Birmingham tunnels: 'A plaster on a festering wound'

- Published

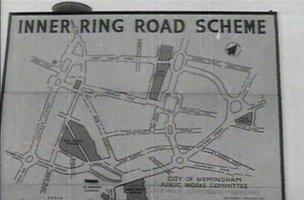

The tunnels were built as part of the inner ring road in the 1960s and 1970s

Work is starting on Birmingham's Queensway and St Chad's tunnels, closing them completely for six weeks.

City council officials say the structural repairs, new lighting and fire safety measures are essential to make sure they last for the years to come.

For others it is a bleak confirmation the tunnels are here to stay.

"In a way, it feels like just rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic," said urban designer Nick Corbett.

"I can understand why they're doing it - they look horrible, they carry tens of thousands of cars each day and they need to be reasonably attractive - but I don't think they're the best thing for the long term.

"Carrying out this work is like putting a plaster patch on a festering wound."

Untouched

The tunnels first made their mark on Birmingham and contributed to the city's "concrete collar" when the inner ring road was built during the 1960s and 1970s.

The landmarks which sit on the A38 between Spaghetti Junction and the city centre have remained virtually untouched during that time.

Last year, the Birmingham Mail reported engineering consultants Atkins were commissioned by the council to come up with ideas of what to do with the tunnels in the long term, external.

The newspaper said engineers came up with three options: demolish the St Chad's tunnel and slightly extend the Queensway tunnel at the cost of £85m; join the two tunnels to create a continuous tunnel from Lancaster Circus to Suffolk Street for £64m; or the third option of sprucing up the tunnels as they are at the moment.

Council leaders opted to go with the third option - at least for the time being - which will mean the tunnels are shut for six weeks this summer, plus overnight for the following fortnight.

The cost of that option is included in the city council's 25-year £2.7bn contract with Amey to maintain Birmingham's roads, footpaths, bridges, tunnels, street lighting and traffic control systems. Amey has not said exactly what proportion of that is being spent on the tunnels.

The city council said the work on the tunnels was essential and had needed to be done quickly.

1980s gloom

But Mr Corbett said it would have been in the city's best interests to come up with a long-term view of what could happen to the tunnels before spending any money on a revamp.

"At present we've got the worst of all worlds," said Mr Corbett, an urban designer at Sutton Coldfield-based company Transforming Cities.

Mr Corbett said Victorian Birmingham had been "sacrificed to the concrete collar of the ring road"

"By not having one continuous tunnel, you have a gap you can do nothing with and it makes it very difficult for pedestrians to cross over to the other side of the ring road.

"It means you split the city centre in two and makes it almost impossible for people to walk from the Colmore business district to the Jewellery Quarter."

In 1988, some of the world's greatest architects and designers met in Birmingham to come up with something called the Highbury Initiative to help pull the city out of its economic gloom.

It was felt that in the recession, and following the demise of many of the city's car manufacturers, Birmingham had to reinvent itself and become a place people would want to visit.

Plans included turning the traffic island in front of the Council House into a pedestrianised public square and creating Centenary Square and Brindley Place.

"We need something like that again and to look at the long-term, not just solutions for the here and now," Mr Corbett said.

"We have to look at whether it would be best to just have one long tunnel and create more public squares on top of that."

'View over the A38'

But redeveloping Birmingham would be much more complicated and costly than just dealing with the concrete tunnels, said Dr Nicole Metje, a civil engineering expert at the University of Birmingham.

"The problem is not the tunnels per se," she said.

"If you want a city that focuses on the experience for pedestrians, just looking at the tunnels won't solve the problem. There are lots of other major roads and the only way you get round that is by putting everything underground.

"For instance, if you want to walk from the Bullring to the Mailbox, you have to cross several roads, walk under an underpass and if you decide to sit outside a cafe on your way over, you'd probably sit next to a busy road and have a view over the A38.

"Birmingham was a city built to accommodate the car and it's not easy to get away from that."

City council leader Sir Albert Bore has said he would not rule out looking at more radical changes to the tunnels in the future,

However, the authority said it was currently just focused on the next weeks' work and "keeping the city running".

"In this age of austerity, every pound spent on Birmingham's roads needs looking at and we need to examine how it helps the city to become a more pleasant place," said Mr Corbett.

"But if that question had been asked in the 1960s, the tunnels and the ring road would never have been built and Birmingham would still have a beautiful Victorian city centre, all of which was sacrificed to the concrete collar of the ring road."

- Published22 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published20 July 2013