Birmingham knife crime: 'In a few hours you could be dead'

- Published

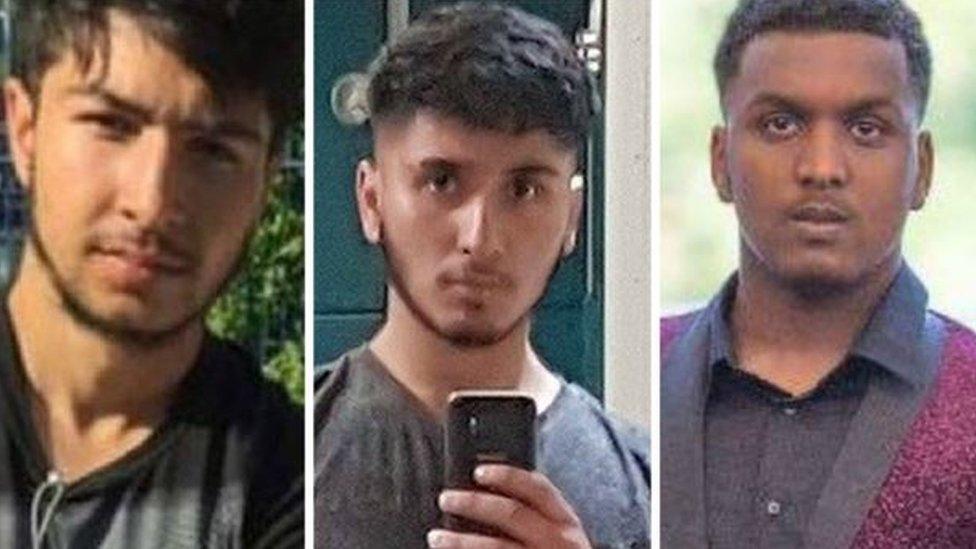

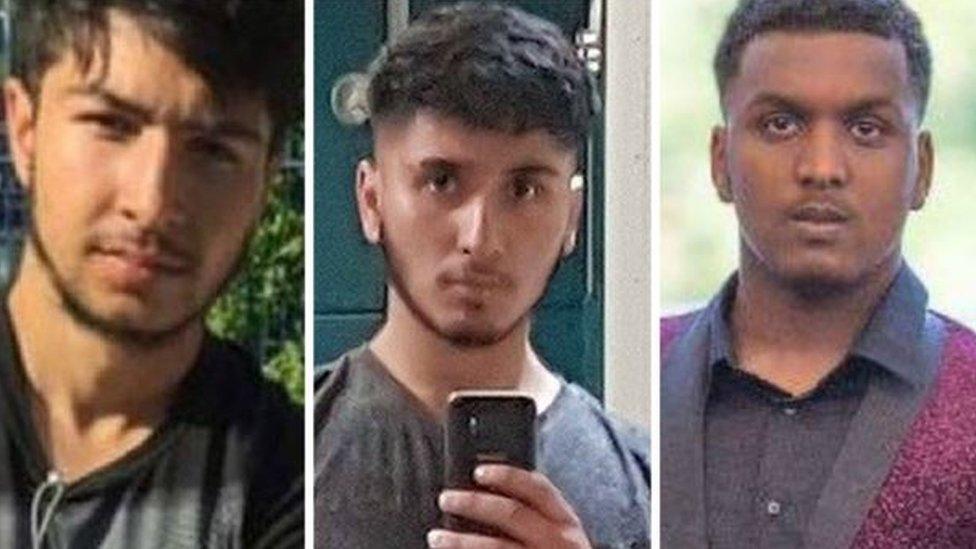

The three teenagers stabbed to death in 12 days: (l-r) Hazrat Umar, 18, Abdullah Muhammad and Sidali Mohamed, both 16

Three teenage boys have been stabbed to death in Birmingham within days of each other. As the city battles a rise in knife crime, many questions remain. What has led to the deaths of these boys - and what is being done about it?

Birmingham is used to seeing violent crime but this recent spate of stabbings has shocked many.

The killings happened within a three-mile radius in suburbs of east Birmingham largely populated by those from minority backgrounds.

