Red Robbo: The man behind 523 car factory strikes

- Published

Derek Robinson, nicknamed Red Robbo, died on 31 October 2017

He was a controversial figure throughout his lifetime but Derek Robinson remains a working class hero to many. Vilified by the media as "Red Robbo" he was also betrayed, in the eyes of his supporters, by trade union bosses. Following his death on Tuesday aged 90, BBC News examines his legacy.

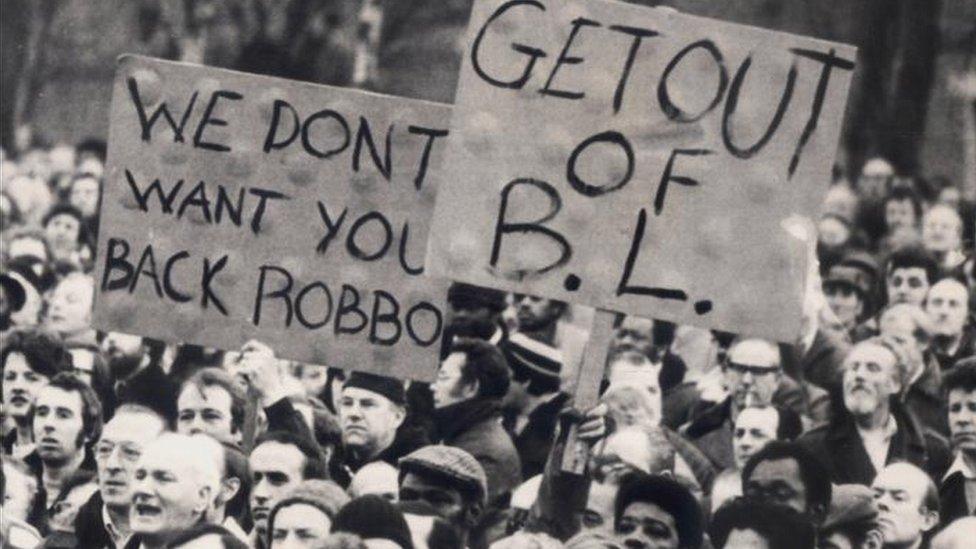

In February 1980, less than a year after Margaret Thatcher became prime minister, thousands of car workers gathered following the sacking of one man.

Union convenor Derek Robinson had been dismissed months earlier by British Leyland's chairman Michael Edwardes. Management regarded him as an "insidious influence" and his days at the car firm had been numbered.

A communist, he had led 523 walkouts at the Birmingham car plant during a 30-month period, gaining the nickname Red Robbo from journalists and becoming an increasingly divisive national figure.

Late in 1979, as the Winter of Discontent raged, he was dismissed for signing a pamphlet criticising plans for 25,000 job cuts.

But instead of supporting him, the workers who gathered that February day turned on him. A motion for a strike in favour of his reinstatement was overwhelmingly defeated - 14,000 votes against to just 600 in favour.

A motion for strike action protesting against Mr Robinson's dismissal in 1980 was overwhelmingly voted down

