Domestic abuse protection orders "absolutely pointless" say victims

- Published

Domestic abuse survivors say court orders to protect them from attackers are failing

Court orders to protect domestic violence victims from their attackers are "not worth the paper they're written on", the BBC has been told.

Survivors have called for tougher measures, including electronic tagging, saying a lack of enforcement means orders provide little deterrent.

BBC analysis of government data showed prosecutions for breaching some orders have fallen by 40% in recent years.

Senior police officers have apologised, saying: "We want to do better".

Victoria, not her real name, was forced to move counties to get away from her violent ex-husband.

During their six-year marriage she was isolated from her family and friends and subjected to physical attacks, one of which led to a miscarriage, she said.

At one point, she was "only eating three digestive biscuits a day" to try to fulfil her husband's idea of what her body shape should be.

'I should be protected'

When she finally left him in 2016, she had three non-molestation orders (NMOs) put in place consecutively.

But, she said, the orders were "absolutely pointless" with her abuser repeatedly turning up at her house.

"It took a lot of courage to leave him. I had to uproot my life and move. I shouldn't have to do that, I should be protected," she said.

"There's been no support from any professionals and police didn't take the orders seriously."

Victoria said when her ex appeared in court after being arrested for a breach he was told by the judge not to do it again and freed.

That set the tone for a string of breaches, which went unpunished, she said.

Deborah Jones, who set up a support group to help survivors, says victims will only feel safe if perpetrators are electronically tagged and monitored

What are protection orders?

Restraining, non-molestation, and occupation orders are all civil orders designed to protect victims from their abusers.

It is a criminal offence to breach the terms of these orders.

A domestic violence protection notice (DVPN) is issued by police to provide immediate protection while police officers apply to the magistrates for a domestic violence protection order (DVPO). However, a breach of a DVPN or a DVPO is a civil rather than a criminal offence.

When granted by a court, terms can include bans like stopping an offender contacting a person or being within a certain distance of their home or workplace.

The Home Office is set introduce a two-year pilot scheme for a civil Domestic Abuse Protection Order in 2023, to replace the DVPN and DVPO in a bid to "provide longer-term protection for victims", the government said.

Under the scheme, electronic monitoring or tagging could be imposed to monitor a perpetrator in complying with certain terms of the order.

Kath, also not her real name, left her husband following nine years of physical and coercive abuse and has had an NMO in place since December, which he breached, she says.

"That non-molestation order isn't worth the paper it's written on," she said.

"It don't make any difference whatsoever because it's certainly not made him stay away."

She also cited a lengthy wait for legal aid funding as one of the obstacles in obtaining the order promptly.

Deborah Jones, from Barnsley, who set up support group Resolute to help survivors, said the orders were failing victims because there was "no deterrent at all for a perpetrator to breach them numerous times, over and over again".

"They get clever and very aware of the legal system," she said.

"They know that there's no real consequences to breaching them.

"Things need to change. There needs to be tougher consequences if an order is breached, perpetrators should be tagged."

According to data gathered by the BBC, figures from the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services and the Ministry of Justice show:

About a quarter of DVPOs issued have been breached every financial year between 2018/19 and 2020/21.

Convictions for breaching domestic violence-related NMOs have dropped by 7% in the last five years, despite the number granted rising by 48% in the same period.

