Lisa Potts: Injured nurse 'forgives' Wolverhampton machete attacker

- Published

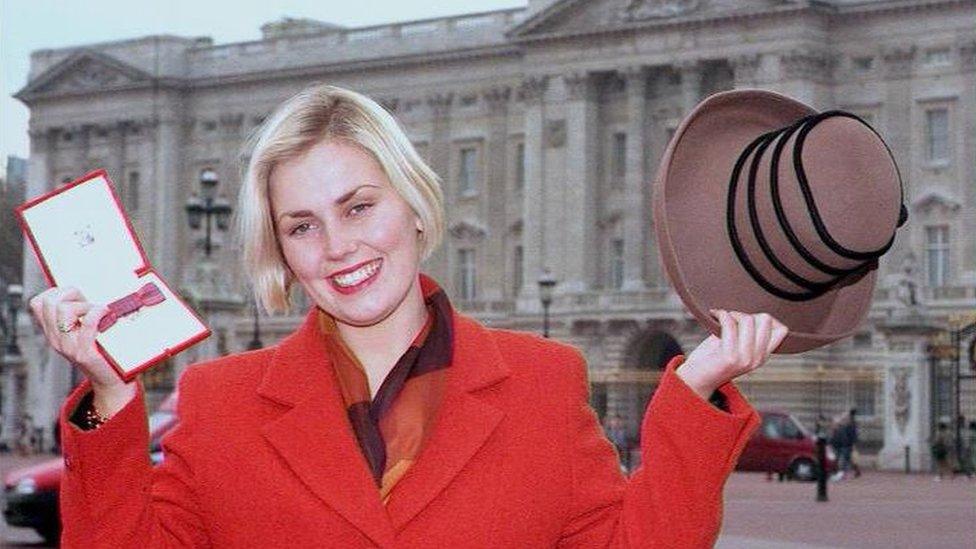

Lisa Potts received several bravery awards

It is 20 years since a machete-wielding attacker stormed into St Luke's Infant School in Wolverhampton, slashing at young children and nursery nurse Lisa Potts.

The youngsters were inches from tragedy - only saved by the quick-thinking 21-year-old's decision to hide them under her long skirt.

As Horrett Campbell was detained by a judge indefinitely in a secure hospital five months later, a tearful Ms Potts told the BBC she could never forgive him for inflicting the injuries on her pupils.

Two decades on, and now a married mother of two boys, aged nine and 12, she feels differently about a crime that shocked the nation.

More recollections of nursery attack: "I often think about him"

"I've forgiven him now for what he did. I had to move on," she says.

"I never had any hate, even in my darkest moments, when I had to relearn everything (because of my injuries). I wasn't angry at him.

"As time went on, I felt sorry for him. I've learned a lot about mental health over the years and I feel sad that he went unnoticed in the community and didn't get help or treatment."

Ms Potts has replayed the events of 8 July, 1996, in her mind countless times.

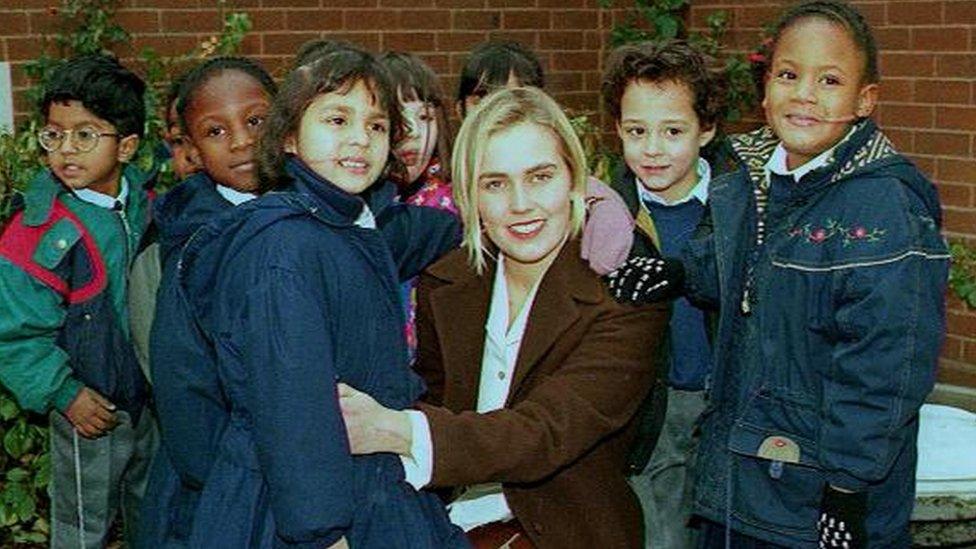

Lisa Potts became an overnight celebrity after emerging as the heroine of the attack at St Luke's School

She and her class of three and four-year-olds were enjoying a teddy bears' picnic in the grounds of the school in the Blakenhall area of the city when Campbell struck.

A paranoid schizophrenic who had been planning his attack for two months, he attacked three mothers waiting outside the school before entering the grounds and threatening the children with his knife.