Two of the boys were 16, one 18. Two of the stabbings happened in daylight - one was at a college as students left for the day, another in a residential street at 14:00 GMT.

The third was in a park at 20:00.

Why is this happening?

Some of those who work with young people in Birmingham say social media has an often fatal role to play in the violence.

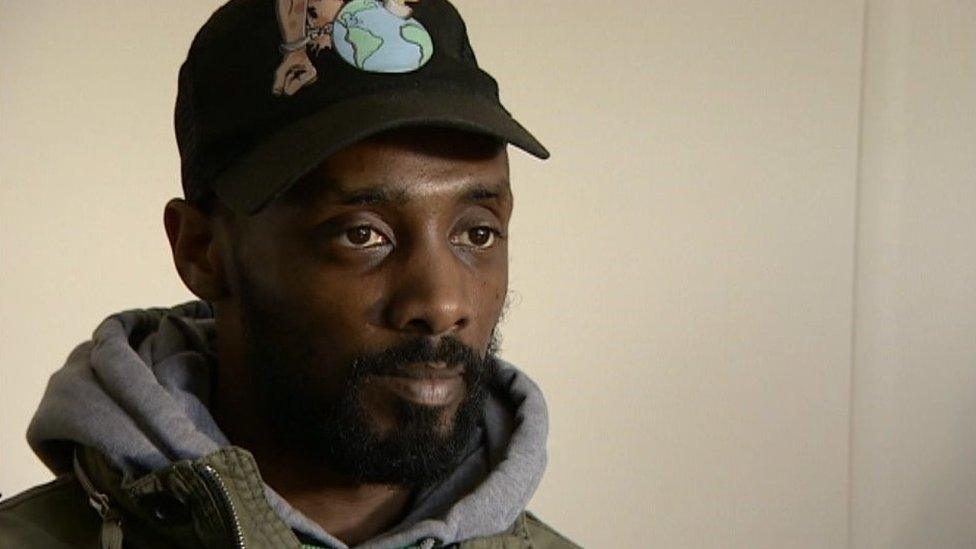

Simeon Moore, a former member of infamous Aston gang the Johnson Crew, now works with young people to help them turn away from carrying a knife.

Simeon Moore said social media meant disagreements could escalate very quickly

He said: "It used to be that there's a group in one area that doesn't like a group in another, or that a person is being bullied because they're from a particular area.

"That's still the same now, but before, things could take a few days or even weeks to happen, now social media helps it [knife crime] spread, it facilitates it.

"It's instant. And, in a few hours, you could be dead."

The ways young people communicate with each other leads to an "escalation" of violence, Mr Moore said.

"It's not really about the social media itself, it's about what it does to escalate the problem. Disagreements can spread very quickly, instantly.

"You've only got to look at the comments under some music videos online. People kick off in the comments and arguments happen about areas and that's how it starts.

"You can be part of a group that has the disagreement and the next instant you find out someone is dead."

Awez Khan has previously spoken in Parliament about knife crime

Awez Khan, 17, from Aston, who is a member of the UK Youth Parliament for Birmingham and has spoken in Parliament about knife crime, said: "I know people who go to the youth centres and it's kept them off the streets and stopped them having altercations that would turn into violence.

"Young people in these areas, they feel like they have an image and reputation to maintain online and to keep that perfect image they have altercations online and it builds up and up.

"Then when it comes to actually meeting that person, it bubbles up and boils over. That's when it goes from a small online issue to real life violence."

Who were the victims?

Friends and relatives left flowers outside the college where Sidali Mohamed was fatally stabbed

Sixteen-year-old Sidali Mohamed fled Somalia with his family as a toddler, finding refuge in the UK. He lived in the Highgate area, just a stone's throw away from the college he attended.

As a student at Joseph Chamberlain College, he dreamed of becoming an accountant and his father was his best friend.

He was fatally stabbed just yards from the college gates, where his friends and family came to lay flowers after his death.

Abdullah Muhammad, also 16, was in his local park when he was stabbed on a school night. He died at the scene.

The park was cordoned off and a blue police tent marked the spot where Mr Muhammad took his last breath, just yards from a nearby primary school.

The mother of 18-year-old Hazrat Umar visited the scene where her son died in the hours after his death.