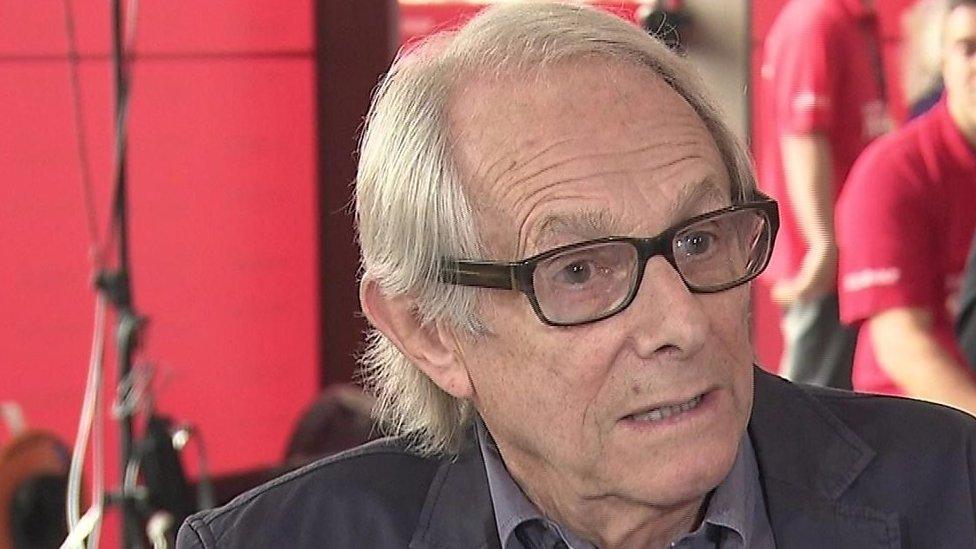

Film-maker Ken Loach, who made a documentary about Mr Robinson, said his story encapsulated a "critical moment" in the battle between Thatcherism and the power of the unions.

The director believes Mr Robinson was "betrayed" by a union leadership with whom he had a thorny relationship.

Initially, the workers came out in support of Mr Robinson, he said.

"There were big strikes across British Leyland, but union leaders instructed them to go back to work," Mr Loach believes.

They had "consciously got rid of him".

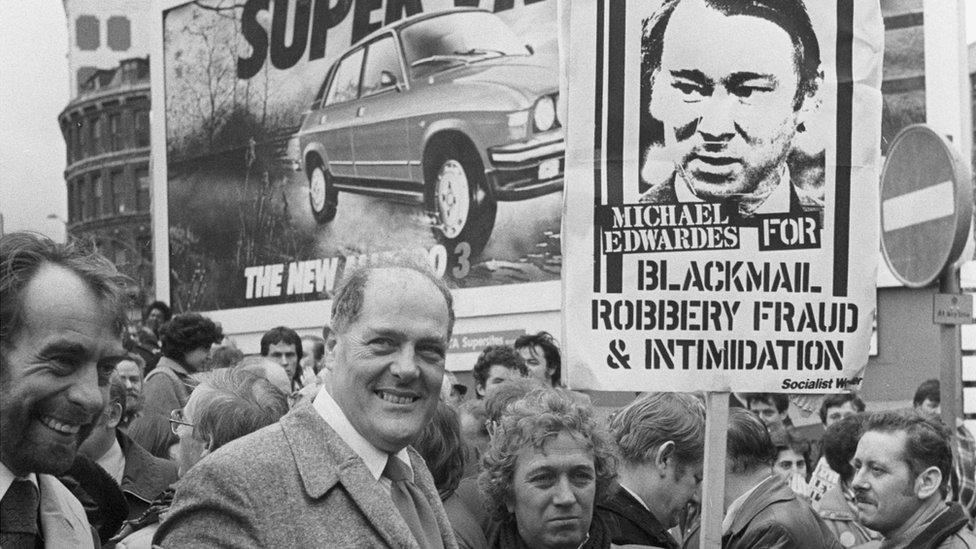

British Leyland, Mr Edwardes wrote, was perceived as being a business "at war with itself"

Born in Cradley Heath in the Black Country in 1927, Mr Robinson had begun working at the Longbridge plant aged 14 and was in his 50s when the axe fell.

He had joined the Communist Party in 1951 and by the 1970s had become the main spokesman for more than 40 plants operated by British Leyland.

But the car giant had been hit hard by post-war economic struggles and had developed a reputation for producing low-quality cars.

By 1975, it had been bailed out by the government, which now owned 95% of it. Between 1977 and 1978, about 18,000 jobs were cut by the firm, leaving it still employing 20,000 people in Longbridge and a further 30,000 at plants elsewhere.

Mr Robinson led the fight back, organising hundreds of disputes. These were blamed by managers for delays to production of 62,000 cars and 113,000 engines, costing the business an estimated £200m.

But the political mood of the country was changing. By the winter of 1979, as 1.5 million public sector workers were on strike across the UK, the Labour government was in its final throes. Mr Robinson was among those trade unionists soon to lose their grip on power.

Film-maker Ken Loach described Derek Robinson as a man of "iron principle"

Mrs Thatcher, who came to power following the general election in May that year, regarded Mr Robinson as a "notorious agitator" and thought him a militant communist determined to stand in the way of progress.