He slashed Ms Pott's head, arms and back, but despite her injuries she managed to grab a child under each arm while others cowered under her skirt. Three children were also hurt.

Campbell was found hiding in a nearby block of flats a short while later by police.

Lisa Potts says she can now forgive her attacker, Horrett Campbell, 20 years after she saved her class of young children from him

"It only lasted eight minutes, but it changed the course of my life forever," she says.

"From the moment it happened my life took a different path, one full of media opportunities, dinners and awards. It was crazy."

She became an overnight celebrity and one of the most recognised faces in the country. "I used to joke that I was a professional machete heroine. I was so young and I felt like public property.

"For five years I felt like I was on a merry-go-round. Journalists would camp outside my house. I felt like a goldfish."

In 1997, she received the George Medal for bravery from the Queen. But while she described it as a "great honour" at the time, she now says she hid a lot of her true feelings.

"I felt a lot of guilt. Here I was, getting all these awards after such a horrific experience. There were times when I wanted to run away from it all."

Lisa went back to St Luke's as a nursery nurse but left after suffering with post-traumatic stress disorder. Francesca Quintyne, who suffered a cut to her face, is pictured far right.

Lisa was awarded the George Medal for bravery

Ahmed Malik was the youngest of those injured. Just three years old, he suffered a fractured skull and elbow in the attack. Now 23, he's an electrical engineering graduate and living in Basingstoke, Hampshire.

"The main thing I remember is the aftermath," he says.

"My parents were always being interviewed, cameras were constantly in my house."

He says his parents were cautious not to "wrap him in cotton wool" after the ordeal, and helped him to live a normal life.

"I don't think there were any lasting effects on me," he says. "I don't know if it's linked, but I'm left-handed - it was my right arm that was injured.

"When I read about it, it's strange - it's like it didn't happen. I told some of my friends at university after our last exam. I was like, 'beat that'. They couldn't believe it."

Francesca Quintyne was aged four. Campbell's machete slashed her face, leaving her with a deep scar. She has two metal plates holding her jaw together.

"When I was younger people used to stare at me a lot and ask me what had happened," she says.

"But it's faded a lot now I'm older. I used to hide it, but the older I'm getting I don't notice it so much.

"I don't remember anything from the time - it's like I've deleted it. But I've got a big box of news clippings at home and when I read them, I can't believe it happened."

Now working in mental health with children and adolescents, Ms Quintyne says it has helped her understand what led Campbell to launch his attack.

Lisa has kept in close contact with two of the children she saved, Francesca and Ahmed

"It's given me such an insight into why people do those kinds of things," she says. "I can't fully understand it, but I can reason with him. It's helped me to forgive him."

Ms Potts has stayed close to Ms Quintyne and Mr Malik since their ordeal. The former was one of her bridesmaids when she married police officer Dave Webb in 2002.

"I'm so proud of them, and what they've become," she says. "It's when I see them grown up I realise how much time has gone by.

"I saw Ahmed in Asda the other day and I just gave him a big hug. Seeing them as adults makes you realise that life goes on."

It was having her own children, Alfie, now 12, and Jude, nine, that finally made her come to terms with the gravity of her actions.

"Eight years later when I had Alfie, I started to realise the extent of what happened that day.

Paranoid schizophrenic Horrett Campbell was detained indefinitely in a secure hospital after a judge heard he'd planned the attack for two months

"And I was so upset when he first went to school. Would it happen to him? All these fears came up.

"We've always been really open with the children about what happened right from the start. Alfie used to call my arm 'my hurty'.

"I didn't want to frighten them about going to school. By knowing what happened, they understand life is not always easy. Not just about what happened to me, but Horrett Campbell too."

The attack at St Luke's came four months after the Dunblane massacre, where 16 pupils and a teacher were killed.

The events sparked a transformation in security at schools across the UK, with the government publishing new guidelines for local education authorities and head teachers about how to safeguard their pupils and staff.

Schools identified as "low risk" were advised to reassess visitors' access, limit the number of entrances and install intruder alarms.

"High risk" schools were encouraged to issue staff with personal attack alarms, install CCTV, employ security guards and consider grilles on windows.

As the nation reacted to what happened at St Luke's, Ms Potts - while very much still in the public eye - was trying to overcome post traumatic stress disorder and depression.

She gave up her job as a nursery nurse and turned her attentions to charity work, starting her own organisation Believe to Achieve, helping children in Wolverhampton with low self-esteem to realise their potential.

Lisa says becoming a mother to Alfie and Jude made her realise the magnitude of what she did in 1996

"I thought we'd only be going for about three years but it's been 15 now and we're helping children in Dudley schools now," she says.

"It's great to think that from such a terrible event something so positive happened."

She went on to train as a nurse and is now working as a health visitor, combining her skills as a nursery nurse and her extraordinary life experience to help families.

"It's nice that I can use what happened in a positive way. It's part of my life experience - it's who I am.

"So many things came out of what happened, but the biggest thing was survival.

"Nobody died that day. When you think about Dunblane, we were so lucky."