Birmingham homeless volunteer raises 'Cardboard City' fears

- Published

Living rough: 'People walk past you like you're scum'

England's rough sleeping population is rising, according to latest figures. With council budgets under pressure and the need for charity support growing, some volunteers in its second city fear a bleak outlook for those living on the streets.

Birmingham is booming.

One of Europe's fastest growing cities, its rising population is swelled by people moving out of London, attracted by a growing economy and a resurgence in confidence.

Thanks to to developments like the shiny new Grand Central shopping centre and the striking £189m library, the city is said to be enjoying "a period of renaissance", according to the Chamber of Commerce.

But, like every other UK city, there is another area of growth that's not so enthusiastically welcomed: homelessness.

Rough sleeping rises at 'appalling rate'

Why are there so many homeless people in Birmingham?

What are the best ways of helping rough sleepers?

"I always say, you judge a society on how it looks after the weakest members. And I would say this is a third world country because there is no care from the government," says former rough sleeper Corrado Lever.

Former social worker Corrado Lever has had no home for two years

Mr Lever, originally from Torquay, has been without a home for the past two years. He stays in hostels when he can, but also spent a month sleeping rough in the city.

He uses a soup kitchen when he needs to and is about to move into a flat, which he feels will enable him to start applying for jobs.

"There are young people that are homeless, there are old people that are homeless," he adds. "People in their 60s - about my age - can't get work any more and I believe all of that is the government's responsibility.

"Give people dignity. Give them somewhere to live. Give them meaningful employment and you wouldn't get these problems, by and large."

The annual count in autumn 2016 found 55 rough sleepers on the streets of Birmingham, compared with 36 the year before. In 2011, just 7 were counted.

Birmingham's problems are not as great as other areas of the country, but concerns had already been raised about the increased visibility of rough sleepers in the city before the latest rise.

And the death of a rough sleeper in a loading bay in November 2016 - on one of the coldest night's of the year - prompted a huge reaction from people asking what was being done to solve the issue, especially with council funding cuts to support services looming.

Over the next two years, £10m could be cut from the council's £24m Supporting People budget. That is subject to consultation.

The department is responsible for some of the city's most vulnerable: rough sleepers, the disabled, mental health patients, ex-offenders and victims of domestic violence.

Peter Griffiths, cabinet member for housing and homes, told councillors last week that although the authority would be increasing the homeless budget provision by £3m from April 2017 through government grants, the cuts over the next two financial years would have "a significant effect".

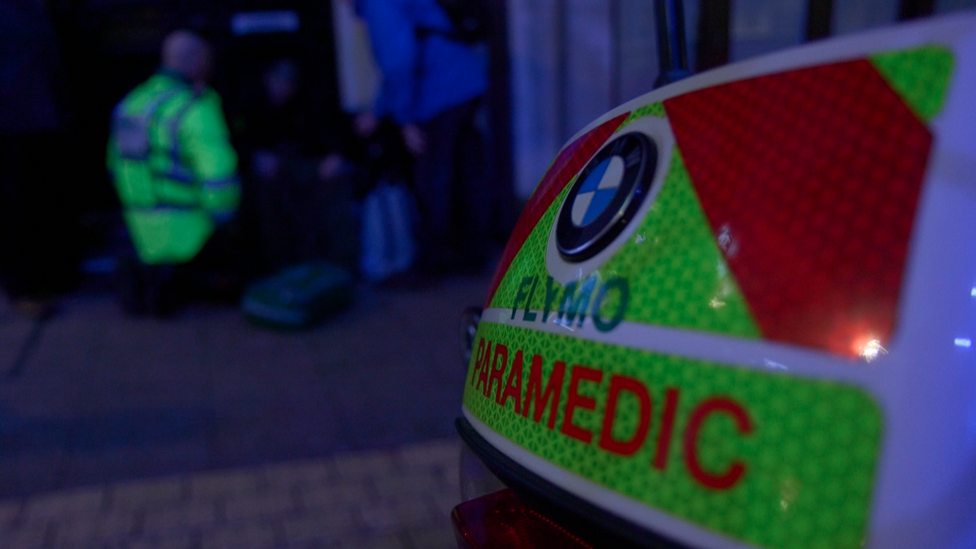

Birmingham Homeless Outreach volunteers provide food, bedding and clothes to those on the streets

Councillor Sharon Thompson, Birmingham City Council's ambassador for homelessness, said: "This is a national crisis and we are working hard with our partners to tackle it as best we can.

