Will Birmingham's boom benefit all?

- Published

Cranes dominate the skyline in Birmingham as construction booms

Birmingham city centre is undergoing its biggest transformation since the 1960s, as businesses relocate from London bringing with them jobs and investment. But will the boom help the inner city areas or a rising homeless population?

There's a new soundtrack to life in Birmingham and it's hard to avoid. It is a cacophony of drilling, banging and crashing, caused by workmen, lorries, diggers and cranes lifting steel girders and mixing cement.

Not since the city was redesigned in the 1950s and 60s has it seen so much change.

As London becomes even more expensive, businesses are relocating to the UK's regional cities and thousands of workers are moving with them.

According to the annual Deloitte Crane Survey, external, which measures new projects in the city centre, residential development in Birmingham is at an "all-time high".

It says 16 new schemes have been completed in the past year and - at the same time - more than 20 have begun construction including offices, apartments and hotels.

Edwin Bray, a partner at Deloitte real estate in Birmingham, said: "It's a major transformation of the city centre. A lot of people who come here and haven't visited for a while talk about it being a building site.

"But if you can imagine it in two or three years' time, it will be completely transformed."

The biggest and most visible development in the city centre is called Paradise Birmingham.

Residential development in Birmingham is at an all-time high

It has caused so much disruption to roads, public transport and walkways that it is easy to get lost, even if you are not a first-time visitor.

The old Brutalist central library and the Paradise Forum shopping precinct have been demolished to make way for two huge new office blocks, one of which has already been let to professional services firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC).

In Centenary Square, HSBC has begun moving in to its new HQ and behind it construction continues apace on new offices for HM Revenue & Customs.

Along with Deutsche Bank and KPMG, which already have large bases in Birmingham, the financial and services sector has helped drive inward migration from the capital where the cost of living is prohibitive.

Thousands of so-called millennials, aged 25 to 34, have relocated.

Liesal Ackerman, who is expecting her first child in the next few months, moved to Birmingham with her husband from London.

Over a coffee she told me why.

"Since we've moved to Birmingham we've bought a three-bed semi in a nice area, five miles from the city centre."

Liesal Ackerman says Birmingham has transformed since she was at university in the city

Before she moved she commuted to London from Southampton daily because they couldn't afford a property in the capital.

She hadn't visited Birmingham since she was at university a decade ago and says she was delighted by the transformation.

"It feels 100% different from what it was 10 years ago. There are brilliant restaurants and bars that would rival anything in London.

"But equally I think I had a prejudice about the regions generally. Before, I felt that the only place I could have my career and lifestyle was in London."

The 2022 Commonwealth Games and HS2 are driving the development but the city council can claim credit too.

The authority says it's made cuts of £650m since 2010 and halved its workforce, but it has also worked to make property available and encourage the developers.

Not just at Paradise, but also at another major development - called Smithfield - which is under way across the city near where the new HS2 rail terminal is also being built.

Brigid Jones, the council's deputy leader, says even though there are concerns it could affect other services, spending money on big projects will benefit the city and the wider West Midlands.

"We went bidding for the Commonwealth Games because it is going to put Birmingham on every TV screen in the world and showcase the city for what it really is and bust the outdated stereotypes.

"For every pound we put in we get £3 from the government, and we're looking at a half a billion pounds boost to the economy."

You might also like:

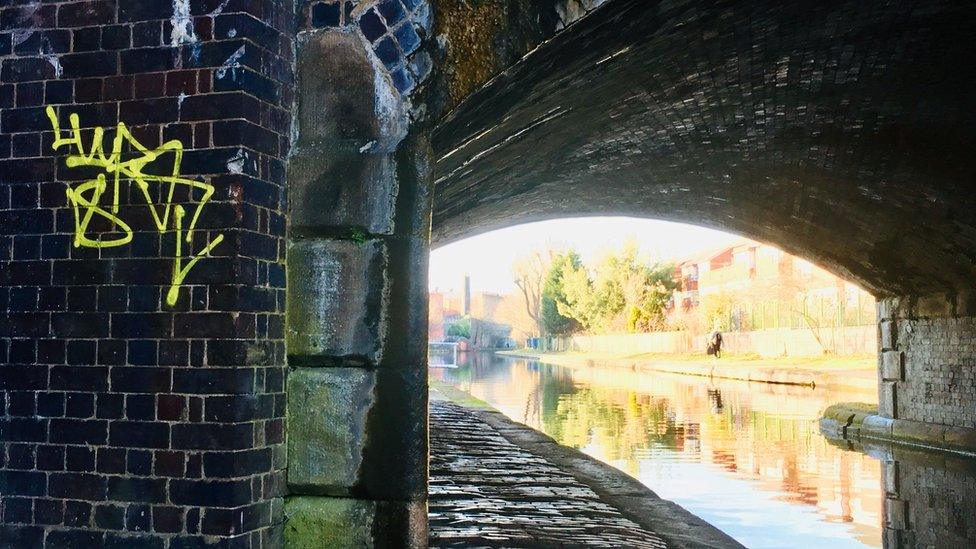

However, a short walk from the bustling centre, along the canal past the ICC and Birmingham Arena, the sound of construction disappears.

