Emily Katy: 'Finding out I was autistic saved my life'

- Published

Emily works as a mental health nurse with neurodivergent children

Emily Katy was aged 13 and on a school trip when she had her first panic attack. Three years later, she was sectioned after trying to take her own life.

The 22-year-old, who lives in St Albans, was diagnosed with autism aged 16 and her life suddenly started to make sense.

She began researching the condition to learn more about herself and decided to train as a mental health nurse.

Here, in her own words, she explains her mission to support neurodivergent children and help them understand themselves.

Emily's story

I can't remember exactly when I realised I was different. Perhaps it was aged six, when I was reading The Diary of Anne Frank whilst my peers were still learning to read. Or perhaps it was when I was eight and being picked on for not fitting in. Or perhaps when I realised other children didn't love learning the way that I did.

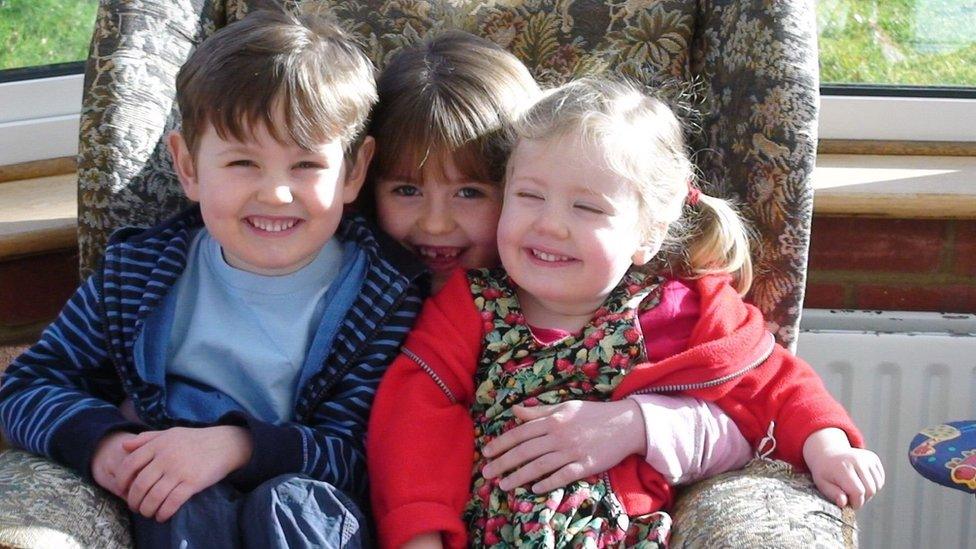

Despite knowing this, my early childhood years were filled with joy. My parents made sure I felt loved and I spent hours on end playing imaginative games with my siblings.

Emily had a very happy childhood and has always been close to her parents and siblings

When I was 13, I had my first panic attack on a school trip. This was the start of panic consuming me. I had been anxious for a while, but until this point, I had done a good job of hiding it. I had tried so hard to fit in, pretending to be like everyone else, but my brain couldn't do it anymore. Almost overnight I changed from a child who teachers loved having in the classroom, to a child teachers had to battle with just to sit in class.

Anything could trigger a panic attack, but noise, crowds, strangers, routine changes, or thoughts of death were my main triggers. School became a living nightmare. As my anxiety worsened, I started experiencing more intrusive thoughts of bad things happening to the people I loved, and of germs making my family sick. I carried out compulsive behaviours, like tapping objects to try to stop this from happening. I did not know it at the time, but obsessive compulsive disorder was intruding into my life.

Emily started experiencing panic attacks from the age of 13

Aged 14, I had some sessions of cognitive behavioural therapy, and my school put in place reasonable adjustments. But despite me rocking under tables, running away from school, and having to be taken off-site when there was a fire drill because I found the sound of the alarm too overwhelming, nobody suggested that I could be autistic. I had friends. I got A*s in all my subjects. I spoke eloquently. I was just anxious, they said.

'My distress escalated and I was sectioned'

Two weeks after starting my A-Levels, at the age of 16, I attempted to end my life. I believed that I wasn't made for this world, and that the world wasn't designed for someone like me. My parents were devastated, but they did their best to try to understand and support me. I was admitted to a child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) psychiatric unit, initially informally (meaning that I agreed to the admission).

However, after three weeks they suddenly took my diary off me because it was a spiral-bound notebook, which was a prohibited item. I wrote absolutely everything down in it and it was my only way of coping in an environment that felt so out of my control. Worst of all, it wasn't finished. And I did not know how to cope with that. My distress escalated. I demanded to be discharged and then I was sectioned.

Doctors missed that Emily's symptoms were those of a distressed autistic person

Despite having the most meltdowns I have ever had in such a condensed period of time, and despite my notes listing autistic trait after autistic trait, my doctor said: "I don't think you're autistic, I think you just have high social anxiety." This was after my parents and I had questioned it. My notes also read that "Emily has hysteric attacks when she does not get her own way". But this was because my routine had changed, noise became overwhelming, and I didn't know how to cope.

I have no idea how my autism was missed when it was so obvious. Instead, after a three-month admission, I was diagnosed with generalised anxiety disorder and mixed personality disorder. These diagnoses include symptoms of perfectionism, rigidity, difficulty expressing emotions, and other traits that can so easily describe a distressed autistic person.