"Despite our considerable financial pressures, we commission a wide range of services to support rough sleepers and those facing homelessness - whether young people, victims of domestic abuse, former offenders or entrenched rough sleepers."

Paul Atkin also knows what it's like to live on the streets.

Determined to help others who found themselves in a similar situation, he set up Reachout Network Ministries in 2006. The charity offers a "safe and secure" environment for the homeless in a Methodist church, where rough sleepers can eat and shower.

He also carries out early morning checks on people sleeping on the streets and gives out food and drink two nights a week.

From his experiences and daily checks, Mr Atkin believes the problem in the city is "huge" - and could increase.

A rough sleeper is treated by paramedics after apparently being assaulted

"The numbers have increased through circumstances that people have found themselves in and I think is only going to get worse before it gets better," he says.

"We've another bout of cuts about to come in... that's going to have a massive knock-on effect. Services are so vital and needed at this time.

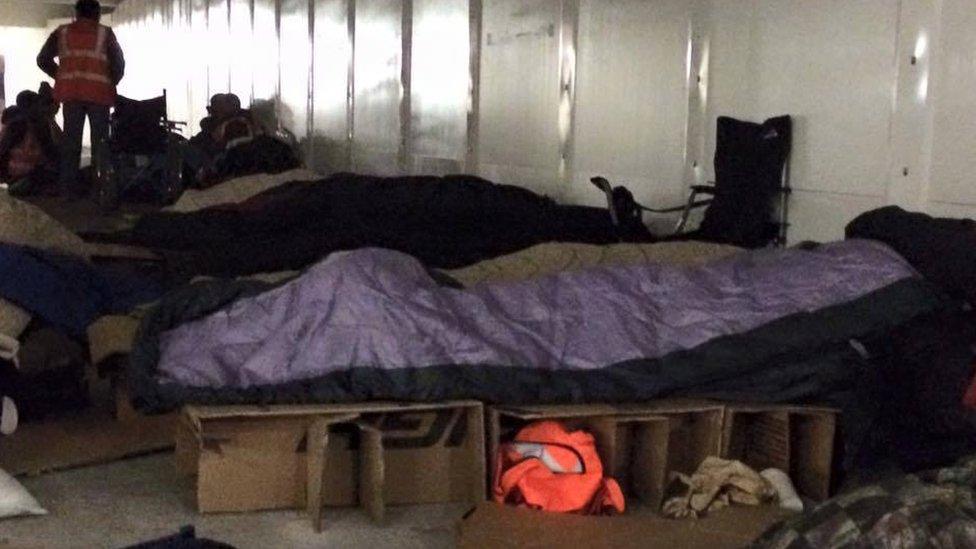

"I think we can only imagine... someone said in the papers the other day it'll be like Cardboard City and I think we're getting there very, very soon. It's shocking."

Cardboard City was the name for a community of as many as 200 people living in the shadow of Waterloo railway station from 1983 into the late 90s.

Lambeth Council won an eviction order in in February 1998 to remove the last few dozen left living in what became a symbol for homelessness in the UK.

Paul Atkin, who used to live on the streets, set up Reachout Network Ministries in Birmingham

Some charities in the city have questioned previous official figures around the number of rough sleepers and homeless, claiming they should be higher.

