Nicholas Winton's children: The Czech Jews rescued by 'British Schindler'

- Published

Sir Nicholas Winton worked with relief organisations to set up the Czech Kindertransport

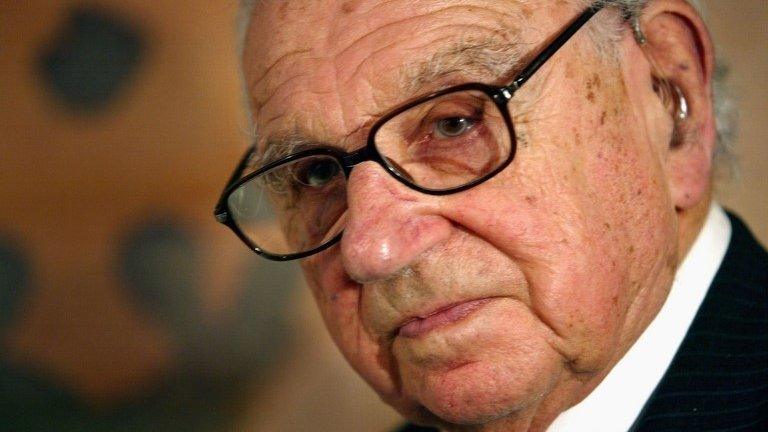

Dubbed the "British Schindler", Sir Nicholas Winton rescued 669 children destined for Nazi concentration camps from Czechoslovakia as the outbreak of World War Two loomed.

His death at the age of 106 came on the same day 76 years ago when the train carrying the largest number of children, external - 241 - departed from Prague.

The reluctant hero worked to find British families willing to put up £50 to look after the boys and girls in their homes.

His efforts were not publicly known for almost 50 years.

More than 370 of the children he saved have never been traced, external and do not know the full story.

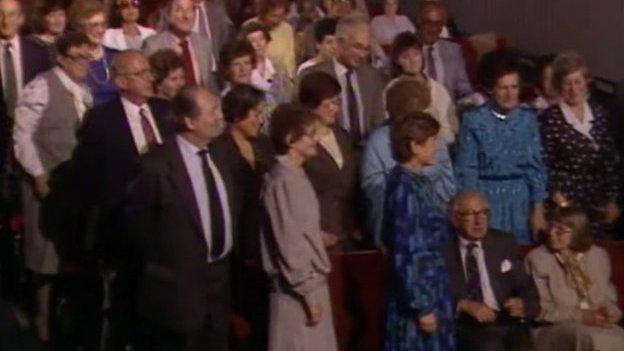

'English Schindler' Winton was reunited with rescued children on That's Life in 1988

"One day my father called my brother and me and he said, 'sit down boys, you're going on a long journey'," said John Fieldsend, now 84.

Born in Germany, Mr Fieldsend's original name was Hans Heinrich Fiege.

His family fled to the Czech Republic when the Nazi persecution of the Jews began, prior to the outbreak of World War Two.

"As the train was leaving my mother took her wristwatch off, passed it through the window and simply said, 'remember us'."

Winton set up an office in a hotel in Prague

Lia Lesser, 84, now lives in Birmingham but was originally taken in by a woman who lived on the Isle of Anglesey.

"We didn't know we wouldn't see our parents again," she said.

"I think they must have known there was a good chance they wouldn't see us again, and they were very brave to let us go."

"I never knew how my mother arranged it, she never talked about it," said Zuzana Maresova, who was born in Prague and later returned there.

She said her mother gave her a book about flowers and said, "you're going to a place where these flowers grow".

"That's all I knew," she said.

Winton helped 669 children out of Czechoslovakia in 1939

The humanitarian goals of Winton, who was born in the Hampstead district of north London in May 1909, were helped by a 1938 Act of Parliament that permitted the entry to the UK of refugee children under the age of 17, as long as money was deposited to pay for their eventual return home.

He set up an office in a hotel in Prague where he was quickly besieged by families desperate to get their children out before Nazi Germany invaded Czechoslovakia.

"There was a long queue and at the end of the queue was a small office, and we got some forms to fill in," said Ruth Halova, who was born in Prague.

"Within three months we got the names of foster parents who were prepared to take us in, and mine were a Mr and Mrs Jones from Birmingham."

The 90-year-old added: "There was a steam engine, the old wagons were made of wooden planks.

"Everybody got this label on cardboard with a piece of string with a number [on it], and then we were shoved into the carriages."

Milena Grenfell-Baines (left) and Ruth Halova are two of the people Winton rescued during his mission, which is commemorated by a statue at Prague railway station

Winton, who lived in Pinkneys Green in Maidenhead, until his death, worked with relief organisations to set up the Czech Kindertransport, just one of a number of initiatives attempting to rescue Jewish children from Germany and the Nazi-occupied territories.

He organised a total of eight trains from Prague, with some other forms of transport also set up from Vienna.

Ms Maresova said: "We were rather excited because we thought it was some kind of adventure."

