The German and British children who became post-war friends

- Published

June Whitcombe and Gretel Rieber met after the war as a special relationship developed between Reading and Dusseldorf

In 1947 Germany and the UK were both still reeling after World War Two. But in Reading that did not stop the mayor, in the face of fierce criticism, inviting impoverished children from the city of Dusseldorf to her town. The twinning still thrives, and resulted in a life-long friendship between Gretel Rieber and June Whitcombe.

Gretel Rieber was 12 years old and living in poverty when she was pulled out of class and put on a boat to the UK.

Excitedly waiting for her arrival in the English town of Reading, Berkshire, was 13-year-old June Whitcombe. Seven decades on, she still vividly remembers returning home from school to find her new "German sister".

"When I first saw Gretel I was quite disappointed because she looked quite normal," says Mrs Whitcombe, recalling that day 70 years later.

"I hadn't met a German person before. I had only seen what was depicted in cartoons and, of course, propaganda and what we read about the bombing.

"I thought she would at least maybe have horns and two heads. All I knew of Germany was that it was bad and it was evil."

Poverty was spreading in Dusseldorf after it was bombed by Allied forces trying to break the Nazis' resolve

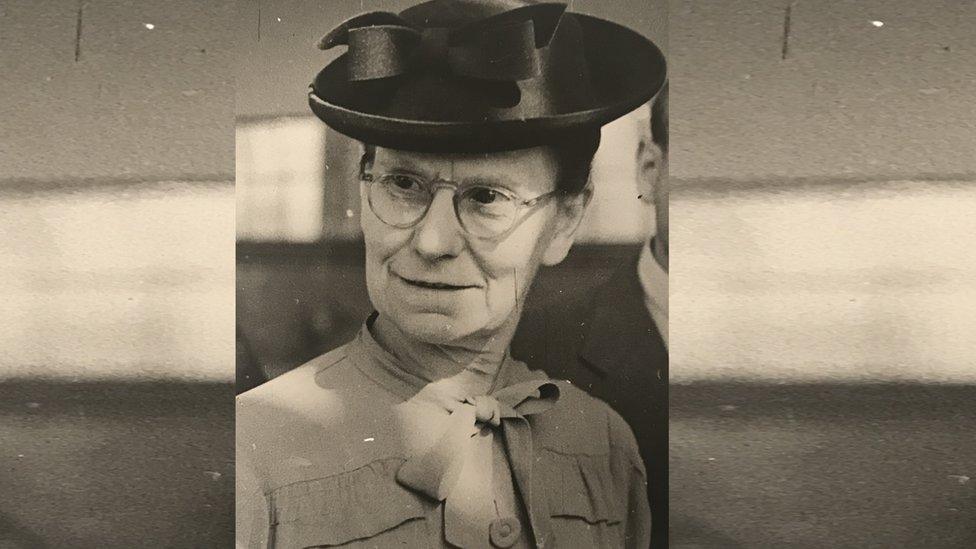

The Royal Berkshire Regiment was occupying Dusseldorf and witnessed first hand widespread hunger and homelessness. Soldiers reported this back to Reading mayor, Phoebe Cusden.

They told her how poverty was spreading after the city was reduced in parts to rubble by Allied forces trying to break the Nazi's resolve. Historians say some 56,000 people were living in ruins, cellars and bunkers.

Moved by their stories, the mayor visited the city herself and was shocked by what she found.

She penned a plea for help in the Berkshire Chronicle that resulted in half-a-tonne of food parcels being donated, ultimately paving the way for her ambition of bringing an initial six impoverished children to Reading.

She wrote at the time: "The condition of the poorest family in Reading is many times better than the average family in Germany.

"It would surely be disastrous to any hope of rebuilding Europe if we allowed the German people to believe, as they are already beginning to believe, that we are deliberately starving them."

