Caversham Park: End of an era for BBC listening station

- Published

BBC Monitoring began in 1939 as an operation to allow the British government to access foreign media and propaganda during World War Two

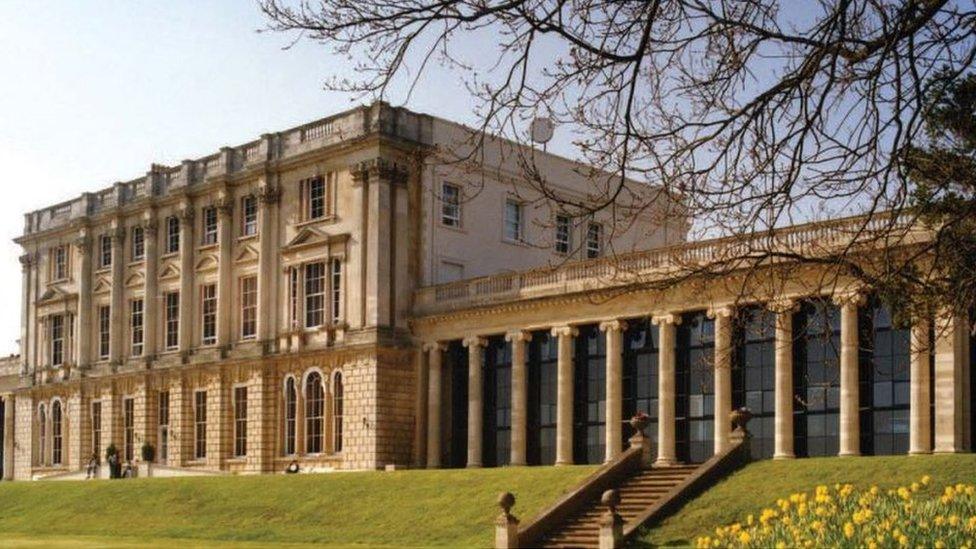

For nearly 75 years BBC staff at a sprawling stately home on the outskirts of Reading have been listening in to some of the world's most seismic events, from Nazi Germany's occupation of Europe to the death of Stalin and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Since 1943 Caversham Park has been the home of BBC Monitoring, whose offices still summarise news from 150 countries in 100 different languages for the BBC.

But after a £4m funding cut, the remaining journalists, academics and translators are to leave the country estate for new offices in London.

As the international newsgathering service enters a new chapter of its life, BBC News examines how Caversham Park shaped the news agenda in the mid-20th Century.

World War Two

The monitoring service began at the outbreak of war with Germany in 1939, with its primary purpose to inform the War Office of propaganda by Nazi-controlled media outlets and the broadcasts of other Axis Powers.

At its inception in 1939, BBC Monitoring was based in a set of shacks in Wood Norton, Worcestershire, but by 1943 it had commandeered Caversham Park, which was being used as a hospital at the time

Transmissions from the Axis Powers began being recorded on phonograph cylinders in 1941

It initially set up camp in shacks around Wood Norton, Worcestershire, but by 1943 the service had commandeered Caversham Park, which was at the time being used as a hospital.

The recorded history of the site goes back to the Domesday Book, when it was inhabited by relations of William the Conqueror, but by the 20th Century it was being used by the Catholic Oratorians as school. By 1941, the premises had been transferred to the BBC.

Caversham Park was procured by the BBC in 1941 and has remained under its ownership, but for many years its purpose was kept secret due to the work it did for the UK government

Monitoring staff at Caversham would transcribe and summarise 240 broadcasts into an 80,000-word document called the Daily Digest. This was swiftly delivered to London by war despatch drivers.

BBC Monitoring played a key role in tapping communications made by Hellschreiber (a kind of teleprinter) from Nazi Germany's propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels to newspaper and radio networks. A site outside London was chosen in part because it was less likely to suffer bomb damage.

By the end of the war 1,000 people worked at Caversham Park helping to provide the War Office and BBC journalists with up-to-date information from Axis Power news agencies.

The Daily Digest was transported from Berkshire to London for distribution each day at 10:15

People of many nationalities worked at the monitoring station, including German-Jewish refugee Karl Lehmann, whose family fled Nazi rule.

He said: "It was a very sociable place to work, in fact staff would often come in on their off days and eat in the canteen, which greatly eased the effects of rationing.