However, she added the image of all the parents' "pressed faces to the windows and tears running down their faces, and wondering why they're crying", had remained with her all her life.

Mrs Lesser said: "The only thing I had was a pendant with a picture of Moses on one side, and on the other were the Ten Commandments, and that's the only piece of jewellery that I brought with me.

"Apart from that I had a Czech storybook... I had no dolls, teddy bears or anything like that. I just had two suitcases with clothes in."

Winton's rescue operation was not publicly known until 1988 when he appeared on That's Life and had a surprise reunion with some of the people he saved

"The next thing I remember was being handed over to a gentleman who couldn't speak Czech," said Ms Maresova of her arrival in England.

"He had a paper with all sorts of questions in English and Czech.

"Whenever he wanted to ask me something he pointed: 'Are you hungry? Do you want to eat something? Do you want to drink something? Do you want to use the toilet?'"

Mrs Lesser said: "In the early days I corresponded with my parents and then we corresponded through the Red Cross, and then eventually the letters stopped.

"I think that's when they were in Auschwitz."

When the war ended she said realised they had "perished".

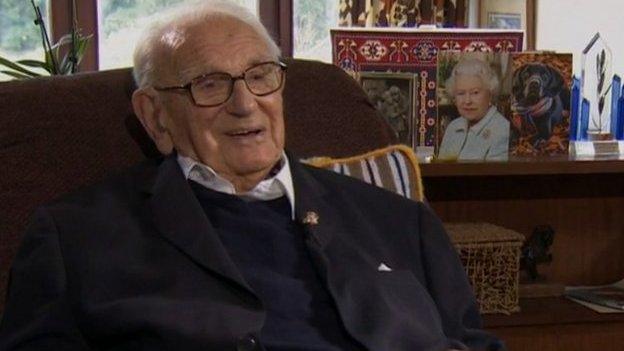

Winton was knighted by the Queen in March 2003

Mr Fieldsend received a letter just after the war, in 1946, and said his first thought was: "Hooray, they're alive."

"My mother wrote: 'When you receive this letter the war will be over... we want to say farewell to you - to our dearest possession in the world, and only for a short time were we able to keep you'," he said.

The letter went on to list other members of his family who had been "taken".

In the letter, his father wrote: "We are going into the unknown with the hope that we shall yet see you again when God wills."

Mr Fieldsend described the letter as "fantastic", adding: "What wonderful parents I had."

Ms Halova was lucky to be reunited with her mother after the war and described it as "the answering of my biggest prayer".

Some 9,000 victims of the Nazis are buried in the Jewish cemetery at Terezin Memorial, formerly the Theresienstadt concentration camp, in the Czech Republic

Milena Grenfell-Baines, 85, who now lives in Preston, Lancashire, was born in Prague and taken in by a family in Ashton-under-Lyne, near Manchester.

Her parents also survived the war but how she got on the train "remained a mystery" for many years, she said.

It was not until 1988, when Sir Nicholas's wife Grete discovered a scrapbook in their attic containing a mass of documents, including the names of the rescued children, that his heroism became known.

That year he was reunited with some of the rescued children, now adults, on the BBC's That's Life programme.

"It was an amazing surprise, but no more so than to Mr Winton who had come to the studio, totally unprepared that he was going to be confronted by us," said Mrs Grenfell-Baines, who had been invited to the TV studio without being told why.

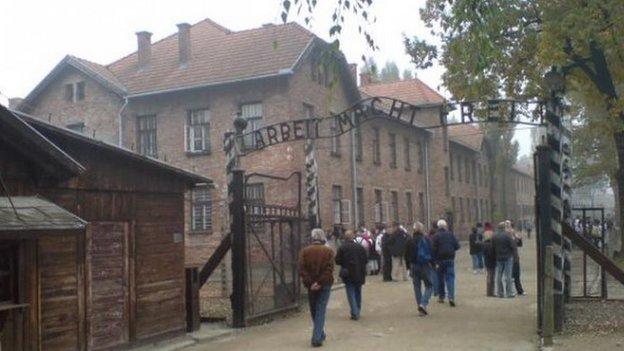

More than one million people, mostly Jews, were murdered between 1940 and 1945 at Auschwitz in German-occupied Poland

Ms Halova described Winton as "an exceptional human being", adding: "We loved him from the first moment - who wouldn't love Nicky?

"He took so many risks and it was such a brilliant piece of organising," said Mr Fieldsend of Winton's efforts.

"I just thought it was amazing that a single human being could save 669 children and nobody knew about it," she added.

"Nicky, I am so proud to be one of your very many children."

Winton, whose work has been likened to that of the "saviour" of Jewish prisoners Oskar Schindler, was knighted by the Queen in March 2003.

A year earlier he was reunited with hundreds more of the children he saved, including Labour peer Lord Dubs and film director Karel Reisz.

Interviews compiled by Chris Browning for Saved by Sir Nicholas - a BBC Radio Berkshire documentary.

- Published1 July 2015

- Published28 October 2014

- Published28 October 2014

- Published18 September 2010