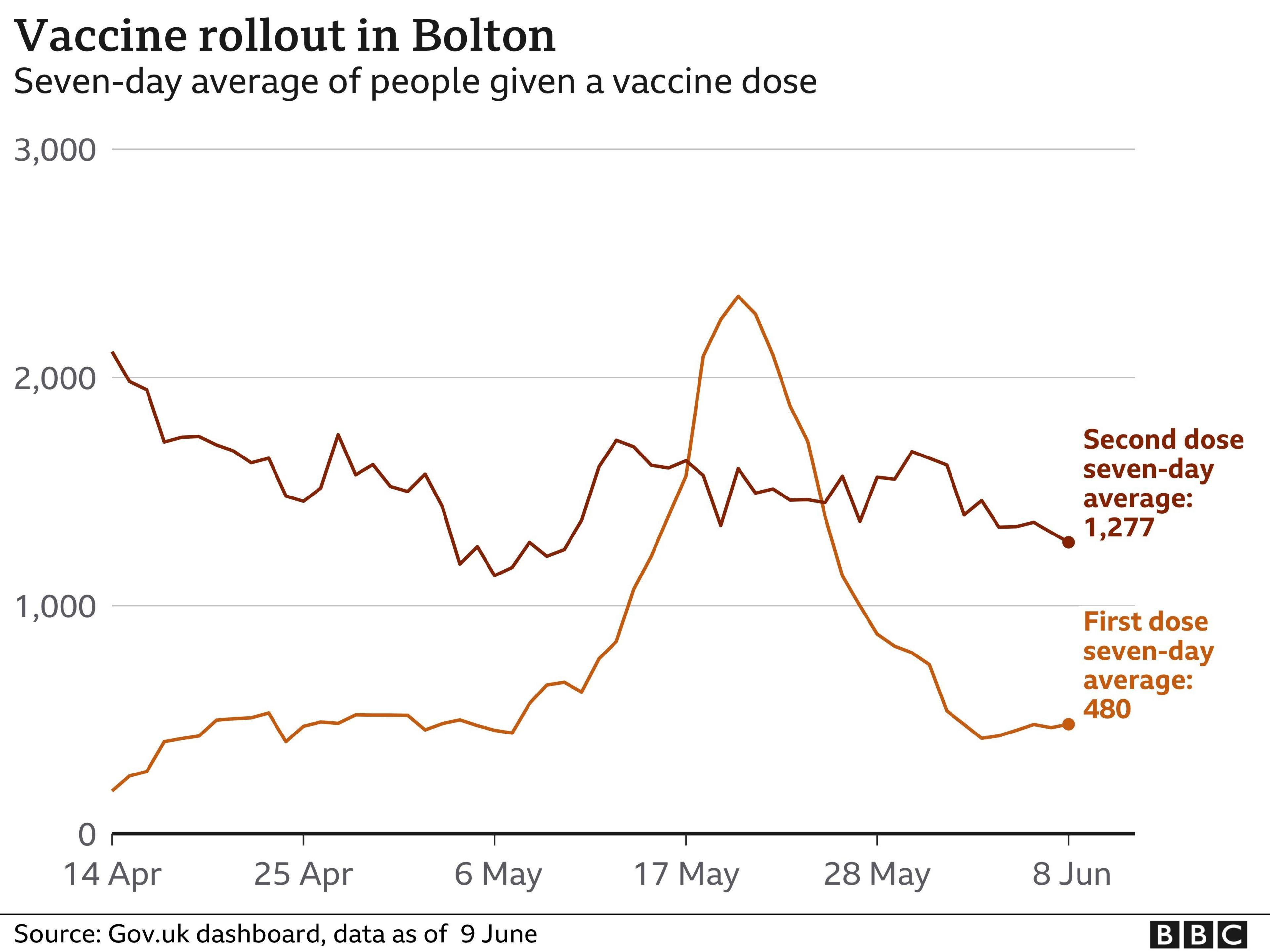

Over a single weekend in May, an extra 6,200 people were jabbed at that site alone.

Combat medics, from Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps, at a rapid vaccination centre

The plan was to drive down infections by reaching members of the public who had not yet taken up the offer of a jab.

Queues formed early that Saturday morning, recalls Dr Helen Wall, responsible for Bolton's vaccine programme. "There were some who had clearly been eligible for a vaccine for some time who had finally decided to come forward."

Seeing the response, as well as the small army of volunteers, proved an emotional moment. "I stood and cried at the side of one of the tents. It was a massive call to arms," she says.

In the line were large numbers of younger people who, at that point, might have thought they didn't qualify for a vaccine.

Some were turned away. But officials say they looked for reasons - such as people having an underlying health condition or helping to care for an elderly relative - to give a jab under government guidelines, rather than exclude them.

The vaccine bus and other pop-up sites like it have jabbed an extra 22,000 people in Bolton since 7 May, alongside 80,000 doses given at doctors' surgeries and pharmacies.

But officials believe the publicity might have helped achieve something harder to measure - a subtle shift in behaviour as people became more aware of the risk of the new variant.

