What to do with an ancient skull and head collection?

- Published

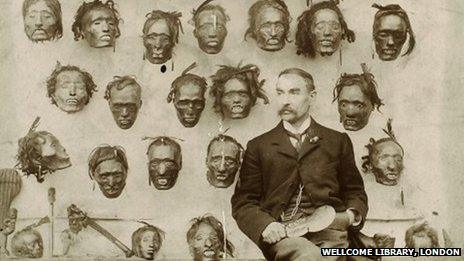

Collectors of tattooed or shrunken tribal heads sometimes donated items to museums and academic institutions as they were founded

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, which has a sacred Maori area, sent a delegation to collect the Maori head and skulls

Jonathan Reinarz, from the university's History of Medicine Unit, said models are displayed where human remains would once have been exhibited

Mummified heads, tattooed skulls and relics of sacrifices are among the collection of about 60 ancient body parts that the University of Birmingham no longer wants in its stores. But what do you do with an ancient skull and head collection of potentially culturally sensitive artefacts?

After returning a Maori tattooed head and skulls to New Zealand, university staff revealed the institute is facing the problem of what to do with other ancient remains identified in the medical school stores.

Dr June Jones, religious and cultural diversity expert at the university, said the remains reflect European exploration and the former British Empire.

'Deeply ashamed'

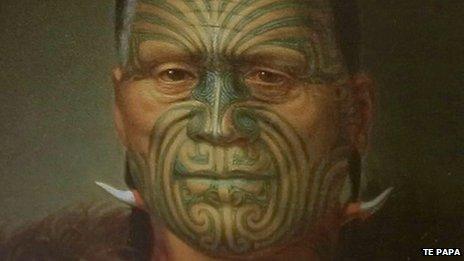

A mask of a Maori tattooed head, similar to one returned by Birmingham University, is on display in Warrington

Each item is boxed and labelled with a location, including Fiji, East Africa, Australia, the USA and New Zealand. Some are simply classified 'Inca'.

The fact is the university would rather not own this material at all.

There is scant paperwork about how the body parts came to be in Birmingham, but it is likely they were collected by wealthy individuals in the 1700s and 1800s before being donated to the medical school, which was founded in 1825.

"To keep them would be wrong," said Dr Jones.

"These items being stolen or traded is an example of historical practices we're now deeply ashamed of," she added.

The collection is made up mostly of skulls. Some of them show marks that suggest they have been used for phrenology, a practice popular in the 19th Century that tried to prove links between head shape and character.

Others are misshapen, which the university suspects were children selected for sacrifice whose heads were bound from birth to produce unusual deformities.

The university still receives enquiries from donors wishing to help the anatomy department after their death, but it does not use ancient remains for teaching or display.

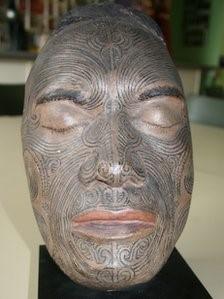

Dr Jones recently instigated the repatriation of a tattooed Maori head and skeletal remains to New Zealand. Inviting Maori delegates from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa to collect the artefacts - their ancestors - was the culmination of more than two years' research work.

Arapata Hakiwai, the Maori leader of the museum, said: "Repatriation is always very special, it's the return of our ancestors home."

Dr Jones has also returned one set of skulls herself, carried as luggage with special permission, on a flight to California.

She said: "I spent most of the day crying. It's a huge responsibility looking after these things. It is almost like carrying a baby and giving it back to its mum.

"They are so much more than bones to the tribes, they are getting their heritage back."

Dr June Jones and the boxed skulls were received by John Burch, Salinan Tribe Traditional Lead

Roseanna Maxwell, a member of the Salinan tribe present at the Californian repatriation, said: "Words cannot express the depth of gratitude owed to Birmingham University.

"This shows other universities, museums and private collectors how to take a look in their own closets and repatriate to culturally affiliated tribes."

Jonathan Reinarz, from the History of Medicine Unit at the university, said: "We have to take responsibility for this. This is not our past, this is in front of us now.

"Repatriating material shows recognition for tribal people and their rights, it underlines how they need to be seen."

The New Zealand government has been proactive in researching Maori remains and has archives suggesting more than 400 are still held in the UK alone.

At one stage Aberdeen University claimed to own about 80,000 Maori exhibits. Some of these were returned in 2006, when Neil Curtis, the curator of the university's Marischal Museum, said: "They are no longer objects, they are people."

Oxford University continues to display some of its tribal remains publically, in the Pitt Rivers Museum.

It has a policy of assessing education and research significance before remains are considered for repatriation.

Birmingham University is now planning to return skulls to Australia, despite having limited details of where they originated.

The Maori remains from Birmingham University were received in a formal ceremony in New Zealand

"DNA testing is expensive, at £300 a sample, and because these skulls are so old there's no guarantee of a good result," said Dr Jones.

Instead, archives have been studied and information sought from indigenous leaders.

A decision will be made by the end of the year on whether to invite indigenous representatives to Birmingham or to send Dr Jones to Australia with the remains.

The rest of the collection has a less certain future because there is so little evidence about its past.

Many countries visited by collectors do not have official repatriation programmes or the resources to undertake research.

Where no provenance and rightful owner can be found, the university admits it may have to "sensitively destroy" remains by cremation. For now, though, the team's research continues.

- Published18 October 2013

- Published8 October 2013

- Published8 August 2013

- Published25 May 2013