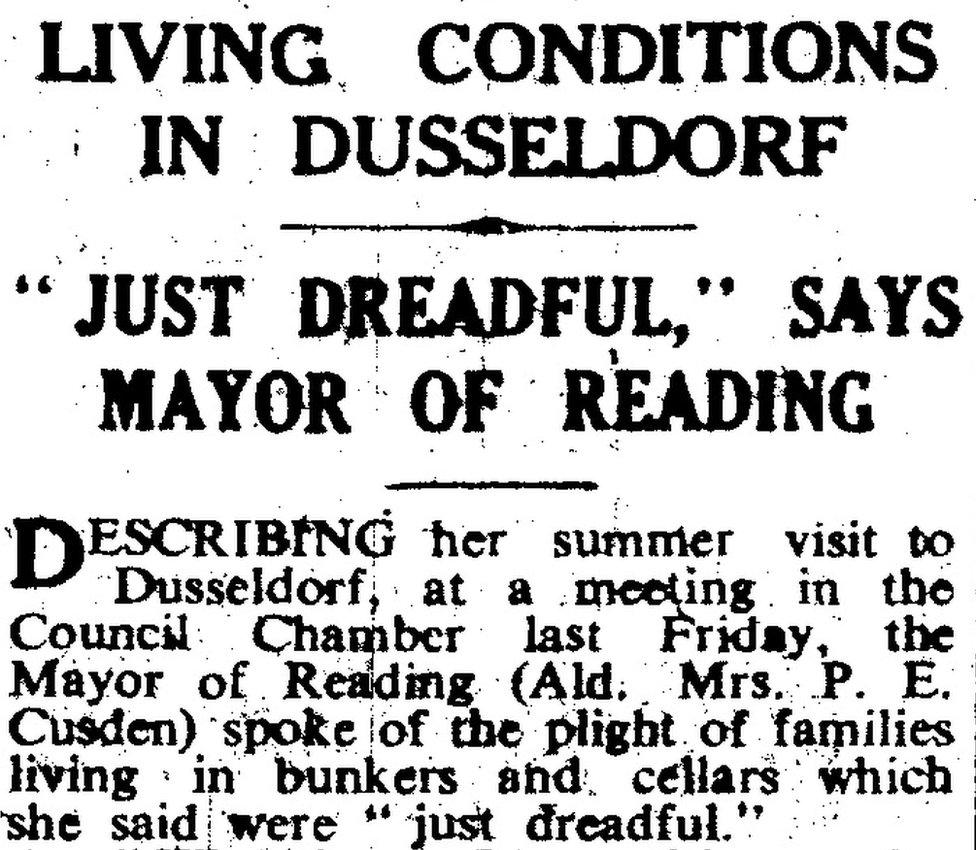

An article about Phoebe Cusden's visit to Dusseldorf was published in the Berkshire Chronicle in September 1947

In response, the paper received furious letters from residents of Reading, a large town 40 miles west of London then known for its beer, biscuits and bulbs.

One particularly angry letter read that "we still cannot trust the Boche" and that "he himself should work to feed his children - it is not our job".

The Reading branch of the British Legion was also opposed, releasing a statement which read: "We are of the opinion that any such assistance should first be applied to the necessitous cases in our own Borough of Reading."

But June, an only child living with her parents, was determined to help Mayor Cusden bring the children to the town and was on the phone to her "straight away".

"Phoebe said 'I better speak to your mother', and thus we had Gretel," Mrs Whitcombe recounts.

Phoebe Cusden was moved to act after reading that many of the children in Germany's worst affected areas were living on as little as 400 calories a day

Gretel was one of those children suffering, one of those whose parents struggled to put food on the table every night.

"The headmistress came to the classroom and said 'Gretel can you come to my office please?'" says Mrs Rieber, now 81.

"There were two other girls there with me, and she said 'you are going today, to England, for three months'. And just like that, I was on my way."

She remembers leaving her suburban home in Dusseldorf, which she remembers as a "city in ruins", to a boat and being handed £1 by a British official for the journey.

"I was hungry and with that money I went to the bar on the boat and ordered a sandwich," says Mrs Rieber.

"When I arrived in Reading I said to Mrs Coleman, my foster mother, 'here is my money - the rest I ate'."

Gretel recalls enjoying her time in Reading with June's family

That was an anecdote the family smiled about and recounted for many years after, and broke the ice at a time when the prospect of Germans visiting was an unsettling one for some in the community.

Mrs Rieber says, although she was only ever treated with respect from the British people she encountered, she was aware of why there might be an anti-German sentiment.

"I can understand that they didn't want us. We had been their enemies.

"Not myself, not my parents, but Germany had been terrible enemies for Britain.

"But I never had a feeling that I was not welcome."

She adds that the ill-feeling towards Germans was not prompted by just propaganda.

"The majority of Germans were followers of Hitler so in a way it was true," she says. "I knew very early - when I was maybe six or seven - that Hitler was bad."

Teachers at the pair's school urged Gretel (bottom row, second from right) to teach June (top left) and the other children German

Mrs Whitcombe remembers the shame Gretel felt when she first arrived, and watching her struggle with violently vivid nightmares.

"When she first came to England she said she wished she wasn't German, but that changed rapidly. I don't think she wanted to talk about home," says Mrs Whitcombe.

"I am very proud of my mother and father. They opened their hearts and their home to her at a time when most people wouldn't.

"We didn't have much abuse, but nevertheless not many people were doing it."

Teachers at the pair's school urged Gretel to teach the other pupils German and she quickly integrated into British life.

At the family home, June had to get used to having a sibling while Gretel began to accept she would no longer be left to go hungry.

June remembers the shame Gretel initially felt when she arrived at her family home

Mrs Whitcombe recounts how she once discovered Gretel eating chocolate in the middle of the night, the young German girl feeling the need to be surreptitious - back at home she always feared people taking her food away.

They soon became inseparable and June's mother treated them as if they really were sisters.

"I always said if you share a knicker drawer then you are friends for life," says Mrs Whitcombe.

"Gretel didn't have any clothes. She had virtually nothing. I mean her dress was a flour sack. My mother gave up - we just had communal clothing."

The knicker drawer theory proved correct - they continued to visit one another long after Mrs Rieber returned home as conditions in Germany improved.

During a conversation recorded for a BBC Radio Berkshire documentary, Mrs Whitcombe tells her old friend: "I reckon you and I are the oldest twins in Europe."

"We were just two normal kids going to the same school."

Mrs Rieber says she hopes others will benefit from the Reading and Dusseldorf twinning

And Mrs Rieber credits the Reading and Dusseldorf twinning, formalised in 1975, for helping hundreds of children broaden their horizons.

She says she hopes others will form the bonds and experience the kind of formative moments she was lucky enough to have because of the relationship.

And with the Reading Dusseldorf Association still flourishing, its events calendar as busy as ever, the legacy of Mayor Cusden's project lives on for another generation.

But the original generation are still close.

As Mrs Rieber says goodbye, the women tentatively arrange a trip away together to Israel.

"Next year - I'll see you in Jerusalem," she tells her "English sister".

Listen to Reading and Dusseldorf: The Tale of June and Gretel on BBC iPlayer.