Luton Town: Location of new Power Court stadium 'means everything'

- Published

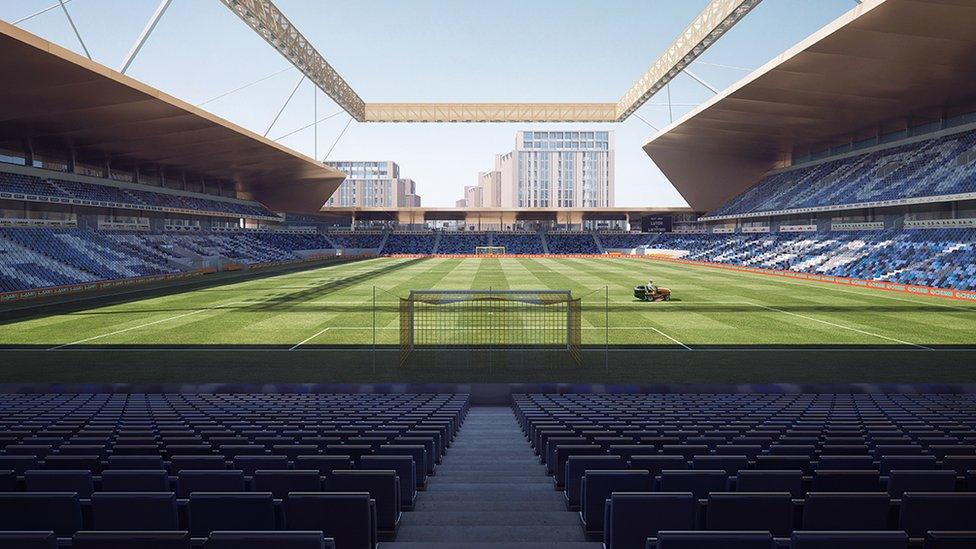

The new 23,000-seat stadium will be built on the site of a former power station in the centre of Luton

In many ways, Luton Town's Kenilworth Road stadium is the archetypal English football ground.

Hemmed in by tight residential streets on the edge of the town centre, its floodlights towering above back-to-back terraced houses, it has been the club's home since 1905 - but not for much longer.

With the 10,356-capacity ground deemed no longer fit for purpose, the Hatters are preparing to move to a new, purpose-built 23,000-seat stadium, Power Court.

But they will not be joining the many clubs to have moved to new out-of-town stadiums. Instead, their new home will be just a mile (1.6km) away on a site even closer to the town centre.

The planned move has taken its time coming - the club has been looking for a site to replace Kenilworth Road since 1955 - but has delighted Kevin Harper, from Luton Town Supporters' Trust, who says "it means everything" that the club will be staying close to its spiritual home.

"The football club has always been in the community and I think it needs the community," he says.

"It's massive for the town. It's what it brings in; it helps us fight the lure of fashionable Premier League clubs, especially with the community built around the ground.

"It's a move from the council and football club that brings everyone together."

Kevin Parker and his sister Sarah took this selfie at Kenilworth Road as Luton kicked off the 2019-20 season against Middlesbrough on 2 August

Luton Town were promoted as champions of League One last season

The club and developers 2020 Developments first lodged plans for the new stadium, on the site of the town's former power station, in August 2016 and permission was finally granted in January.

It prompted Gary Sweet, chief executive of both the newly-promoted Championship club and 2020 Developments, to set a huge target for a club that has spent its history fluctuating around England's professional divisions.

"If Leicester City can win the Premier League in a new environment," he said, "So can we."

And if that dream is realised, the supporters of clubs such as Manchester City, Liverpool and Chelsea - plus any potential Champions League opponents - would be filing through the much-maligned town centre of Luton, rather than a visiting an out-of-town development near the M1, which was a long-mooted alternative.

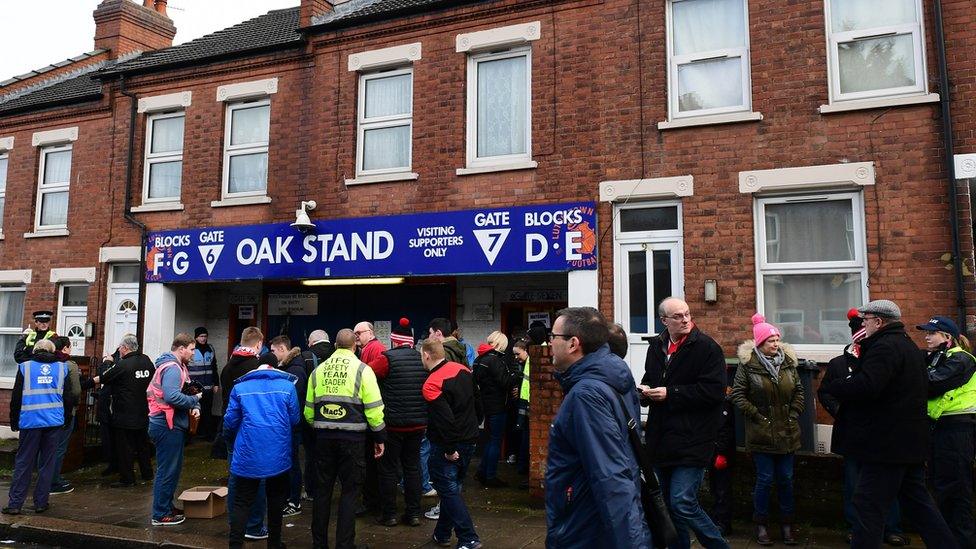

But whatever division Luton are in when they start life at Power Court, it will be a far-cry from their current offering for visiting fans at Kenilworth Road.

