Stevenage: The town that aimed for Utopia

- Published

Stevenage at 70: A look back at Britain's first New Town

Seventy years ago, Stevenage in Hertfordshire was designated the UK's first New Town. Devised as a radical solution to London's post-war housing crisis, the aim behind its creation was ambitious - but how close did that vision get to reality?

Viewed on a grey November day, Stevenage town centre is perhaps not seen in its best light.

The wind whips loose leaves round a large public square dominated by a Mondrian-inspired clock tower and fountain. Faded, tired concrete is visible as far as the eye can see.

It is a bit bleak. Many of the buildings look in dire need of a bit of TLC and no-one seems keen on hanging around to people-watch or admire the view.

Grey and somewhat uninspiring it may be, but Stevenage's political architect Lewis Silkin originally envisaged it as a "gay and bright" place.

Stevenage was the first of a new breed of towns created as an answer to Britain's post-war housing crisis

A concrete jungle where dreams are made?

The minister for town and country planning in the post-war Labour government saw new towns as the solution to the UK's housing crisis.

An East End boy by birth, Silkin had a passion and vision for new towns which would see the neighbourly "spirit of the slums" combine with easy access to the countryside, sports and leisure facilities in a self-contained community.

The resulting 1946 New Towns Act aimed to free people from the smog and cramped living conditions of the big cities and move them into leafy, close-knit, towns in the shires.

Building on the earlier Garden City movement, Silkin presented a Utopian vision. Stevenage, and other new towns, would be where rich mixed with poor and "a new type of citizen, a healthy, self-respecting, dignified person with a sense of beauty, culture and civic pride" would be created.

However, the path to creating such a place was not smooth.

Up until the 1940s, Stevenage had been a quiet farming town of 6,000 people. Those people were very much opposed to their town swelling to a population of 60,000.

The government was insistent, though. When Silkin visited Stevenage, he was met with a railway station sign altered to read "Silkingrad", a reference to what many felt were similarities between Silkin's approach and that of a totalitarian regime.

People who lived in Old Stevenage campaigned hard against the development of the new town - but lost

In the end, the residents lost their battle and the first "new town pioneers" moved into their new houses in the early 1950s.

By all accounts, the early years of the town were a time of great excitement for the newcomers.

Community groups were formed, businesses opened and bands such as The Rolling Stones and The Who played at the Locarno Ballroom.

"There was a great atmosphere of optimism and positivity," recalls Sharon Taylor, whose parents had made the move from London.

"There was a very strong community here because people had come away from their links with family life and friends where they'd lived before.

"For them, this was a very big step."

Ms Taylor is still living in Stevenage today. In fact, she has gone on to become leader of the borough council, and believes Silkin would recognise the town as having followed his ideals.

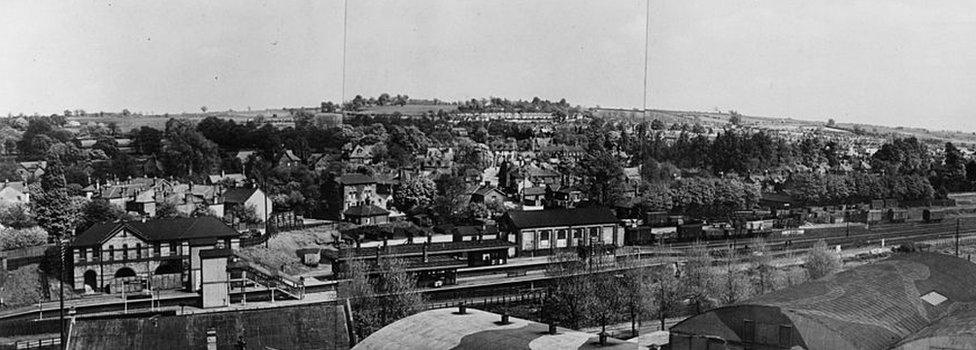

Stevenage was a small farming town when it was designated as the first New Town in 1946

When people first moved, the town centre and some housing was still being built

Stevenage's network of roads, pathways and cycleways was designed to keep residents safe

"I think the vision was incredible," she says. "The green spaces are certainly here - people are always surprised when they come here by how green it is.

"We've got about 300 community groups and we're rich in culture."

In her office, a drawing of Lewis Hamilton adorns the wall. He is one of several well-known sporting and cultural figures to have been born in the town.

Stevenage is proud of those connections and has filled a walkway between the shops and the leisure centre with pictures of the famous faces.

Stevenage sons (and daughters)

A walkway between the town and leisure centre celebrates Stevenage's well-known sons and daughters

Lewis Hamilton (born 1985), Formula One World Champion

Jack Wilshere (born 1992), footballer

Ian Poulter (born 1976), golfer

Ashley Young (born 1985), footballer

Kevin Phillips (born 1973), footballer

Ed Westwick (born 1987), actor

Cathy Lesurf (born 1953), folk singer-songwriter

Leslie Phillips (born 1924), actor

But the town is let down by its ageing concrete centre. Regeneration plans have been mooted, approved and shelved several times over.

"People judge the town on the town centre," admits Jo Ward, curator of Stevenage Museum.

"It was the country's first pedestrianised town centre, and it was revolutionary, but it has dated.

"The problem is concrete doesn't age well - it gets rain streaked and dirty, and you let all us individuals loose and we start pebble-dashing it and sticking bits on and individualising the houses, and all that uniformity is gone.

"It's more quirky and characterful but few people would be big on Stevenage being a place of great beauty."

A 2002 Select Committee report, external found this was a common theme with new towns. It said most were showing signs of age and shoppers were voting with their feet.

Ms Taylor said in Stevenage's case, the issues dated back as far as 1980, when the Stevenage Development Corporation - a body which had planned the town and collected all the rent for 30 years - was wound up. All the money went to the government instead of back into local hands, she says.

A plaque in the town centre remembers the involvement of the Stevenage Development Corporation

"All of our town centre buildings were handed over to the private sector - we've not been able to do the regeneration in the way we would have wanted to," she said.

"But we've been working hard to do a new £2 billion scheme and I feel more confident than I have done for a very long time that it will work."

The town's housing stock is also ageing fast.

"When you go out now, you can't move without seeing builders and scaffolding everywhere," said Grete Dalum-Tilds, project officer for Talking New Towns, a group researching the history of the UK's New Towns.

"Some streets don't look good, but in some places there is more individuality. The refurbished ones look really nice."

Since the New Town Act was passed, 21 other new towns have been officially designated across England.

But Stevenage is the one that holds a special place in the heart of Lewis Silkin's grandson Rory, who believes his grandfather was "a visionary".

"The town has nothing to do with me, but I've always felt a particular connection to Stevenage," he said.

"I think my grandfather would like what he saw. He was very aware, having grown up in the East End, that people were stacked on top of people.

"He was really passionate that new towns should have access to the countryside, so he'd recognise all that.

"I always get the impression people are proud of living here - there's a great feeling of place and that's a bit of a testament to him."

- Published1 March 2016