Birmingham's proud trophy-making history

- Published

The All England Lawn Tennis Club paid 100 guineas for the men's singles champion trophy, which was made by a Birmingham firm of silversmiths

The Wimbledon men's and ladies' singles trophies were both made in Birmingham in the 19th Century, but what other trophies were created in the city's famous Jewellery Quarter?

As sporting events became increasingly popular and rich during the latter half of the 19th Century it became common to award grand and expensive trophies to the victors.

Birmingham, as home to many of the best gold and silversmiths in the country, quickly became a leading player in the development of the sporting trophy and still maintains a prominent position today.

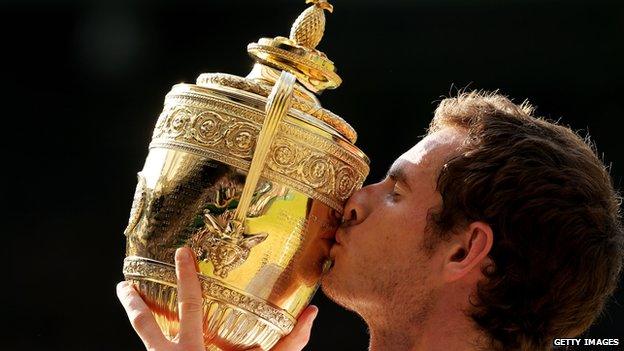

Wimbledon trophies

When the winners of the men's and ladies' singles hold their trophies aloft on Centre Court at the All England Club this year, they will have silverware made in Birmingham in their hands.

Both the men's trophy and the ladies' Championship Plate, also known as the Rosewater Dish, were made by the city's silversmiths Elkington and Co.

The Wimbledon Ladies Singles trophy is a copy of a Huguenot pewter dish in the Louvre known as the Temperentia dish, designed by Francois Briort in the 1580s.

The company was founded in the 1830s and at its peak employed more than 2,500 workers at its factory in the Jewellery Quarter.

"In the 19th Century if you needed a trophy made you went to Elkington and Co," said Craig O'Donnell, a valuer and curator at the Birmingham Assay Office.

The company was known as "the best quality silversmith in Birmingham" with so many super-rich clients that it could afford not to "skimp on the quality of the metal", he added.

Elkington and Co perfected a process known as electroforming, which uses an electrical current to coat a mould with silver. This process was used to create the Wimbledon Rosewater dish in 1864.

The trophy is a mixture of silver and silver-gilt (silver coated with gold) and is a copy of a French dish in known as the Temperentia held in the Louvre. It depicts the four elements surrounded by seven arts - astrology, geometry, arithmetic, music, rhetoric, dialetic and grammar.

A copy was made of the original and then electroforming was used to build it up layer by layer in a process that took several months to complete.

The trophy was well received and the firm was called on again years later when the All England Tennis Club needed a new men's trophy, the previous two having both been given to William Renshaw when he twice won the tournament three times in succession.

The cup was made in a classical style with two handles and is highly decorated with floral work, winged helmets beneath the handles and a pineapple sitting on top.

Less is known about the making of this trophy, but the hallmark indicates it was made in 1883 before being purchased by the All England Lawn Tennis club for 100 guineas in 1886.

However, despite the wealth and glamour of its glory days, as silverware went out of fashion in the 20th Century the firm's fortunes declined. It was taken over in 1963 and its factory in the Jewellery Quarter closed down and was later demolished.

