2011 riots Birmingham: How Tariq Jahan stopped a race riot

- Published

Tariq Jahan's speech has been credited with preventing renewed racial violence in the city

When three Asian men were killed in Birmingham protecting businesses from black looters, many feared the city faced a race riot. Yet a speech by a grieving father is now credited with almost single-handedly bringing the city back from the brink.

In the early hours of 10 August 2011, as looting and disorder ran into a second hot night, about 80 men stood guard outside a petrol station in Dudley Road, Winson Green.

It was a scene repeated outside businesses around the city. Among the crowd were Tariq Jahan and his 19-year-old son Haroon.

At about 01:00 BST, three men were fatally injured in what was described as an orchestrated "chariot charge" of cars.

Tariq Jahan was among those who rushed to give first aid. He tried in vain to revive brothers Shazad Ali and Abdul Musavir before turning to the third man.

It was then that he realised it was his son.

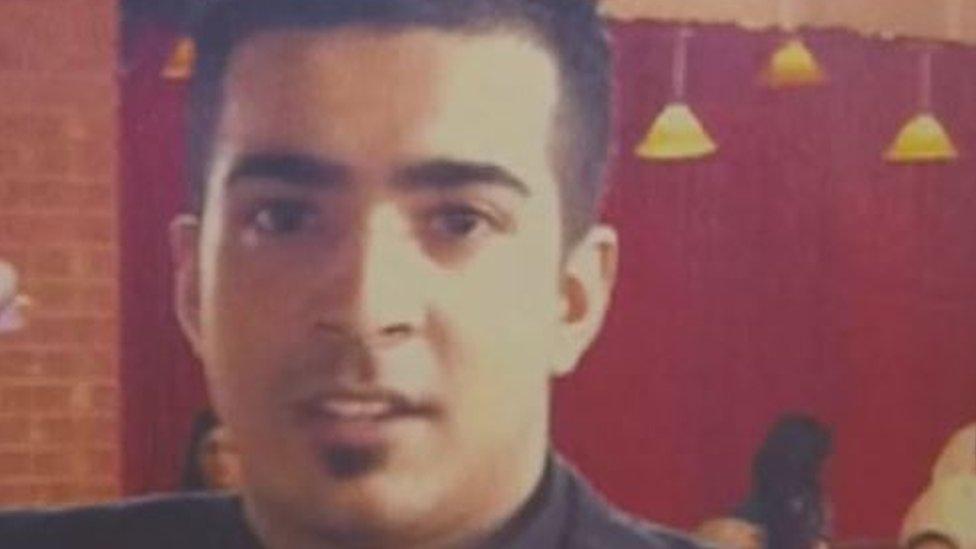

Haroon Jahan was killed when he was hit by a car carrying suspected looters

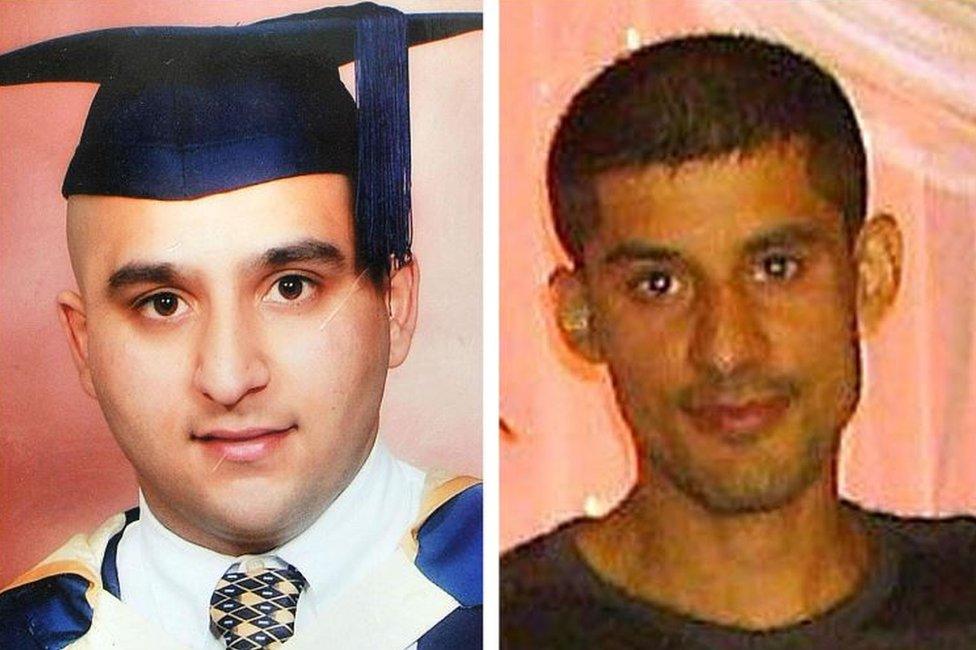

Brothers Shazad Ali and Abdul Musavir also died

"Every time I breathed into Haroon, hot blood was pouring out of his nose," he said. "I knew then he wasn't going to survive.