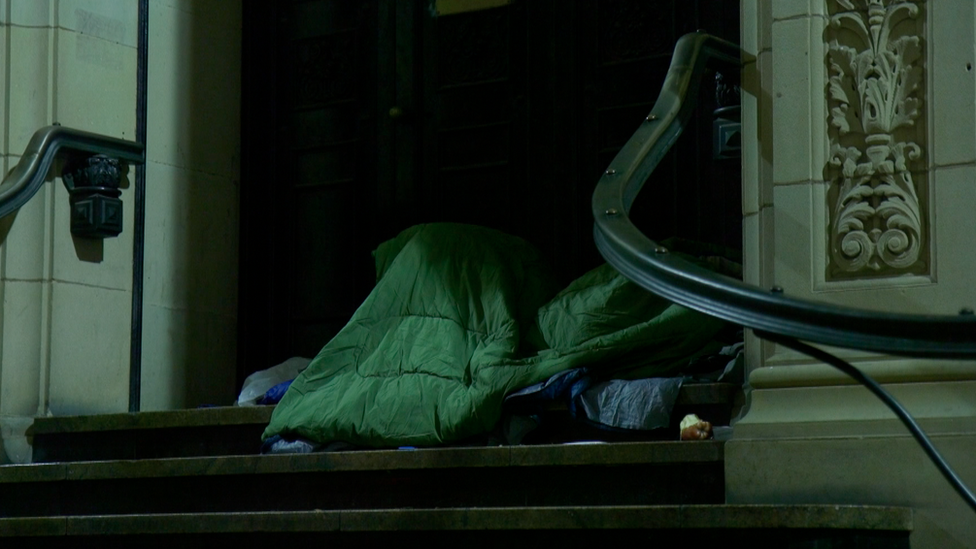

The increased visibility of people sleeping in doorways and back streets, has been attributed by one charity to the 2015 demolition of the city's old derelict library, which provided unofficial shelter for several years.

Rik James, from Birmingham Homeless Outreach, says he fed up to 40 a night under the old library.

The council admits the role of charities and third party groups helping the vulnerable will be even more important when once budget cuts bite.

"We are trying to mitigate the effect by working with third parties," Mr Griffiths told colleagues last week.

Paul Atkins carries out early morning checks on people sleeping in the city

Of the many charities providing help and support, the Let's Feed Brum campaign, pools the resources of 30 restaurants to feed the homeless one night a week with fresh food that would otherwise be thrown away.

The charity is also involved with New Street Soup Kitchen, which operates Monday to Saturday and can serve between 50 to 100 people at one time.

Let's Feed Brum volunteer Hattie d'Souza, who helps dish out meals and drinks, says she wanted to get involved after being "shocked and upset" at what she had seen in Birmingham.

She says the team of volunteers was growing every day and believes it was "all our duty" to help those in need.

"It's really unfair to think that a hot meal, or a hot drink, or a blanket is going make someone want to stay on the streets where it's unsafe. People are horrible to these people," she adds.

Hattie d'Souza said the work she and other volunteers do was vitally important

"People look through these people and when they don't look through them they are often quite cruel - and a hot meal isn't going to change that.

"People are not going to want to stay on the streets and be cold and be hungry and be scared for the sake of getting a free sandwich.

"You come down here... and you might be the first person they've had a smile from that day. And that is sometimes what people need."

Mr Lever says the work being done in the city to help the vulnerable was "brilliant", although he believes some people get to a point where they "actually resent people trying to help".

"It's a matter of pride simply. A matter of self esteem," he says.

"To blame the victim is very wrong and very cruel frankly. Because unless you have been in that situation you can't comment.

"Birmingham has always been the heartland of this country... Birmingham has always been welcoming to immigrants and has a strong sense of community.

"The feeling I get from Birmingham is just let Westminster get on with what it wants to get on with and we'll sort it out in our own community."

Update 26 January 2017: This article was amended to clarify information that the Supporting People Budget could be cut by £15m. The figure is £10m.

- Published25 January 2017

- Published6 December 2016

- Published18 November 2016

- Published21 December 2016