"You were driving down streets seeing volunteers and the Army," says Dr Wall. "It was a presence people just couldn't ignore."

By the start of June, it was clear something was working - the number of new cases in Bolton had started to decline. Part of that is likely down to a reduction in local surge testing - fewer tests mean fewer people testing positive.

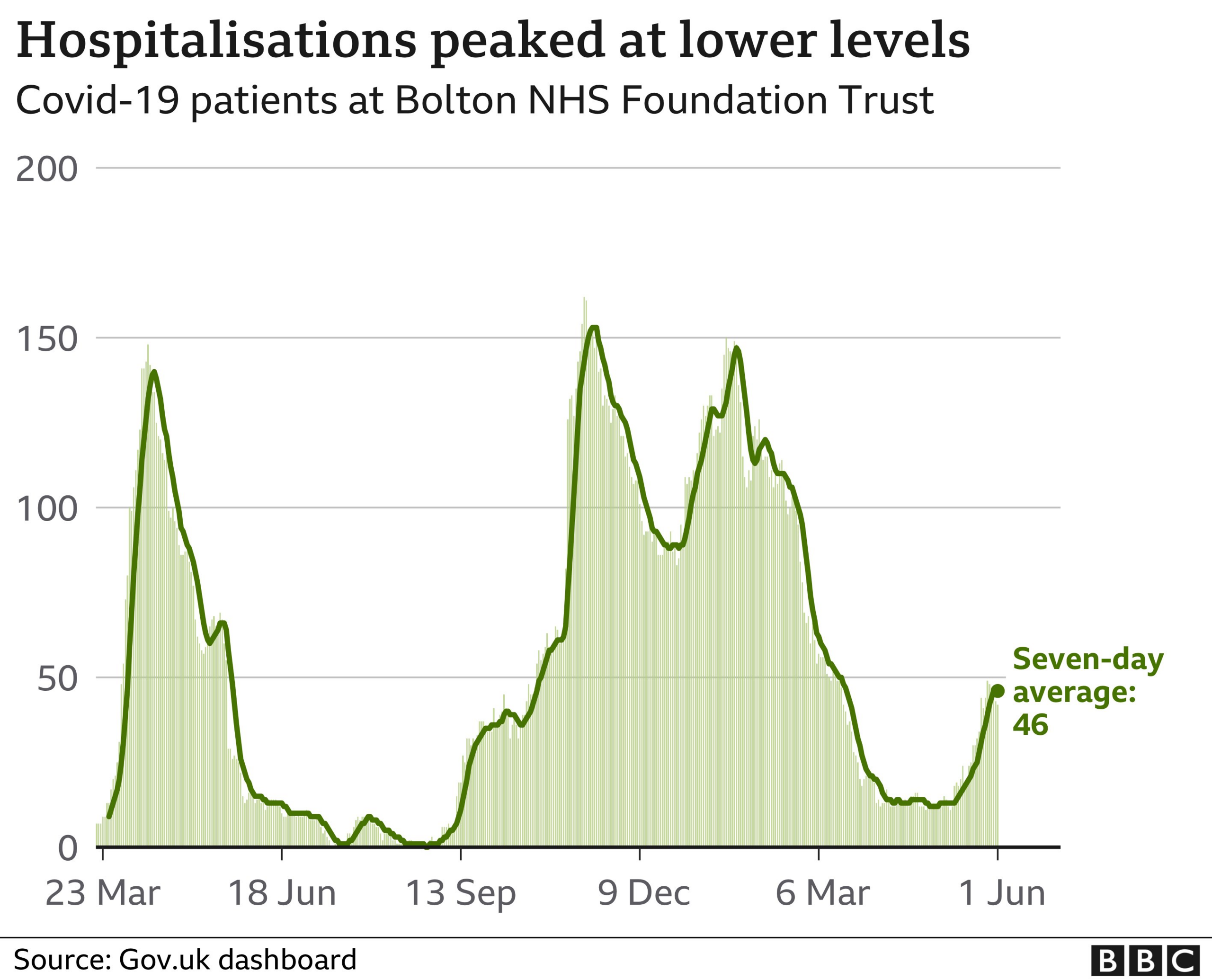

But the latest hospital data is encouraging. While Covid cases surged in May to rates seen in January, the number of patients in Bolton Royal appears to be peaking at a much lower level. Government figures show 46 patients being treated for the disease compared with more than 150 in previous peaks. Local data shows this has since dropped to 39.

It's thought just a small fraction of those in hospital in Bolton have been given two doses of a Covid vaccine. The majority are younger people who had not received the jab.

Next week the Army will leave the town as the surge testing programme is scaled back, but local officials say their work is far from finished.

"It is satisfying and we're pleased but we are really keen we don't stop," said Dr Wall. "We don't want people to read this this and think: 'Ah we are winning and so there is no need to go for that second vaccine dose'.

"We know everyone is tired and feeling it, but we can't take our foot off the brake now."

- Published9 June 2021

- Published9 June 2021

- Published1 July 2022