Emily feels like her life only started to make sense when she received her autism diagnosis

I managed to reintegrate back into sixth form, but I was still struggling with my mental health. I was fortunate enough that my parents could pay for a private autism assessment, which was supported by my community CAMHS team. Shortly before my 17th birthday, I sat in front of a psychiatrist who told me, "I think there is one explanation for everything that you have been through, and that is autism". In that one single moment, my whole world changed. Although I understood very little about autism then, I felt immense relief. Like everything that had happened to me wasn't my fault.

'I realised I was not alone'

The next year or so was rocky, with a second admission to the unit and months under the home treatment team. I was angry. I felt like I had been sectioned because I was autistic - and not just because of growing up, masking, in a world not designed for me. I felt like the actual act of being sectioned - because of my distress from giving up my diary - was because my autistic brain was not understood. Although the unit kept me safe, and I am grateful to the staff who did help me, ultimately I left the unit more traumatised than when I had gone in.

Writing has always been my way of processing things, so I set up my blog Authentically Emily, external and began to write about my experiences. Through this, I realised that I was not alone, and I have been able to learn about myself from autistic people who have been working tirelessly in the online advocacy space for so many years.

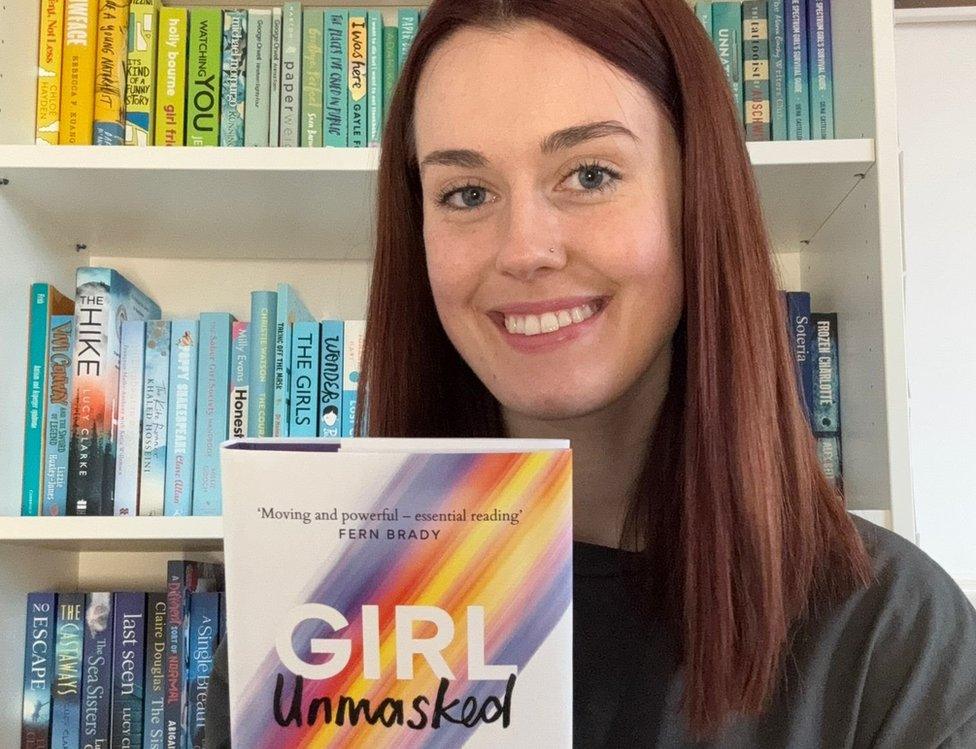

I became a trustee for the charity, Autistic Girls Network, external, and the anger of what I'd been through turned into anger at what so many autistic girls were going through, all over the country. This was the motivation for me writing my book, Girl Unmasked: How Uncovering My Autism Saved My Life. I never meant to write a memoir. But it turned out, I couldn't share what I needed to say without telling the world about myself in the process.

Emily has written a book about her experiences to try and help other people

I didn't want other young people to go through what I had. A particular nurse on the unit had helped me feel less scared and alone, and I wanted to be able to do what she had done for me, for others. Last minute, I swapped my choice of psychology degree to mental health nursing.

As I progressed through my course and my advocacy work outside of university developed, I realised my motivation had shifted. I was desperate for neurodivergent young people to understand why they feel different, to understand how their brain works, and to be properly supported to be able to thrive. In September 2022, I qualified as a mental health nurse, and started working with neurodivergent children and young people.

Last January, I was diagnosed with ADHD. This helped me understand the things autism didn't fully explain, like why it takes so much willpower to focus in conversations and not interrupt people, and why my thoughts have always seemed to race around my brain a hundred miles an hour faster than everyone else's.

I wish I could have shown 16-year-old me the future. I love working with neurodivergent children and becoming an author is a childhood dream come true. I hope that through sharing my story, it will start conversations about the importance of understanding autism in the mental health system. I want other autistic girls to know that they are not alone.

As told to Charlie Jones

If you are affected by any of the issues in this article you can find details of organisations that can help via the BBC Action Line.

Follow East of England news on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external. Got a story? Email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external or WhatsApp 0800 169 1830

- Published10 May 2023

- Published2 January 2023