"There was a library in the building, and the park - so a pleasant place to spend a day off. In fact the building was almost like a club and the service was like one big family - even though there were nearly 1,000 of us here in total, from monitors to engineers and editors.

"We were all totally united in the one aim of winning the war."

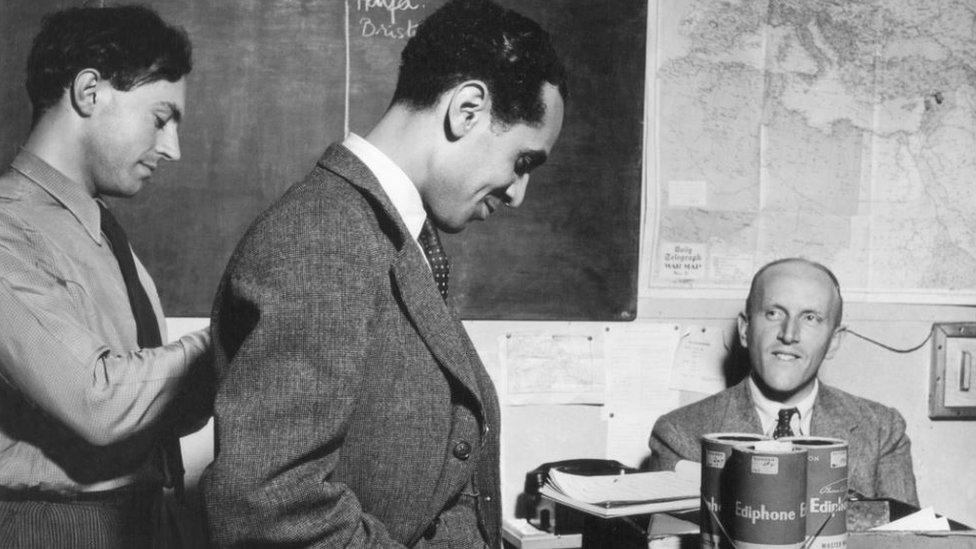

From as early as 1941, BBC Monitoring employed Arabic interpreters to translate messages from Tunisia and Iraq

BBC Monitoring kept up-to-date maps on the latest attacks and offensives during World War Two

Throughout the war, some staff at BBC Monitoring lived at Caversham Park, and had to do all of their daily chores in communal areas

The Cold War

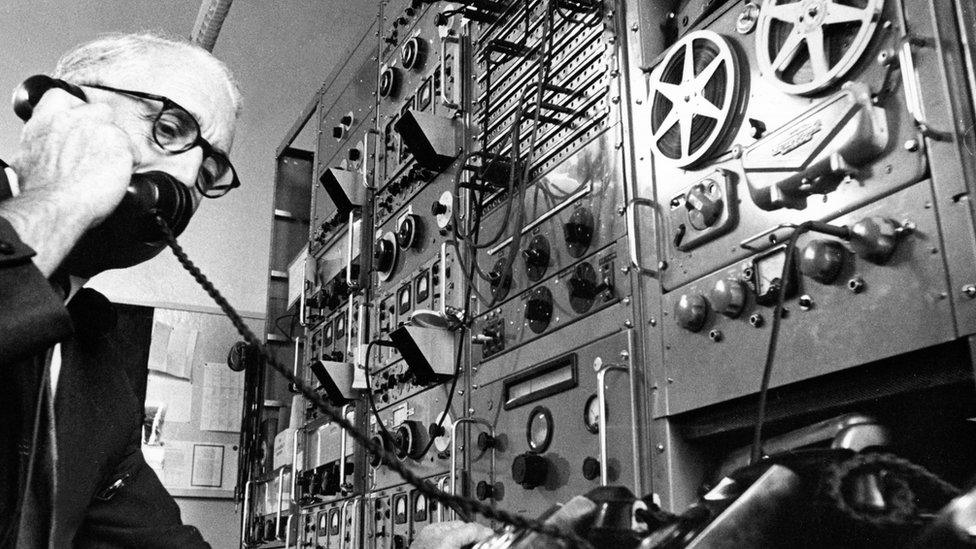

Technical operators, like the one above, pictured in 1953, would have to ensure that translators could monitor up to 3,000 media outlets a day

Shortly after the end of World War Two the service halved to about 500 members of staff, and attentions were turned to the burgeoning threat of the Soviet Union. The service covered the Soviets' invasion of Hungary in 1956 and the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961.

