The hidden crisis in rural schools

- Published

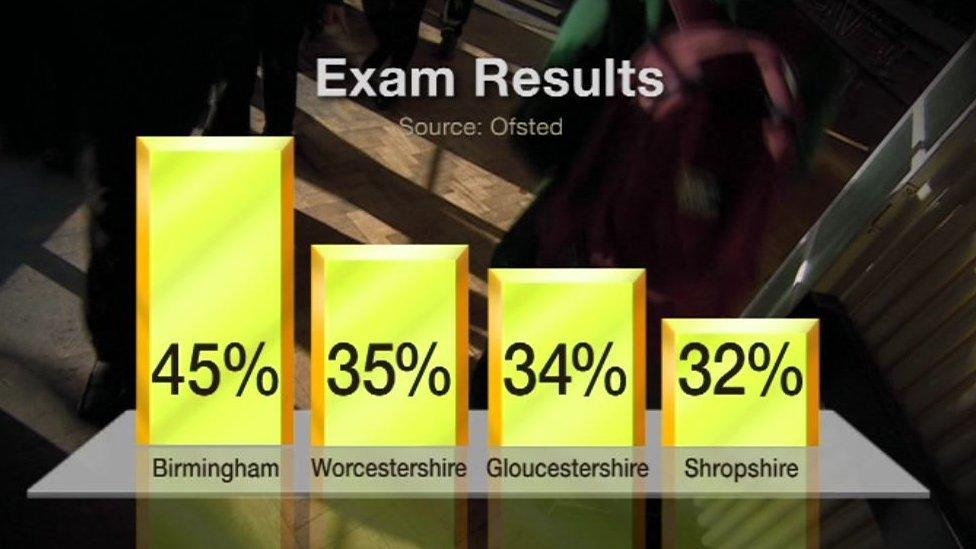

GSCE Schools in central Birmingham are working with disadvantaged pupils better than in rural areas

There's a hidden crisis in our education system and it affects our poorest and most vulnerable kids.

If you come from a disadvantaged background then your exam results depend on where you live.

Disadvantaged pupils are usually defined as those who are on free school meals or who have experience of foster care.

In too many rural schools your education will be significantly worse than if you went to school in central Birmingham.

Actually, for a hidden crisis it's one that crops up quite a lot when I talk to people who work in education. it just doesn't seem to be an issue that's seen as a major national problem.

So we wanted to try and do some research and actually comb through the pages of school statistics from Ofsted to see just how big this gap between town and country is.

The results shocked me.

Our statistics show 45% of disadvantaged pupils obtain five GCSE's, including English and Maths, in Birmingham.

In Worcestershire that falls to 35%, Gloucestershire 34%, Shropshire just 32%.

When I talked to Lorna Fitzjohn from Ofsted she said: "Shropshire is one of the worst performing local authorities in the country for the performance of disadvantaged children."

Pupils at The Community College in Bishop's Castle are encouraged to 'look beyond the hills'

This is a problem specific to pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds. When we looked at the exam results for the pupils from non-disadvantaged backgrounds we found the situation reversed. Rural schools do slightly better than Birmingham and in general are above the national average for exam results.

If rural schools did the same job as urban schools when educating disadvantaged children you'd change thousands of lives.

I've spent the past few months investigating this gap and trying to find out what the problem is. Rural schools do face difficulties that inner city schools do not. In education today there's a huge emphasis on sharing best practice peer-to-peer for example and that's hard to do if your nearest school is 15 miles away.

It's also a question of numbers. A school in the centre of Birmingham might have 50% of students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

These pupils get plenty of focus because they will have a large impact on the school's results. There are fewer disadvantaged pupils in rural schools so it's all too easy for them to drift through their education before leaving at the earliest opportunity. And since there are fewer of them a school's results are pretty much unaffected by how they do in exams.

I visited one rural school praised by Ofsted for rapidly closing this gap between the disadvantaged children and the rest of the pupils.

The Community College in Bishop's Castle in Shropshire is a school where everyone works together to do the very best for all pupils.

On "Aspiration Friday" the timetable is thrown out and pupils are given the chance to explore all sorts of activities from sport and drama to interior design and horse riding.

Headteacher Alan Doust explained to me this is one of many initiatives to help pupils "look beyond the hills".

It's an approach that involves teachers, support staff, parents and the wider community. It benefits all the kids but it's really good for the disadvantaged pupils. It boosts aspiration, attainment and exam results.

So closing this gap is something rural schools can achieve but even a good school like The Community College is reaching the limit of what it can do.

Rural schools get a thinner slice of the funding pie than their urban counterparts. As a country we have been focused on improving the lot of disadvantaged pupils in inner city schools, especially in London. That's worked but it has come at a cost. Disadvantaged pupils in the rest of the country have been largely forgotten about.

As I said at the start these pupils and their problems form a hidden crisis.

Slipping through the school system and disappearing at the first opportunity. A fairer share of funding would certainly help, but the first step is to shine some light on this issue in the first place.