The ultra-modern glass and steel buildings make way for empty factories and old council houses in the Ladywood district.

Ladywood is right next to the city centre

Nora Higgins, who has lived here for 20 years, says she fears the boom in the city centre isn't being experienced by everyone.

"We feel like we are suffocating and we're going to be pushed out as a community," she says.

"I think they're concentrating too much on the city centre. They're not doing enough for us."

The most tangible benefit for people living in Ladywood is that the Metro tram line will be extended to make it easier to connect with other public transport.

There should be more effort put into the suburbs, says Nora Higgins

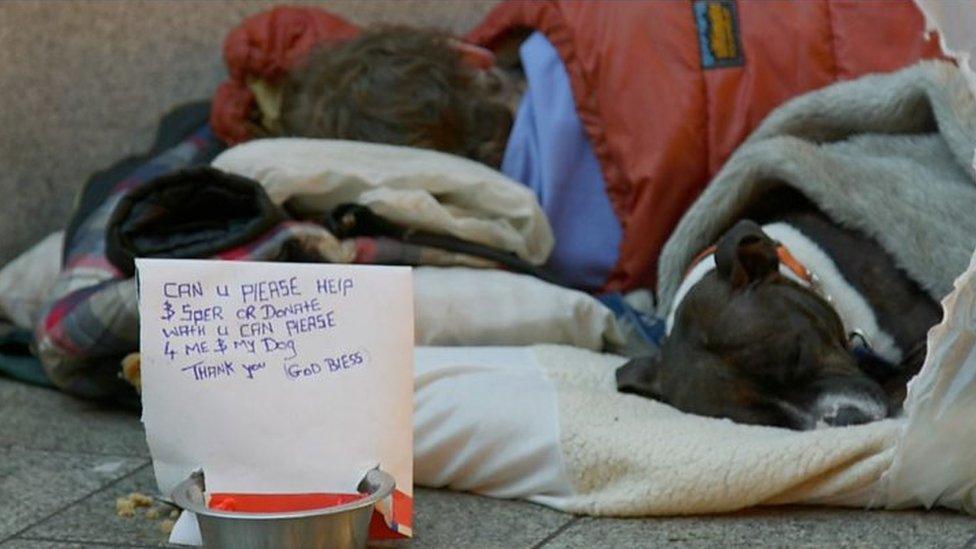

There is another painfully visible problem affecting the city too. If you lower your gaze to street level from the impressive construction work overhead, you will see homeless people begging.

The latest rough sleeper figures showed there were 91 people on the streets of Birmingham, compared to just nine in 2010.

The death of one rough sleeper, Kane Walker, in January inspired a protest march led by student Chelsea Reynolds.

"I've lived here all my life and I think the homelessness crisis in Birmingham has got visibly worse in the last couple of years," she says.

"I wanted to do something about it, to show homeless people that we care about them, we value their lives and we are not accepting this any more."

In attempt to improve the situation Birmingham has secured nearly £10m of government funding to pay for a new scheme called Housing First.

It's based on a project of the same name which has been very successful in Finland.

The money is spent on providing more permanent accommodation for rough sleepers as well as a support programme to try to tackle the issues that forced them on to the streets.

There are also several outreach teams provided by different charities and agencies, and a growing band of volunteers providing medical support and sustenance to the city's rough sleepers.

Chelsea Reynolds organised a protest over the death of rough sleeper Kane Walker

Conscious of the disparity in wealth between the city centre and its neighbouring areas, the council also asks developers for guarantees they will recruit locally.

Although these are non-binding agreements, several have made a point of recruiting staff from inner city areas like Ladywood.

Matthew Hammond, senior partner at PWC Birmingham, said it was an important part of the company's ethos.

"My measure of the success here in 10 years or maybe 20 years' time is are there children coming out of schools in Ladywood that understand what goes on in these glass, steel and concrete towers and do they work there?".

Matthew Hammond hopes to employ staff from inner city areas at PWC

I wrote four years ago that after decades of stagnation Birmingham looked set to turn a corner .

The pace of transformation is surprising even to someone who has worked here for more than a decade and a half.

But the contrasts are still stark, and businesses and government say they are prioritising ways to address the issue.

The city is set to change again in the next five to 10 years, almost beyond recognition. It has become more prominent as a global destination and is benefitting from massive investment, especially from China.

The city still lacks one thing which would help boost its global brand - it doesn't have a powerful Premier League football team, although Wolves are doing their best for the wider West Midlands.

There's the new Smithfield development, HS2, the Commonwealth Games, a Clean Air Zone, and this is where 5G will be launched.

Channel 4 may not be coming to Birmingham but BBC Three already has.

In a few years the first stop for visitors after they arrive at Grand Central could be Paradise.

- Published3 September 2018

- Published12 April 2018

- Published13 February 2018

- Published31 January 2018