Supported by friends and family, she cried behind the police cordon on the residential road in Bordesley Green where he was fatally stabbed.

Mr Umar was an electrical engineering student at South and City College Birmingham. His family and friends said they could not understand why he was targeted.

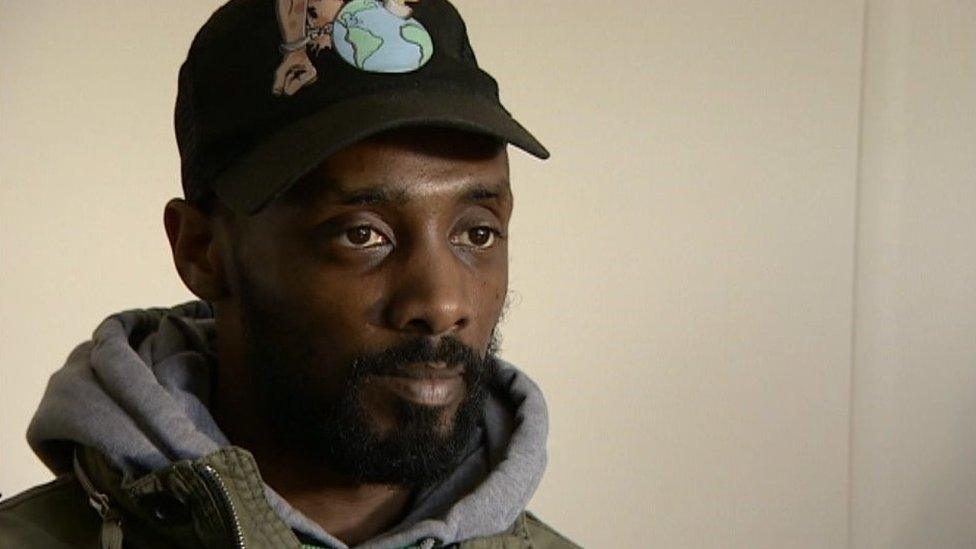

Keelan Wilson was even younger - just 15 - when he was killed in a knife attack just yards from his Wolverhampton home last May, a week before he was due to go on a family holiday.

His mother Kelly Ellitts said: "The more people get away with this, the more these boys think they can get away with it.

"They walk around thinking they're invincible and they can do what they like. It's just going to get worse. Who knows who's next?

"I never though this would happen to me, I thought I was safe. I thought Keelan was safe."

Kelly Ellitts, mother of Keelan Wilson, says boys with knives think they're "invincible"

What challenges do young people face?

Last year, official figures show there was a 45% increase in the number of fatal stabbing victims aged 16 to 24 in England and Wales.

In the West Midlands, there were a total of 19 deaths from knife crime. So far this year, there have been three.

As communities in the city come to terms with what has happened, leaders have spoken of the challenges facing young people.

Nassar Mahmood, a trustee at Birmingham Central Mosque and the manager of Unity FM radio, based in Bordesley Green, said: "People are saying that their children seem to have multiple obstacles that they're facing and are struggling to deal with those.

"This may be to do with their identities as second or third generation immigrants, the pressures to adopt British values, the issues they face in the school system, which is breaking down."

