Moving day at the zoo: How do parks transfer their animals?

- Published

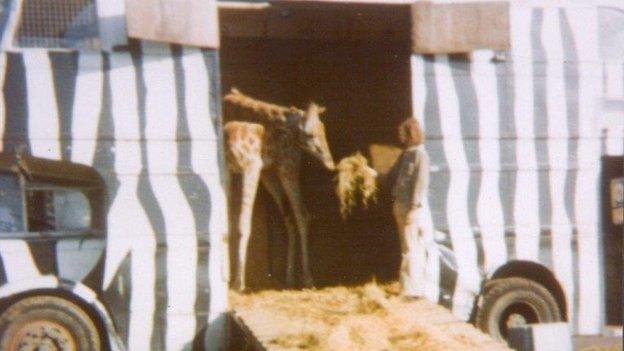

Rufus, a male giraffe, arrives at West Midlands Safari Park. He is part of a programme to start a new breeding herd

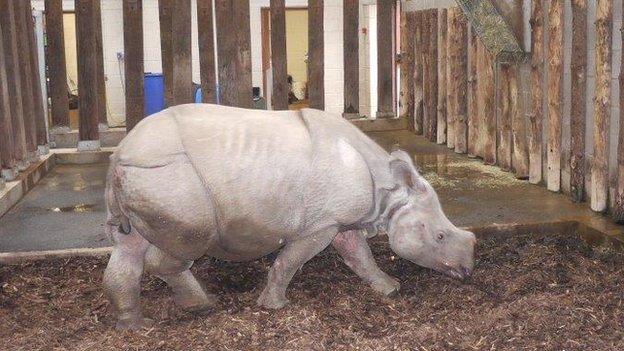

Sunanda the rhino is transferred into her new home

As the transfer of a rare Sumatran tiger into Dudley Zoo last month proved, zoos and safari are often very creative when moving their animals from A to B. BBC News Online finds out how keepers coax new arrivals into their surroundings.

For Nelly the elephant it was, apparently, all so simple. She packed her trunk and off she went.

But transporting animals between zoos and safari parks around the world tends to require rather more forethought.

The tricky transfer of a rare Sumatran tiger to Dudley Zoo last month is one example of the meticulous planning many such operations require.

After travelling from Krefeld Zoo in Germany, 20-month-old Joao was lifted into his enclosure by crane.

"Moving house is said to the one of the most stressful things a human can do, so the same is probably true of animals," said Bob Lawrence, director of wildlife at West Midlands Safari Park.

It is his job to make the transfer of animals to the park at Bewdley, Worcestershire, which holds more than 160 exotic species, as smooth as possible.

Comfortable and familiar

Planning for new arrivals starts months before their arrival, he said.

"There is a lot of paperwork these days and tests to make sure the animals are fit and aren't going to carry any diseases into the country.

"Then, about a month before they arrive, we go and visit them at the zoo.

"The more we can understand about how they are kept and managed, the easier it should be for them to transfer to new surroundings."

This year, the park's new residents have included three giraffes, a dhole - a species of wild dog - from Germany and a night monkey from Switzerland.

The most recent arrival was an Indian one-horned rhino called Sunanda who came from Amersfoort Zoo in Holland.

About three weeks before Sunanda arrived, her transport box was delivered to her Dutch quarters.

She was fed in her box every day, which Mr Lawrence says allowed her to feel comfortable and familiar inside it.

On moving day, she was transferred to a lorry and travelled to Harwich by ferry.

Once, parks had all sorts of ways of getting animals into their new homes. This giraffe arrived at West Midlands Safari Park on a double decker bus

Modern vehicles are purpose-built for transporting animals and come equipped with temperature regulation and CCTV

"Most animals sit down and go to sleep during the journey," said Mr Lawrence.

"Rhinos just eat non-stop. They like to eat carrots. As long as they have plenty of fruit and vegetables, they are happy."

At the end of her 460 mile (740 km) journey, Sunanda was brought into her new quarters. More food was used to tempt her out into her new home.

Her first glimpse of her fellow rhinos was through a partition, but they were soon allowed to join each other.

"She has to be in isolation for 30 days as a veterinary precaution but we isolate the whole group rather than just one rhino on their own," said Mr Lawrence. "She's quite sociable and we can feed her by hand."

'Smell was horrendous'

In the 40 years Mr Lawrence has worked at the park, he has seen the transfer process change considerably.

He said: "In the early days, we had all sorts of ways of moving our animals. Once we brought a giraffe here on a double decker bus.

"Now we use specialist vehicles with heating and sat nav."

Now, he said, most animal movement in Europe is coordinated by an international breeding programme - the European Endangered Species Programme.

"This is a programme that monitors which animals are best mated," he said. "It looks at zoos and parks that belong to the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria."

Most animals are transferred from other zoos and parks, rather than the wild. In the past, animals could come from Africa by boat but now the European Union limits the number of inspection posts for animals to airports only.

"They have to come by air, which limits the size of animals we can bring," said Mr Lawrence. "The most I have ever managed to get on to a plane has been 10 rhinos, the crew and me. The smell was horrendous."

Such changes have made the transition much smoother for animals - in fact, so settled do some of them become in their crates, the park staff have had difficulty coaxing them out.

"About eight years ago, we had brought three white rhinos from Africa," he said. "Nobody could get them out of the crate. Then I noticed they pricked up their ears when a guy with a South African accent went past. I tried talking to them in the tiny amount of Afrikaans I know, and all three of them got up and walked out of the crate."

Members of the public rarely know an animal was being transported on the motorway next to them

Most of the transfers happen quietly and efficiently.

"Members of the public would rarely even know an animal is in transit," said John Partridge, senior curator of animals at Bristol Zoo.

"You could be driving along the motorway and an animal such as a lion could be being transported at the same time."

Animal moves can vary in scale from tiny, delicate invertebrates, such as butterfly pupae, to large and dangerous animals including lions or gorillas.

Recent arrivals at Bristol have included an adult male Asiatic lion from Twycross Zoo, which keepers drove down the M5 in a vehicle housing a purpose-built crate, three giant tortoises weighing up to 25 stone each and a male red panda called Sir Ed who was flown over from New Zealand as a genetic match for the Zoo's female panda, Jasmina.

"We have our own vehicles, crates, carrier systems and strict protocols in place to ensure it is done in the best possible way," said Mr Partridge. "Animal moves are always taken very seriously but it is something we do fairly regularly."

Zoos and parks are united in their belief that animal moves have an important rationale behind them.

"We have Indian rhinos, white rhinos and African hunting dogs here," said Mr Lawrence. "They are all endangered - some critically so. Many are disappearing off the face of the earth at an alarming rate.

"Parks and zoos are very good at working together to make these important animal transfers take place successfully to the benefit of the species involved."

- Published14 November 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published27 June 2013