The man keeping the world's lighthouses shining

- Published

Tim Nguyen's team restores lighthouses all over the world

For more than 150 years, glassmakers in one of England's landlocked regions gave light to the seafarers all over the world. It has fallen to one man on the other side of the planet to preserve their legacy.

Shining a fresh light on the forgotten past of the Midlands-based Chance Brothers is Tim Nguyen, who has dedicated himself to restoring their work in 2,000 lighthouses across the globe.

The Australian's quest to restore their optics using original parts and methods is unmatched by anyone.

He has spent 20 years honing his craft and hopes he will soon find a skilled glassblower to complete the team in Melbourne and recreate the traditional techniques used by the original Black Country firm.

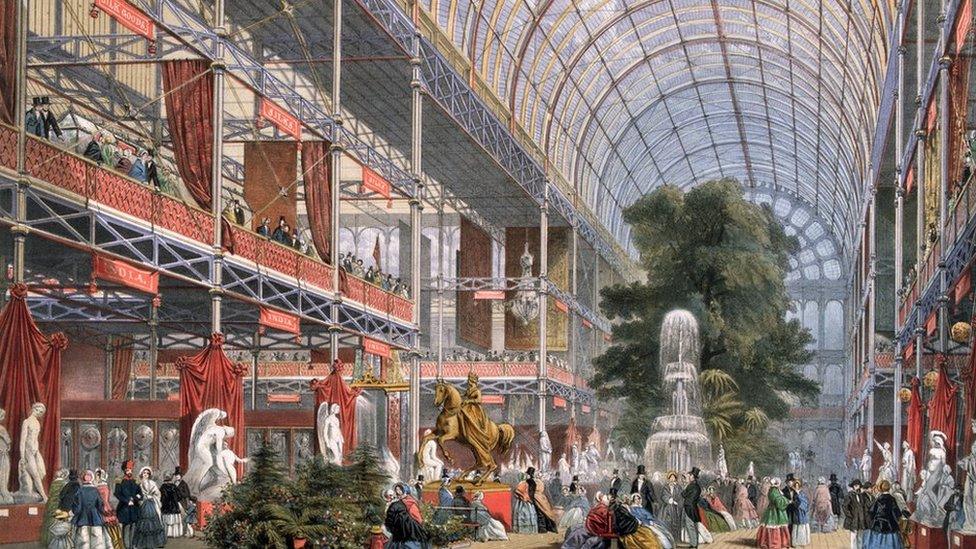

Chance Glass produced 300,000 panes to glaze the Crystal Palace

Chance Brothers Glassworks in Smethwick manufactured glass used in everything from glazing the Houses of Parliament and Crystal Palace to the production of novelty ashtrays.

"If it was made in glass then Chance Brothers made it," said Ray Drury, the firm's final chief engineer, on its 150th anniversary.

When the company was founded in 1824, the world was changing rapidly. The booming shipping industry meant wrecks became a regular occurrence as more ships had to navigate treacherous coastlines, according to historian Malcolm Dick.

In response to this, Chance Brothers created optic lenses for lighthouses that were sent around the world, illuminating coasts and saving thousands of lives.

But since shutting its doors in 1981, the number of their lighthouses has dwindled and with it, the traditional skills needed to produce their hallmark glass.

Workers at the glass firm made prisms for the lighthouses

The Chance Brothers factory in Smethwick closed its doors in 1981

Mr Nguyen has no attachment to the original company, which employed 3,500 people at its height.

But his team, which adopted the name Chance Brothers Lighthouse Engineers, has dedicated itself to restoring and repairing lighthouses using traditional methods and original parts and has done so at more than 100 sites.

Travelling the world, they gather broken parts and repair them and now have enough to be able to fix any lighthouse without replacing anything with modern technology.

Tim Nguyen says his team are the only people taking on the preservation work of lighthouses

Although he repairs lighthouses around the world, including this one in the US, Mr Nguyen said the work made him feel closer to the West Midlands

Mr Nguyen said: "We travel the world to assist in restoration and salvage parts.

"Basically, we're like a car-wrecker. That's how we work until one day when we team up with a glassblower who can make crown glass - then we can make anything."

Crown glass is the original type of glass used in Chance Brothers' optics.

But new production methods mean that the colour and composition of modern glass would not match the original glass if it was added now.

Lighthouses made in the Midlands saved thousands from shipwrecks as the shipping industry boomed

Mr Nguyen has so far not been able to find anyone with the glassblowing skills in Australia to replicate the Chance Brothers' methods.