Supporters visiting Kenilworth Road are housed in one half of the Oak Road stand

The unconventional away fans' entrance sees visitors pass through a tight corridor before climbing staircases overlooking gardens of neighbouring properties

Last Friday evening, for the opening game of the entire EFL season, about 1,000 Middlesbrough supporters filed into one side of the Oak Road Stand through what must be the most unconventional entrance in the land, with turnstiles sandwiched between a long row of terraced housing.

After clicking and clunking through the barriers, they were led to a tight alleyway before ascending metal stairways that give the feel of being in the gardens of the adjoining homes.

Inside the ground, facilities are basic - with the toilets notoriously smelly and unpleasant - while legroom in the seats beneath a cantilever is best described as being at a premium.

Sparsely spread sheets of corrugated metal provide limited privacy for properties either side of the away entrance at Kenilworth Road

It is safe to assume such features will not be present at the proposed Power Court development, with trendy bars, restaurants and a hotel lined up instead.

Such a vision clearly stands to benefit not just the football club.

Developers have estimated the new stadium alone will generate as much as an additional £68.2m for the local economy up to July 2040, when compared with staying at the existing stadium.

Luton Borough Council said the "much needed town centre regeneration" would help Luton become vibrant both day and night, with the Hatters' new home at the very heart of its offering.

David Pleat (left), pictured here with Paul Walsh, guided Luton into the top flight of English football in 1982

This sort of town planning is nothing new of course, particularly amid a generation with the changing dynamics of professional clubs demanding a business operation outside of 15:00 on a Saturday.

But Aaron Gourley, editor of FC Business, a business magazine for the football industry, believes the Luton example is further proof the vogue for out of town moves is, if not fading, then certainly being challenged.

"I think clubs are realising that they need to be back within the community," he said. "Planners are acknowledging that football is key for regeneration.

"Look at Tottenham's new ground, and what Manchester City have done with the Etihad Campus - incorporating colleges and other facilities.

"When you move out [of the central community of a town or city] you can disconnect yourself and it's not being seen as such a good idea anymore."

Kenilworth Road is nestled in the Bury Park area of Luton

David Robinson, from the Preston-based Frank Whittle Partnership, which has worked on stadium projects of varying scale for the likes of Oldham Athletic and Fleetwood Town, takes a more pragmatic view.

"What you have to appreciate is that funding arrangements - to a large extent - impact on what happens.

"For example, Bolton Wanderers moved from Burnden Park [close to Bolton town centre] to [what is now] the University of Bolton Stadium - in Middlebrook, which is miles out and away from town and almost in the borough of Chorley.

"But the primary reason was that they could generate money from their existing site, offering something different - a food store, hotels."

Mr Robinson, a Preston North End supporter, was on the Lancashire club's board when its home Deepdale was redeveloped. , external

"The ideal position is to stay with your roots and where your father and grandfather used to watch the club. Redevelop around the same patch of grass.

"Luton, Brentford and even Man City have all had problems with access at their current or former stadiums so that's why they have maybe looked at moving rather than staying put and redeveloping."

So, perhaps there is no right and wrong in this debate - certainly with such a wide range of opinions.

Kenilworth Road is boxed in by housing on three sides, with a busway and major road on the other

And that is a view echoed by The Football Supporters' Association, formerly known as the Football Supporters' Federation, which represents fans in England and Wales.

"Some supporters do prefer the full range of modern facilities, wide concourses, and improved access or parking facilities that new build stadiums can offer," it said.

"On the other hand there can be an identikit feel to some new stadiums, while older stadiums carry a lot of history and tradition, which is important to fans."

Back in Luton, for the time being at least, the future home of the Hatters remains a long way from the grand vision shown in computer generated plans.

Power Court, which the club hopes will be open for business in 2023, is expected to be paid for by a separate leisure development at Newlands Park near junction 10 of the M1, which itself was approved in March.

Representatives from local businesses and organisations said they looked forward to having Luton Town "as neighbours" but were keen to be part of the planning process.

Power Court will be financed by 2020 Developments' planned Newlands Park development, which will offer bars, restaurants, a 1,800-capacity live venue, a hotel and car park, and 550 apartments

By moving to Power Court, Luton Town will more than double their current stadium capacity

However, it is likely an air of scepticism will hang over the project until construction work begins in earnest at the site of the former electricity power station, which was demolished in the early 1970s.

With all that said, Hatters fans will hope their new home is worth the wait.

"The town suffers from a bad image," adds fan Kevin Parker. "It needed a lift and the stadium at Power Court can do all this.

"It also helps us to compete at the next level [Championship], preserve our unique match day atmosphere and help us punch above our weight."

False dawns

The Kohlerdome had outline planning consent, but was rejected by the Department of Environment

Luton may be a Championship team now, but they have see-sawed between each of England's top five divisions in the time since their first intentions to leave Kenilworth Road.

As recently as 2014, the Hatters were a non-league club, with promotion from the Conference that year bringing a five-year spell outside the EFL to an end. But from 1982 to 1992 Luton spent a decade in the old Division One, England's top flight, and won the League Cup in 1988.

Since then proposed new homes have ranged from sites next to the M1, to Milton Keynes.

But few have stuck in the town's collective memory quite like the ill-fated Kohlerdome plan, a futuristic structure inspired by stadia from the 1994 World Cup in the United States.

The club's then chairman David Kohler unveiled the eponymously-named project in the mid-90s, with features including a retractable roof and a movable pitch - transported by means of hovercraft.

It was given outline planning permission but was ultimately rejected by the Department of Environment, with Kohler resigning after a high court appeal was thrown out - and a petrol bomb and matches posted through his letterbox., external

- Published25 April 2019

- Published11 March 2019

- Published16 January 2019