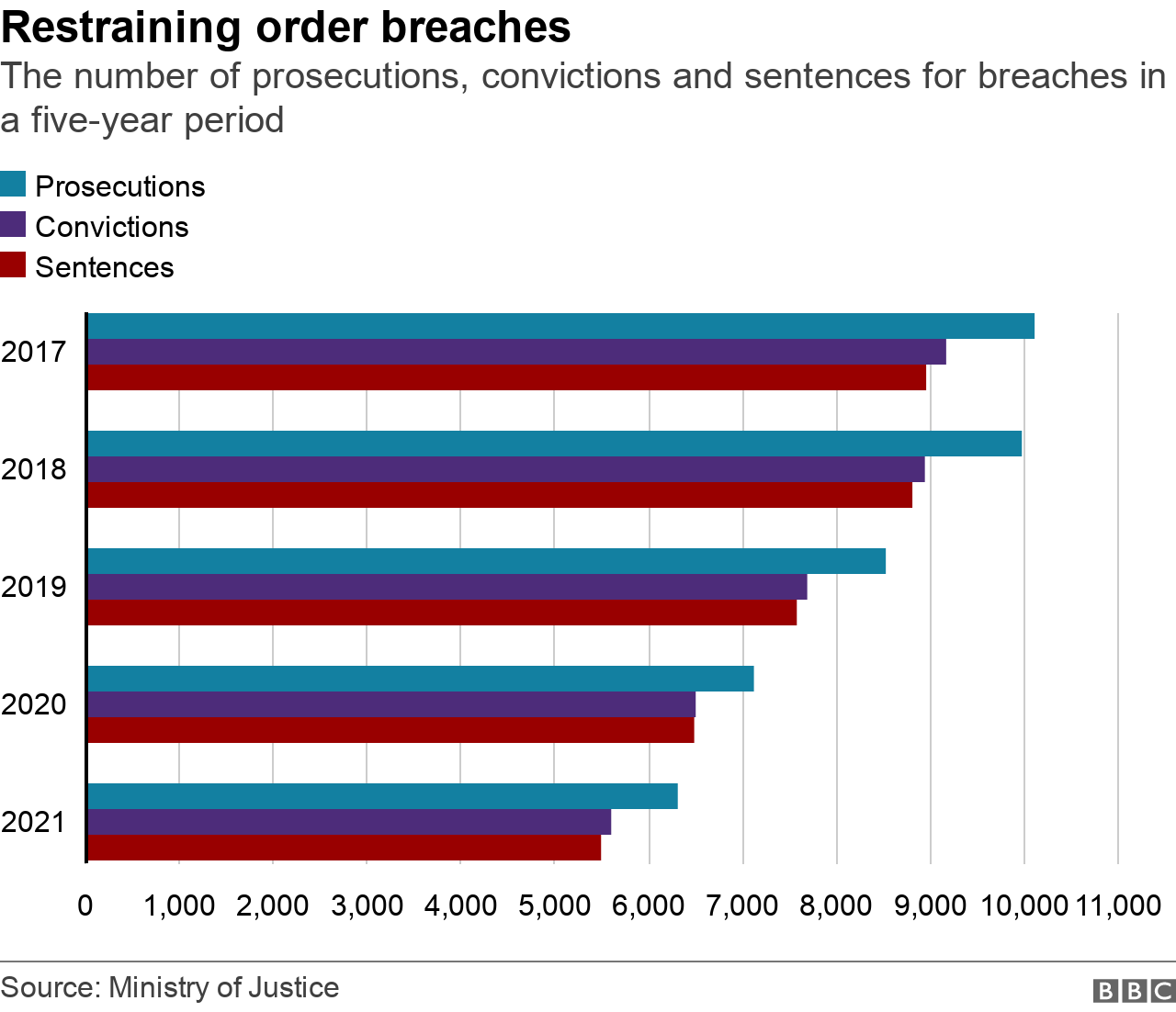

There has been a year-on-year drop in prosecutions, convictions and sentences for breaches of restraining orders between 2017 and 2021.

The Independent Domestic Abuse Services (IDAS) charity said many survivors felt breaches "are not acted upon", which in in turn undermined their confidence in the police and prevented further breaches from being reported.

IDAS's Carmel Offord said a 2018 review led by the charity found the way authorities worked left "significant safeguarding black holes".

The charity has been working alongside North Yorkshire Police on a pilot scheme, which allows officers to record orders centrally on the police national database and access relevant details when breaches occur, says Ms Offord.

"I think it really comes down to everybody working in collaboration with the safeguarding of victims, survivors and their children at the heart," she said.

"We can't just assume that a perpetrator isn't high risk because there isn't violence or they haven't done something that we would deem to be risky."

Carmel Offord, from IDAS, says survivors need to be heard and systems must in place to understand the wider picture

'Just petrified'

Emma, not her real name, said she was subjected to "seven years of absolute cruelty and torment" by her ex-husband.

She had a DVPO and then an NMO put in place from 2017 but, she says, he repeatedly breached them.

She said "nothing was done" when she reported the breaches to police and he even rented a flat as close as he could get to her home without breaking the terms of the NMO.

"My ex-husband had made threats to kill me," the mother-of-two said.

"I was just constantly looking over my shoulder all the time.

"Pulling into a car park, if his van or car was there, I would have to drive away. Just constantly living like that.

"We were just petrified, fearing for our lives. We didn't feel safe whatsoever. We were just waiting for something to happen."

The National Police Chiefs' Council (NPCC) lead for domestic abuse, Louisa Rolfe, said she was sorry that victims "have not had a service they should expect and deserve from policing so far".

"But we are working on this. It is a priority, and we want to get so much better at it," she added.

Louisa Rolfe said police were working with the Home Office and the Crown Prosecution Service to "monitor the impact of the actions we take"

Ms Rolfe, an assistant commissioner with the Metropolitan Police, said forces were using DVPOs effectively and a domestic abuse training programme meant officers nationally were being equipped to understand and "identify high-risk behaviour".

Breaches required a multi-agency approach, including the Crown Prosecution Service, she said.

"We want to support victims. We want to ensure their safety. This is a huge priority for policing, and we are really clear that we expect officers to take positive action."

If you've been affected by the issues raised in this report, details of organisations offering information and support are available via BBC Action Line.

However, the Centre for Women's Justice (CWJ) said they had seen little improvement from UK forces following recommendations it had put forward since lodging a super-complaint in April 2019, external.

The action addressed alleged failings by police in their use of protective measures to safeguard victims and was subsequently upheld by three policing bodies, external.

The charity has asked Domestic Abuse Commissioner Nicole Jacobs to approach all police and crime commissioners (PCC) to hold forces to account.

Ms Jacobs said she was "very concerned about poor enforcement of protective orders".

The CWJ is also calling for improved data gathering around breaches. When the BBC submitted freedom of information (FOI) requests to all 46 UK police constabularies, of the 34 who provided data each responded with differing or partial information.

The NPCC said the use of different IT systems by police forces meant collating statistics was a "challenge" but added that there was a "move to a more digital justice system".

Nogah Ofer, from the Centre for Women's Justice charity, says they want police forces to be held accountable for the lack of response and enforcement of breaches

Nogah Ofer, a solicitor at the CWJ, said there was also a lack of "measurable outcomes" and police training on domestic abuse did not include protection orders.

"It's not really apologies that we're looking for," she said.

"We're just looking for improvements on the ground and for victims to get a better service."

- Published2 February 2022