Healthcare for the homeless: 'I probably wouldn't be alive without them'

- Published

Who looks after the health of the homeless?

Homeless people face various challenges: where to find the next meal; where to seek shelter on a cold night; how to protect themselves from the threat of violence. A specialist service in Birmingham is trying to make life easier for them in one specific area - where to turn when they need medical help.

Kaece McGowan was living in a hostel when she first visited the Homeless Health Exchange - an NHS practice exclusively for people who are homeless.

The then 20-year-old, who had been living abroad, returned home because of visa issues and found living in Birmingham "a bit of a struggle". Without the surgery, she said, she might have died.

"I had no support network, no friends, no family around - I felt a bit trapped and overwhelmed," she said.

"I got into quite a bit of trouble when I first came here."

She found herself mixing with "bad people who knew how to have a good time", was taking drugs, drinking, got fired from jobs "a lot", was the victim of a sexual assault and was herself arrested for assault.

She was struggling with her mental health, which she says has been a "difficult" thing for her in the past.

Eventually, she was taken to the surgery by one of the hostel's support workers.

"I can be very difficult, I can lose my temper, I can get very emotional and have weird outbursts - and here they are, really calm, really understanding; they understand that when I am 'on one' I am not like a normal patient," she said.

"I go a bit over the top and become a bit outlandish, so their patience is really good."

Kaece began working with psychotherapist Karen Loly.

"We see some very complicated people with very troubled histories," she said.

"We give them more time than they might get elsewhere."

Dr Sarah Marwick has worked with the homeless for 16 years

The Homeless Health Exchange, located just outside the city centre, has just over 1,000 patients on its register, more than double the number it had when it opened 16 years ago.

Typically, patients are aged in their 30s or 40s, although they present themselves with symptoms comparable to people in their 70s - something surgery GP Sarah Marwick describes as "shocking".

The average age of death for a homeless man is 47. For women, it is 43.

It is estimated 18 of Birmingham's then population of 12,000 homeless people died in 2017 - the number of deaths totalled about 600 across England and Wales.

The health exchange, which gets £628,000 funding from the Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Trust, sees a wide range of people. Many have issues caused by drug-taking and rough living, but patients also have issues similar to people seen in mainstream GP practices.

The difference tends to be that they only turn up at the surgery when a danger point has been reached.

Kane Walker died near the Bullring shopping centre in Birmingham in January

Over the years, Dr Marwick has seen young people with acute liver disease, sepsis caused by drug use, patients with infections so bad they have needed double amputations, and those who are psychotic.

She remembers one 28-year-old man whose spine became so infected it essentially crumbled, leaving him paraplegic. He died shortly afterwards.

She can cite the cases of three people who have had amputations and still live on the streets.

"I have had occasions where I say to someone you need to go to hospital or you will not be alive tomorrow," she said.

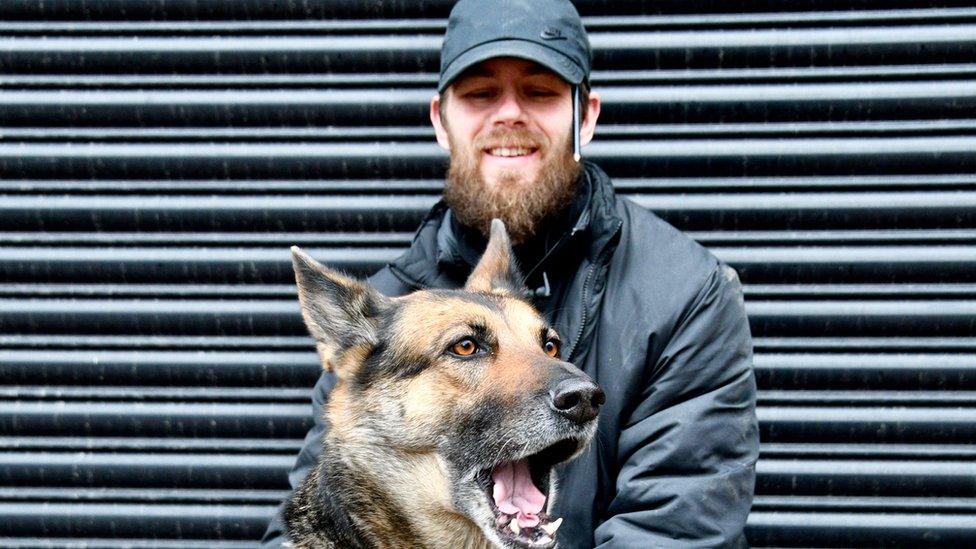

"But other priorities such as getting their heroin or looking after their dog will take precedence."

One patient, a 27-year-old man who did not want to be indentified, has arrived at the surgery for a prescription to help his depression. He has been seeing the GP, he says, since his relationship broke up.

"I don't know what I would do [without the surgery]," he said.

"Without it some people would die out there. There's nothing else for people. I've lived elsewhere and there was nothing like that there.

"People have no-one to talk to. They would go mad or kill themselves. Or end up dead because of the cold."