"We've looked everywhere and can't find anyone that can cast crown glass," he said.

"I believe some people in England can probably do it. If we have a chance of finding someone who can do it, it'll be there."

This lighthouse in south Wales also has an original foghorn made in Smethwick

Mr Nguyen said with a crown glassblower on the team, they would be able to recreate the Chance Brothers' original workshop and even return it to Smethwick.

"One day, when we have this operational workshop we would like to move it back to the Black Country," he said.

"We're trying to do this project on our own, which isn't easy - but I believe it will be done in my lifetime.

"The community over there, their jaws would drop if we brought it back."

There are about 2,300 lighthouses around the world with lenses that were made in the Black Country

Regional heritage projects and plans to redevelop the factory site go some way to ensuring the past is not forgotten, but Mr Nguyen wants to go further.

"Archives preserve the documents, the restoration will preserve the buildings, but nobody is trying to preserve the techniques," he said.

"We are here to preserve and carry on the engineering side, because if we don't it'll be lost. After doing this work for 20 years, that knowledge is too valuable to be lost.

"Basically, we're the only ones doing this work."

But is Mr Nguyen vainly fighting the tide of modernisation?

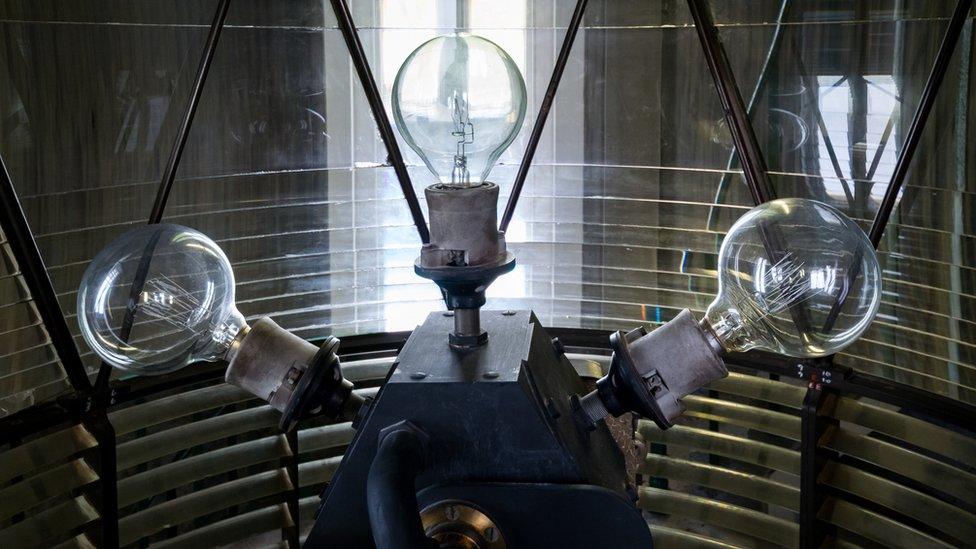

Nash Point lighthouse switched to a more modern bulb in 1998

Like many others, Nash Point lighthouse, near Marcross in south Wales, made the change to a new automated lens several years ago.

Attendant Chris Williams said the new 150 watt lens has a "much smaller bulb" but is "more reliable and stays brighter for longer".

The original Chance Glass optic, which typically contained a 1,500 watt bulb, was left on display but out of use.

The original optics at Nash Point are no longer in use, but remain on display

"Generally speaking, traditional optics are being phased out because new technology is so much more efficient," according to David Taylor from the Association of Lighthouse Keepers.

"Restoring a glass optic is hugely expensive. Within 15-20 years there probably won't be any left."

Regardless, Mr Nguyen persists, so keen is he to preserve this slice of history. But he's not the only one with an interest in keeping the tradition alive.

The small team based in Melbourne travel the world preserving lighthouse optics

Mark Davies founded Chance Glass Works Heritage Trust after stumbling across a Chance Brothers lighthouse, purely by happenstance, in Australia.

The group plans to regenerate the original factory site in Smethwick and build a 30m tall lighthouse to teach people about the area's industrial legacy, which Mr Davies says is "our best-kept secret".

"The story started at the top of a lighthouse in Australia. I saw the manufacturer's plate and it said 'Made in Smethwick' and it stunned me.

"I was born four miles away and I didn't know about it myself. Outside Sandwell, there aren't many people that know about Chance Brothers."

The Black Country's history of light, it seems, needs a spotlight itself.