Birmingham's Central Library: What else could it have been used for?

- Published

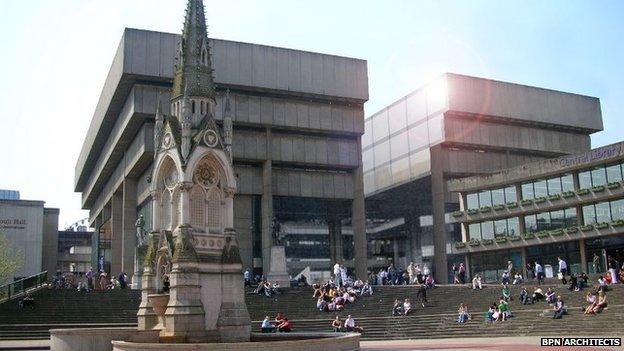

Birmingham Central Library was designed by Birmingham-born architect John Madin

The controversial demolition of Birmingham's Central Library begins on Monday. But while the city council considers the building to have served its time, those who fought to save the library had plenty of ideas for how it could be used in the future.

The shadow of the wrecking balls looms large over Birmingham's Central Library.

But as the demolition crews move in on architect John Madin's 1974 centrepiece - now replaced by a £189m successor - some in the city are looking on with thoughts of what might have been.

An impassioned campaign to save the building has been running ever since plans for the library's destruction were first announced.

Prime Minister Harold Wilson officially opened the library in January 1974

"It's an iconic building and nothing like it will be seen again, if it goes," said Alan Clawley, secretary of the Friends of the Birmingham Central Library, which has been at the heart of the drive to save it.

"It is very wasteful to knock down a building that's only 40 years old."

During its campaign, the Friends canvassed people from all over Birmingham about possible alternative uses for the brutalist book bank.

Here are some of the ideas suggested - but ultimately rejected.

A Birmingham Tate Gallery

Campaigners thought the building's atrium could provide an exhibition space similar to the Tate Modern

With four galleries - including two in London, one in Liverpool and one in St Ives - all in innovatively-designed buildings, the Tate group seemed potentially perfect occupants of the Madin site - provided they were seeking a new home in the Midlands, that is.

"We didn't see any reason why Birmingham shouldn't have a Tate and we thought the library would be an excellent location," said Mr Clawley.

"The atrium in the building is very high and would make a great exhibition space - similar to that in the Tate Modern."

But the impassioned appeal to the arts community fell on deaf ears.

"We have no plans to open any further Tate galleries," a Tate representative told the BBC.

The home of an English Parliament

Could English MPs have been persuaded to move to Birmingham Library?

Sarah Bryant, a student at the Cardiff School of Architecture, suggested the library's huge atrium could become a semi-circular debating chamber surrounded by public viewing galleries and rooms for elected members.

"The imagination of students like Sarah shows the capability of the building and how adaptable it is," said Mr Clawley.

"It has a dignity and presence similar to the parliamentary buildings in Scotland and Wales."

Student Sarah Bryant's design for the building

The idea, perhaps unsurprisingly, drew support from the Campaign for an English Parliament.

Spokesman Eddie Bone said: "If the people wanted an English Parliament to be based in Birmingham, why wouldn't it be?"

"If there were an existing building that were suitable, that would be a huge saving, and Birmingham is a very central location in England.

"It would be a very, very exciting opportunity for the people of Birmingham."

Campaigners say converting an existing building into the home of an English parliament could have been 'a huge saving'

However, the cabinet office was less enthusiastic.

"There are no plans for an English parliament in Birmingham Library or anywhere else under the current government," said a representative.

"The devolution question is something that is still under discussion.

"From the government's point of view, we couldn't comment on the site of something we are not planning to build."

A (very costly) climbing wall?

Climbers in the city were enthusiastic about the idea putting a wall inside the library but thought it may not be financially viable

"Birmingham is a long way from the mountains but we know climbing is popular in the city," said Mr Clawley.

"The library's atrium has got the height that could be utilised for a climbing wall. The whole building is like an overhanging cliff - it would be a massive challenge."