Rough sleeper Sebastian Nowak, 42, spent the previous night in a car park. He is seeing a nurse as his healthcare certificate was rejected - and he could face a penalty charge of up to £100

It used to be the case the vast majority of people Dr Marwick saw would be older men with alcohol problems. Then it became men in their 30s or 40s addicted to heroin or diazepam.

Now, overwhelmingly she says, it is even younger people addicted to spice or mamba - a synthetic drug that can leave users in a zombie-like state.

Resuscitations at the surgery are common.

"I have never known anything like it," she said recalling a recent incident with a patient who ran naked through a corridor, somehow convinced he was dead.

"It is getting worse. It's all about that now - not heroin so much. It's had a massive impact on health."

Recent law changes, which saw a blanket ban on so-called legal highs brought into force across the UK, haven't prevented drugs like spice being sold, but the substances are now even more unregulated and stronger, and easier to get hold of, Dr Marwick said. And, there is no reversal agent, so doctors find it difficult to treat those who have taken these drugs.

The practice is close to Birmingham's city centre, behind the Snow Hill district

Despite its best efforts, many homeless people do not want to engage with the health exchange and its staff.

A mistrust of the system from people who find it hard to trust the authorities is one reason given, another is that their own health is not a priority.

It is an issue exchange staff are all too keenly aware of. To try to combat this, nurses do outreach work, walking through the city centre to visit the places where rough sleepers are known to congregate.

Substance misuse nurse April Stoneman and community psychiatric nurse Joanne Westwood spend about 90 minutes walking through the city on a typical session.

Jessica, 38, was homeless for more than a year but has recently managed to find accommodation. She is seen regularly by outreach nurses who stop to chat and check on her health

They approach people they see sitting in the streets and ask if there is any help they need.

Some people chat to them like old friends, some wave them away. Some agree to meet later at the clinic but often do not turn up.

The rejections do not matter, the nurses say. The only way to get homeless people proper treatment is to keep approaching them to remind them the service is there.

"There would be a lot more people dying if we weren't here," Ms Stoneman said.

Community nurse Clare Cassidy also runs outreach sessions.

She has been with the service for 15 years and in that time has treated people who have been set on fire, and known patients who have later been murdered and then been called upon to identify their bodies.

Clare Cassidy, pictured here treating a patient at a drop-in centre, says the threat of violence is greater than it used to be for homeless people

"I thought I knew Birmingham when I started this job but there has been a whole layer of humanity I knew nothing about," she said.

"I think it is getting a lot more violent for [the patients] - there is a lot of aggression on the streets both between themselves and from the general public. It's hard to believe sometimes," she said.

Part of her job is to run the drop-in clinics, which are held daily at the health exchange and weekly at Sifa Fireside, a charity-run drop-in centre.

Her patients have varying needs. A typical clinic can include dressing wounds, assessing and treating leg ulcers - common among drug users - treating eye problems and looking out for people with diabetes, asthma or blood-borne viruses such as HIV, which staff say they are now seeing more of.

Ms Cassidy can see someone who has been beaten up and threatened or someone who just wants to chat. She also helps patients access a free prescription service, which some can find a rather complicated process to navigate.

"You are never sure which hat you are wearing in this job," she said.

Nurses April Stoneman and Joanne Westwood are keen to let people know where the surgery is and what it offers, despite often coming up against rejection

"These people don't fit into a normal GP setting - they would not manage to get an appointment," Dr Marwick said.

"You have to understand the group. I really like the job - it is incredibly challenging and it is difficult and I have seen some of the sickest people, but if you take the time to talk to them and show interest in them, then it is beneficial and rewarding.

"You might be the first person to have shown an interest in them."

Most GP surgeries have a zero-tolerance attitude to patients who behave badly.

The Health Exchange is more tolerant. Staff are sworn at and shouted at on a regular basis. Violence, however, is rare.

Ninety per cent of patients are men, most of whom have become homeless after losing a job or a relationship breaking down.

"Women tend to be better at looking after themselves; they generally have better social support and, if they have children, they don't tend to stay homeless too long," Dr Marwick said.

David Onassis, 58, getting a check-up at the Sifa drop-in centre, where he was also helped with finding accommodation. He'd like to work there as a volunteer, he says

Going forward, she would like to see a shift in how healthcare for the homeless is provided.

Nationally, she said, the country works on a recovery approach rather than a harm reduction one - for example, someone might be put on methadone to treat an addiction rather than have the addiction spotted before it got out of control.

The recovery approach to medicine suits some people, she said, but not those whose lives are so chaotic they cannot manage to look after themselves. They end up not getting a service at all.

"My mission in life is to get equality of access for the homeless for health services and everything else. As a city, we should be embarrassed if we can't do it."

As for Kaece, she credits the practice with helping her getting her life back on track to the point that now, several years later, she is in her first year of university studying psychotherapy and counselling.

"If I hadn't had the guidance and support from the staff here, I would have made some very bad life choices and I probably still wouldn't be around today."

Photography by John Bray

- Published25 February 2019

- Published4 February 2019

- Published2 January 2019

- Published29 December 2018

- Published20 December 2018

- Published22 November 2018

- Published7 November 2018