"I watched the life ebb out of him. My son bled to death in front of my eyes. It is very hard to ever get that memory out of your mind."

Racial tensions in the area had been high for decades. Six years previously, there had been two nights of riots between the city's black and Asian communities in nearby Lozells. A young black man, Isaiah Young-Sam, had been killed.

Now, after the raid on the petrol station, some among the Asian community were openly talking of revenge. The authorities were increasingly fearful that the next night would bring more violence and bloodshed.

Shops windows were smashed, cars burned out and violence ensued in the riots

Concern reached right to the top of the government. Officials from 10 Downing Street summoned community leaders to a crisis meeting at West Midlands Police's headquarters the following day.

One of them was Derrick Campbell, a government adviser and leader among the city's black community.

"There was a real fear that this could trigger a race war," he said. "Gangs were telling us they were tooling up with balaclavas and guns."

Chris Sims, the then chief constable of West Midlands Police, was deeply worried.

"Those who had served in 2005 were fearful that we were getting into that intercommunity violence," he said.

"We did not want to slip back into those terrible events. Who was to say it wasn't going to last months or years?"

History of racial tension

The city's Asian and black communities clashed during riots in 2005

Tension between Asian and black groups had simmered for decades in north Birmingham.

During the Handsworth riots of 1985, Asian businesses were targeted and two brothers, Kassamali and Amirali Moledina,, external died when they were trapped inside their blazing post office.

Then in October 2005, an unsubstantiated rumour of the gang rape of a black teenage girl by a group of Asian men saw petrol-bombs thrown, windows smashed, external and outbreaks of violence.

Innocent bystander, Isaiah Young-Sam, external, was stabbed through the heart and killed.

More than 1,000 extra officers were drafted in from as far away as Scotland to aid the overstretched force.

David Cameron himself arrived in Birmingham at about 15:00 BST. It was quickly agreed a community leader would give a speech calling for calm, in an effort to ease tensions.

"We decided we needed to make a speech but I was not the right person to do it," said Mr Campbell.

"[Mr Cameron] listened to what we wanted to say and encouraged us. We looked towards the families of those killed. Tariq had lost his son but the other father had lost two boys. Tariq was quite a confident guy and known by some of the members of the group."

With time fast running out, the community leaders and senior officers travelled in a police convoy to Mr Jahan's house.

David Cameron with Chief Constable Chris Simms and Assistant Chief Constable Sharon Rowe at West Midlands Police headquarters during the Birmingham 2011 riots

Despite being heartbroken and deep in shock, Mr Jahan had already spent much of the day trying to calm tensions.

"The whole community was up in arms," he said. "Young men had come to me and said 'we want to get revenge'.

"I was in tears. I said 'If it was your son, how much revenge would you want on innocent people?'

"There would have been war between different communities."

Desperate for the violence to end but overwhelmed by grief, Mr Jahan had to be persuaded to speak out.

Gangs of looters targeted businesses around the city

"The speech was one I was going to give but I said 'Tariq your voice is far more powerful'," said Mr Campbell.

"We helped co-write it. It was written and delivered within 45 minutes. We had to act fast - lives were under threat."

At about 19:30 BST, Mr Jahan faced the world's media outside the petrol station where, hours earlier, his son had lain dead in his arms.

With representatives of the city's black, white, Muslim and Sikh communities standing behind him, he read out a statement calling for calm and for communities to unite.

Then, overcome by emotion, he spoke directly from the heart.

Tariq Jahan said community leaders helped to draft his speech but his final and most resonant words were spontaneous as emotion took over

"Basically I lost my son," he told the crowd. "Blacks, Asians, whites - we all live in the same community. Why do we have to kill one another?

"What started these riots? And what's escalated? Why are we doing this? I lost my son. Step forward if you want to lose your sons.

"Otherwise calm down and go home."

Five years later, Mr Jahan admits he was surprised at the impact his words had.

"I don't know where those words at the end came from - they just came out," he said.

"A lot of people said to me 'we can't believe what you said, I don't know where you got the strength'.

"It impacted the public massively. They did walk away."

Flowers were laid in memory of the three men killed at the Jet petrol station on Dudley Road

For Mr Sims, Mr Jahan's words did not only prevent further violence in Birmingham, they helped end the rioting across England.

"He captured the moment," he said.

"The disorder pretty much stopped everywhere, not just in the West Midlands, but even in London. That was just about the end of all the street disturbances.

"Tariq was able to bridge a gap between different communities. He spoke not as a community leader but as a father who lost his son.

"It was carried on every front page across the world."

- Published30 October 2015

- Published10 August 2011