Birmingham's Redpoint Climbing Centre was excited by the idea but conceded it may not be financially practical.

"It would be incredible," a representative said. "But as good as it would be to have a climbing wall in the city centre, I don't know if it would make enough to support the site.

"Walls tend to be set up by groups of climbers who want to make a job out of their hobby. They tend to set them up in old warehouses or factories on the edge of cities.

"To own a building in the middle of the city would cost an absolute fortune."

A museum of Birmingham

Should the library have played host to a museum about Birmingham's history - and its music?

Birmingham already has a city centre museum and art gallery.

"The Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery is a well-established museum but we are aware a lot of items have been stowed away in a warehouse in Nechells because the city's museums don't have the space to display this at the moment," said Mr Clawley.

"If you go there, you find sculptures, old buses, telephones - it's amazing.

Campaigners say many treasures are kept in storage because the city does not have the space to display them

"We would also be keen to display something about Birmingham's heavy metal heritage. Birmingham Museum ran an exhibition called 'Home of Metal' recently - it would be great if something like that could be made permanent."

However, it is not known how much traction the idea has with the city's culture bosses. Birmingham's museums did not comment on the possibility of opening a new venue.

They described the treasures, stored in a warehouse, are "amazing"

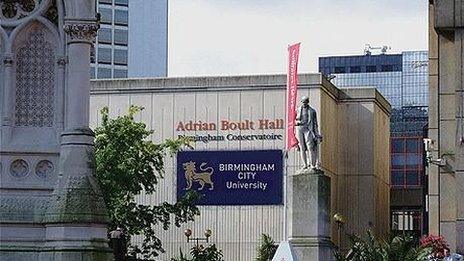

A Birmingham Conservatoire extension

Campaigners say the library would have made a "lively cultural venue"

The library is not the only building that is being lost in the Paradise redevelopment.

The 150-year-old home of the Birmingham Conservatoire is also set to be demolished to build a four-star hotel and shops.

The Conservatoire itself is moving to a new site on Jennens Road in 2017.

But the library campaigners say the building - which is next to the Conservatoire site - would have made an ideal extension.

"It could have been a bit like the Barbican in London - a lively cultural venue," said Mr Clawley.

Professor David Saint, the Conservatoire's principal, said the school had outgrown its current site, after seeing a huge expansion in international students.

"I remember dreaming about whether the old library would have been a suitable venue but I rather suspect the Conservatoire is too much of a specialist construction," he said.

"Every room needs to be acoustically isolated, so somebody practising an instrument in one room isn't disturbed by somebody in another room.

"Converting an old building into something that can meet that spec is difficult."

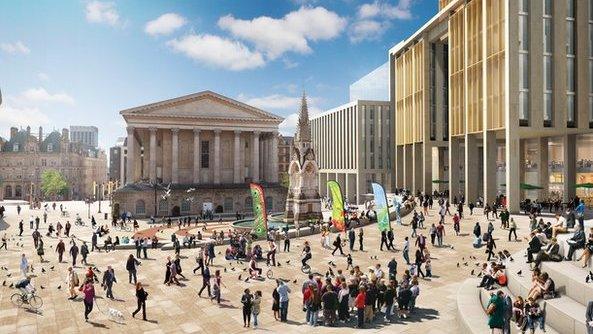

A 21st Century Trade Centre

BPN Architects proposed 'slicing through the building' to make it 'more inviting'

Earlier this year, Birmingham Civic Society ran a competition called Re-imagine, which called for design ideas for buildings considered at risk.

BPN Architects came second with its idea for turning the old library into a trade centre, complete with small workshops and retail outlets.

"Our proposal was to encourage independent creative enterprises to accommodate the building," said Gavin Orton, an associate at BPN.

"We proposed 'slicing' through the building to make it more inviting and draw people through."

"Once people started thinking about the future of the building, all sorts of ideas came out," said Mr Clawley. "But the city council were never interested in them."

Birmingham City Council told the BBC the demolition was "essential" in order to develop the area.

"It was never a question of alternative uses," said a representative.

- Published15 December 2014

- Published25 March 2014