It played a key role in the Cold War, monitoring the events of the Cuban Missile Crisis as the USA and Soviet Union came close to nuclear conflict.

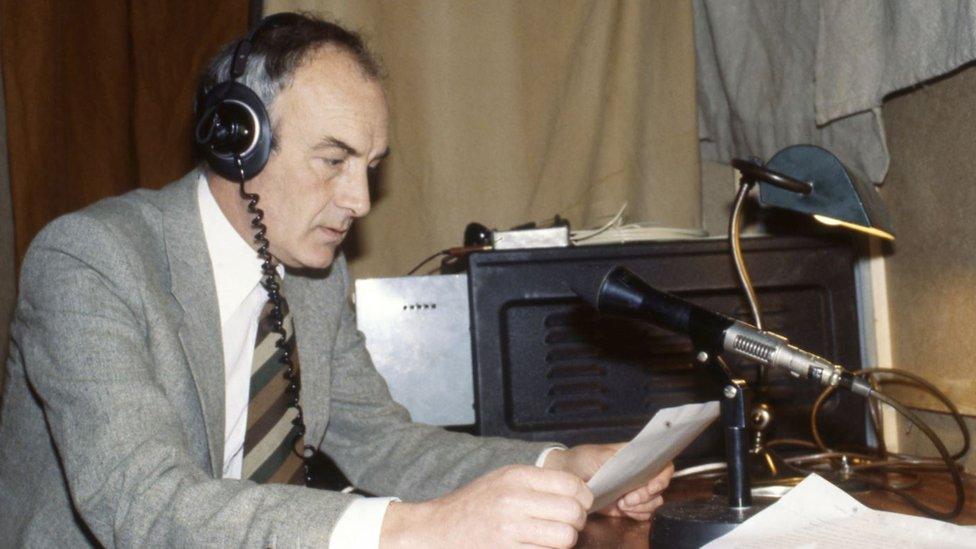

By the 1960s, Monitoring's attention had moved towards the Soviet Bloc, and about 500 members in Caversham monitored the propaganda from the Soviet Union

In 1962 President John F Kennedy told Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to dismantle Russian missile sites in Cuba or "face the consequences".

BBC Monitoring listened in to Khrushchev's response, which was broadcast on Moscow radio.

He said: "The Soviet government has ordered the dismantling of the bases and the despatch of the equipment to the USSR. I appreciate your assurance that the United States will not invade Cuba."

Monitoring contacted the White House through its US counterpart before Kennedy received Khrushchev's official response.

Author and journalist Michael Smith worked at Caversham Park initially as an engineer, and then as a journalist in the 1980s until 1990. He said: "I'm sure [BBC Monitoring] were part of it and important. At that stage their ability to know what was coming from Russia was tremendous."

When in the UK, Warsaw Correspondent Kevin Ruane would visit BBC Monitoring and make broadcasts from the transmissions received by operatives at Caversham Park

He added: "We were able to report on global news without being on the front line; it really crossed the divide between news and intelligence-gathering.

"I remember being the duty editor and news of the fatwa on Salman Rushdie came through from [Iranian] radio. At that time no-one in England knew what a fatwa was."

The service today

BBC Monitoring was one of the first Western agencies to break the news of the assassination of Col Gaddafi

BBC Monitoring still listens in on radio transmissions from around the world, as well as translating and analysing print journalism in 100 different languages, but the journalists and academics now have the added task of scouring the internet for news.

In 1991 the Berkshire-based listening post heard a live broadcast of Somali rebels taking over a government-run radio station in Mogadishu at the outbreak of the country's civil war.

Monitoring also analysed the fall of Gaddafi during the Libyan Civil War by listening to medium-wave radio signals and using satellites to watch TV broadcasters in the country.

Throughout World War Two and the Cold War, little was known of BBC Monitoring and it was heavily financed by the Ministry of Defence and Foreign Office, as well as the World Service.

But in 2010 during licence fee negotiations, it was decided that BBC Monitoring would be funded by licence fee-payers. Currently it employs 320 staff in all corners of the globe, but the one constant that has remained for nearly 75 years is its base in Reading.

For more than half of the 20th Century, staff at the idyllic country house eavesdropped on the world, but shortly that will be no more.

Mr Smith said: "It's a tremendous shame that we're getting rid of it."

Related topics

- Published5 July 2016