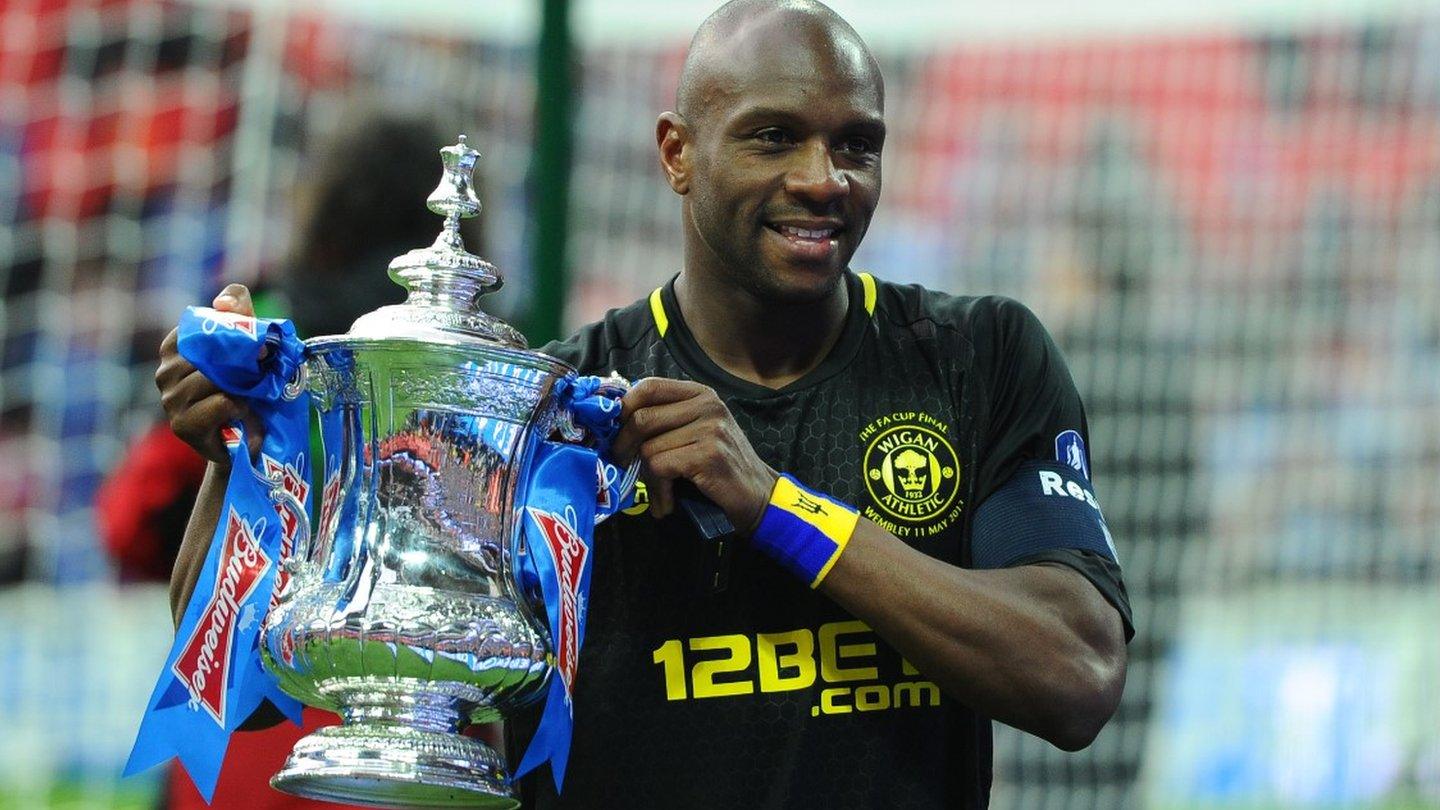

FA Cup

Birmingham's trophy-making expertise was called upon again in 1895 when one of the city's football clubs, Aston Villa, managed to lose the FA Cup trophy.

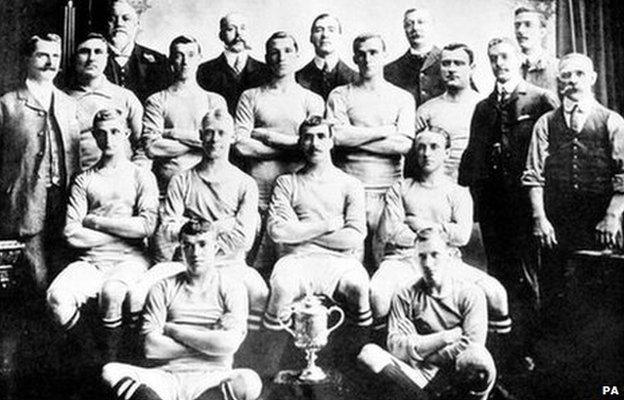

Manchester City in 1904 with FA Cup made in Birmingham

The team had won the trophy and were proudly displaying it in a shop window but burglars broke in and stole it.

