Has a decade of badger culling worked?

- Published

The first cull zones were created in 2013

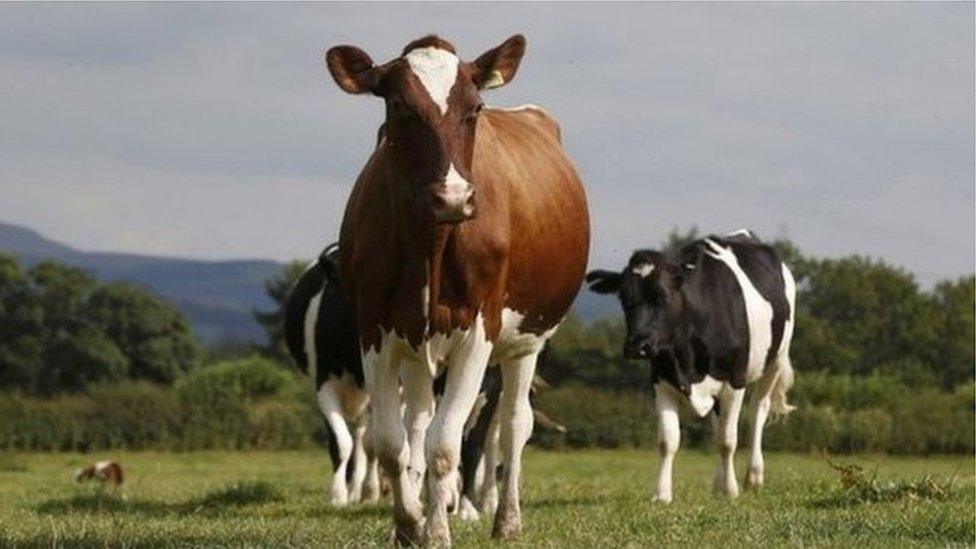

It is 10 years since the start of the badger cull which aimed to help control the spread of bovine tuberculosis (bTB) in cattle.

The cull began in Gloucestershire in 2013 and spread to Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Dorset.

Eventually Shropshire and Staffordshire also started culling.

Today, from the initial handful of cull zones, there are now more than 70 covering almost all of the West Midlands.

Scotland is officially bTB free so doesn't cull.

More than 210,000 badgers have been killed in the decade since, as well as more than 330,000 cattle, but in England at least the government wants to bring the culling to an end and vaccinate the badgers instead.

The first place to switch from killing to jabbing is the corner of Gloucestershire where the cull started so I went back to talk to farmers, vets and wildlife experts about what happens next.

But first the big question, did the cull work?

In humans with TB, treatment is relatively expensive and recovery takes a while; cattle are very similar and unfortunately that makes treating bTB uneconomic for farm animals - If they get bTB they are culled.

Culling infected animals is also an attempt to control the spread of the disease.

Cattle spread the disease to each other, but they can also catch it from badgers.

The argument for a cull says bTB cannot be controlled by only killing the cattle, you need to kill badgers as well as they represent another source of infection.

Ten years on, if you look at the data, you could see signs of things improving for cattle and farmers.

The number of cattle with bTB going for slaughter in England in 2022-23 was 20,228 a 24% fall on the previous year and the lowest number since 2008.

Wales has seen a 5% decrease over the same period.

More than 20,000 cattle in England were slaughtered in 2022-23 in an effort to tackle bovine TB

The trend in the number of cattle herds with a new bTB outbreak also shows a drop - depending how you look at it, quite a substantial one.

Does this mean we can say the cull worked? Well scientifically no.

To do that we need to compare areas with a cull to those without and we can't do that because the culls are now everywhere.

However a spokesperson for Defra, the environment department, said the government's strategy "has led to a significant reduction in this insidious disease".

Now the cull has finished in Gloucestershire - and will soon finish elsewhere - ministers are moving to a vaccination policy instead but farmers are worried that it might not work.

They argue it's going to be hard to tell if vaccination is working at all as the effects of culling could persist for about three or four years.

And the government is only funding the vaccination for four years. Untangling what's responsible for any change in TB rates in that time will be impossible.

The change in approach would, Defra's spokesperson added, be "building on the progress made" and include wider badger vaccination with better cattle testing and a move towards a vaccine for cattle.

Interestingly in Gloucestershire more farmers have signed up for the vaccination programme than ever signed up for the cull. They all hope this new approach works.

But on the ground, they think it might be 10 years before we can see clearly how things have worked out and if badgers and cattle are all living healthier, disease-free lives.

Or if all the gains so painfully realised over the last decade have been thrown away.

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published28 January 2021

- Published17 August 2020

- Published5 March 2020

- Published9 September 2019

- Published9 October 2015