British Leyland's chairman Michael Edwardes shared that view.

He wrote in his 1983 book, Back from the Brink, that Mr Robinson had "kept Longbridge in ferment and upheaval" for years and "disruption and upheaval" were his "food and drink".

He was sitting opposite Mr Robinson when the union convenor was finally dismissed.

But why had Mr Robinson's fellow workers not supported him?

For many, Mr Robinson is remembered "very badly", according to Chris Cowin, an expert on British Leyland's history.

"He's seen as a troublemaker, someone who resisted attempts to modernise," he said.

Strikes co-ordinated by Mr Robinson cost British Leyland £200m in lost production, according to chairman Michael Edwardes

Former Leyland worker Stephen Cox said Mr Robinson was regarded by many as "way out on an extreme". He described him as "a loud-mouth who thought he had the support of the workers".

"He may well have had absolute belief in what he was doing, but few others did," Mr Cox added.

Not all former workers agree.

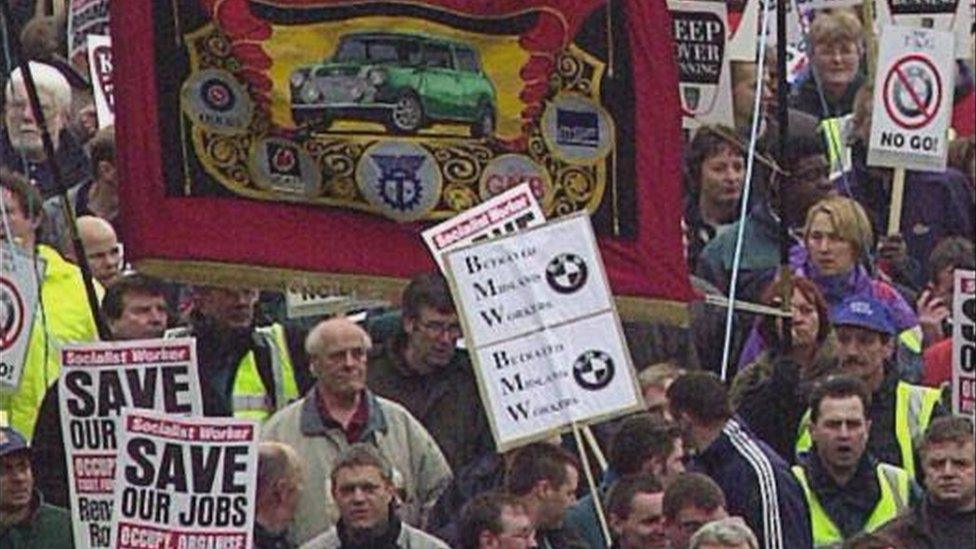

Christopher Lunt worked at Longbridge until MG Rover - the successor company to British Leyland - went into administration in 2005.

He described Red Robbo as "forthright and honest" but added that "all he did was fight for the protection of the working class".

The Winter of Discontent saw rubbish piled high, as seen here in London's Leicester Square

Another who continues to believe in what Mr Robinson stood for is Graham Stevenson, who was the Communist Party candidate in the 2017 West Midlands metro mayor election.

He hopes his friend will be remembered as "one of those stalwarts in the post-war era that maintained a better life for ordinary people", not as an "agitator" or "destroyer" which he said was "a complete invention".

For Mr Stevenson, the dismissal of Red Robbo was "the first shot in the war that Thatcher began against working people and their families".

"He wasn't at all like what the media portrayed him as in the 1970s," he said.

"He was a very competent man… in private life he was very kind and very caring."

Following his dismissal, Mr Robinson worked as a tutor in trade union studies during the 1980s and 1990s, teaching shop stewards.

"His legacy ought to be that you've got to fight," said Mr Loach. "He's to be hugely respected."

As for his Red Robbo nickname, Mr Robinson told MPs in 2000 he regarded it as a badge of honour.

"I can sleep sound at night because I never betrayed the workers I was elected to represent," he said.

In 2000, Mr Robinson was among crowds in Birmingham campaigning to save jobs at MG Rover

- Published31 October 2017