The FA ordered the club to fund a replacement and they turned to another Jewellery Quarter firm, P Vaughton and Sons, to make an exact replica of the stolen trophy.

Fortunately, three years previously, the company had taken a plaster cast of the trophy in order to make a miniature for Wolverhampton Wanderers.

The Birmingham-made FA Cup remained in service until 1910, when it was presented to the President of the Football Association Lord Kinnaird and replaced with a trophy made in Bradford. It is now on display at the National Football Museum in Manchester.

However, Vaughton's still makes medals for the Football League at its new base in the Jewellery Quarter and maintains a collection of the medals it made for the 1908 London Olympics.

Vaughton's "gothic works" in Birmingham's Jewellery Quarter still stands today

Premier League medals

Vaughton and Sons have also made the Premier League's winners medals for about 20 years.

Manchester United with their Premier League medals in 2013

They are made of silver and then gold-plated with the league's lion motif.

Although the design looks simple, the firm's managing director Steve Hobbis said they were difficult to make because of a number of little details such as the marks around the edge representing the 20 teams in the league.

Mr Hobbis said his company won the contract because of its reputation as a medal-making specialist.

Olympic torch

Another big commission for Birmingham craftsmen was the torch for the 1948 Olympic games in London.

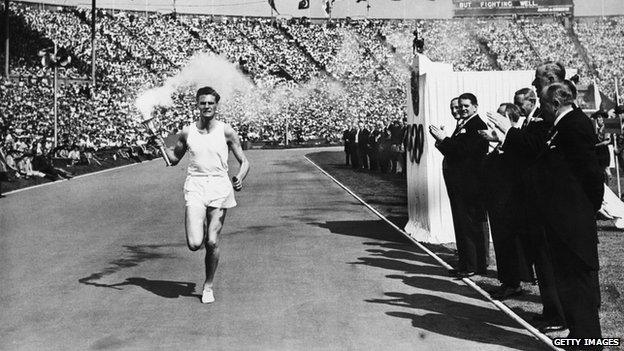

British athlete John Mark carries the Birmingham-made Olympic torch into Wembley Stadium at the opening ceremony of the 1948 Olympic Games

It was created by a Birmingham designer, Bernard Cuzner, and made in the city by Stanley Morris for London's Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, which has the torch in its collection today.

The silver torch has octagonal sides decorated by oak leaves, acorns and rose briars and crowned leopards heads decorate the top.

It was very different from the 2012 Olympic torches, which were made by a Coventry firm and cut from aluminium sheets using machines and lasers.

Those technologies did not exist in 1948, when many trophies were still engraved by hand if they could not be electroformed.

Lonsdale belts

The Lonsdale champion belts given to British boxing champions are made in the Jewellery Quarter by Thomas Fattorini Ltd.

The Lonsdale Belt is awarded to British boxing champions like Carl Froch

They were first introduced in 1909 by Hugh Lowther, the 5th Earl of Lonsdale, and are created using a complicated process which can take several weeks.

First the individual parts are die stamped from silver before being machined and hand finished.

Fattorini said the pieces were then attached to the main centre panel, which holds the large, hand-painted enamel portrait of Lord Lonsdale and two smaller painted panels.

The enamel work has to be fired in an oven and because the different colours need to be heated at different temperatures this needs to be done in stages over several days or weeks.

Finally, the craftsmen polish the metalwork and plate it in 24ct gold before attaching the red, white and blue ribbons.

- Attribution

- Published7 July 2013

- Attribution

- Published6 July 2013

- Published15 May 2014