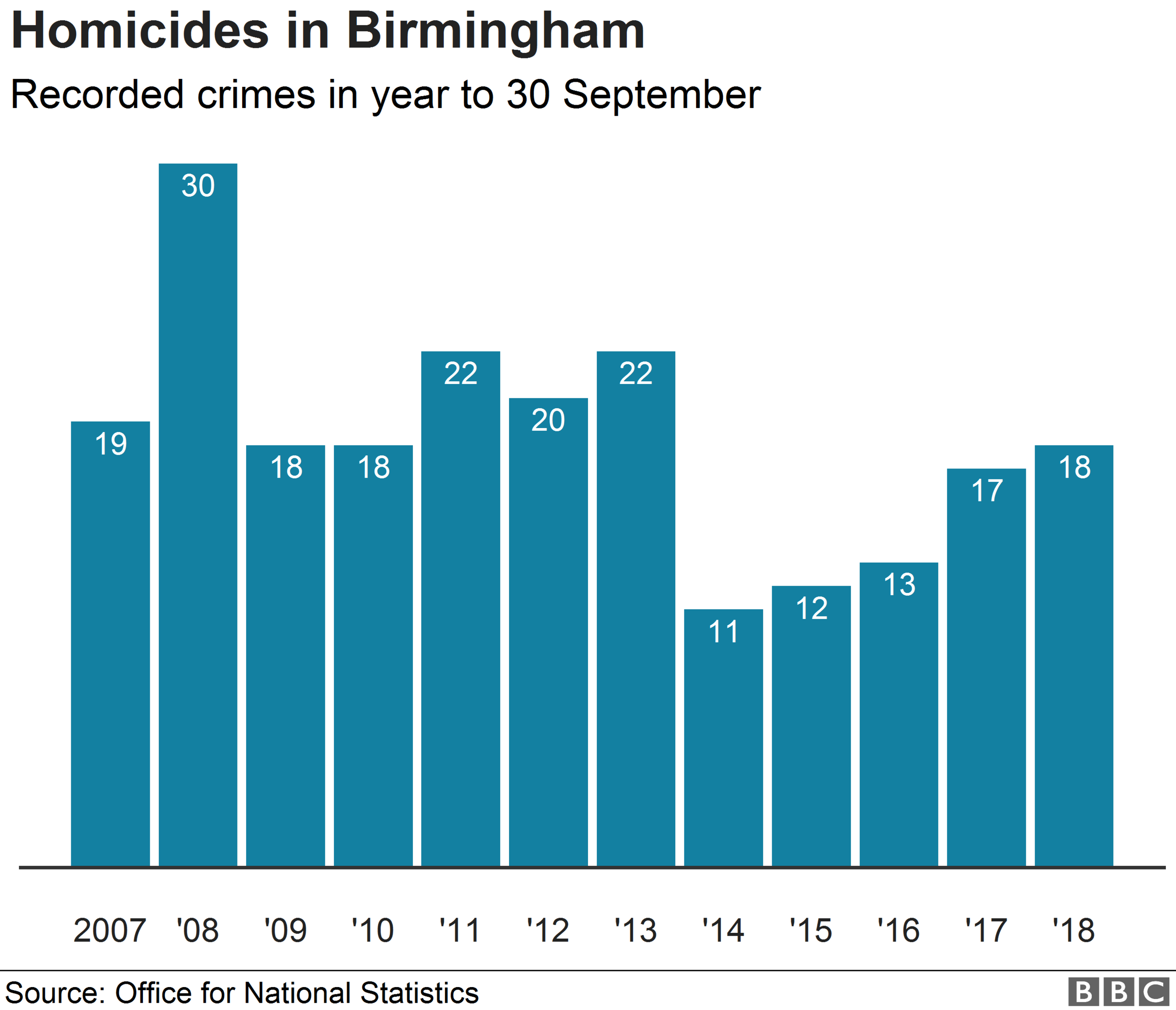

The number of homicides in Birmingham has been rising since 2014 but is still far lower than it was a decade ago.

In the year ending September 2018 there were 18 homicides in the city, up from a low of 11 in the year to September 2014. This does not come as a surprise to Mr Moore.

He said: "A lot of what we are seeing is because the kids are on edge, there's a lot of fear.

"We need to change the mindset and the culture of the community. These young people are already vulnerable to a certain mindset because of poverty, because of their quality of life, the glamorisation of the negative lifestyle.

"They are automatically vulnerable, already susceptible to it and policing on its own won't prevent knife crime from happening.

"The only solution is to invest in the community and help alleviate some of the problems they're facing."

What do the police say?

Dave Thompson said people who made children feel unsafe needed to be targeted

Dave Thompson, chief constable of West Midlands Police, has urged parents to have conversations with their children about where they are and who they are with.

He said: "Arguments and disagreements build on social media or are overheard on the bus and in school or college.

"We need you to play a part in telling someone if a fight or trouble is brewing or if you hear someone has a knife.

"If you spot trouble ask the police or local authority for help. I do not want to arrest young people if we can avoid this.

"We need to target the people who make our children feel unsafe. You have to be part of the solution to this problem."

Where do stabbings happen?

Current police crime figures do not show the number of knife-related homicides in Birmingham.

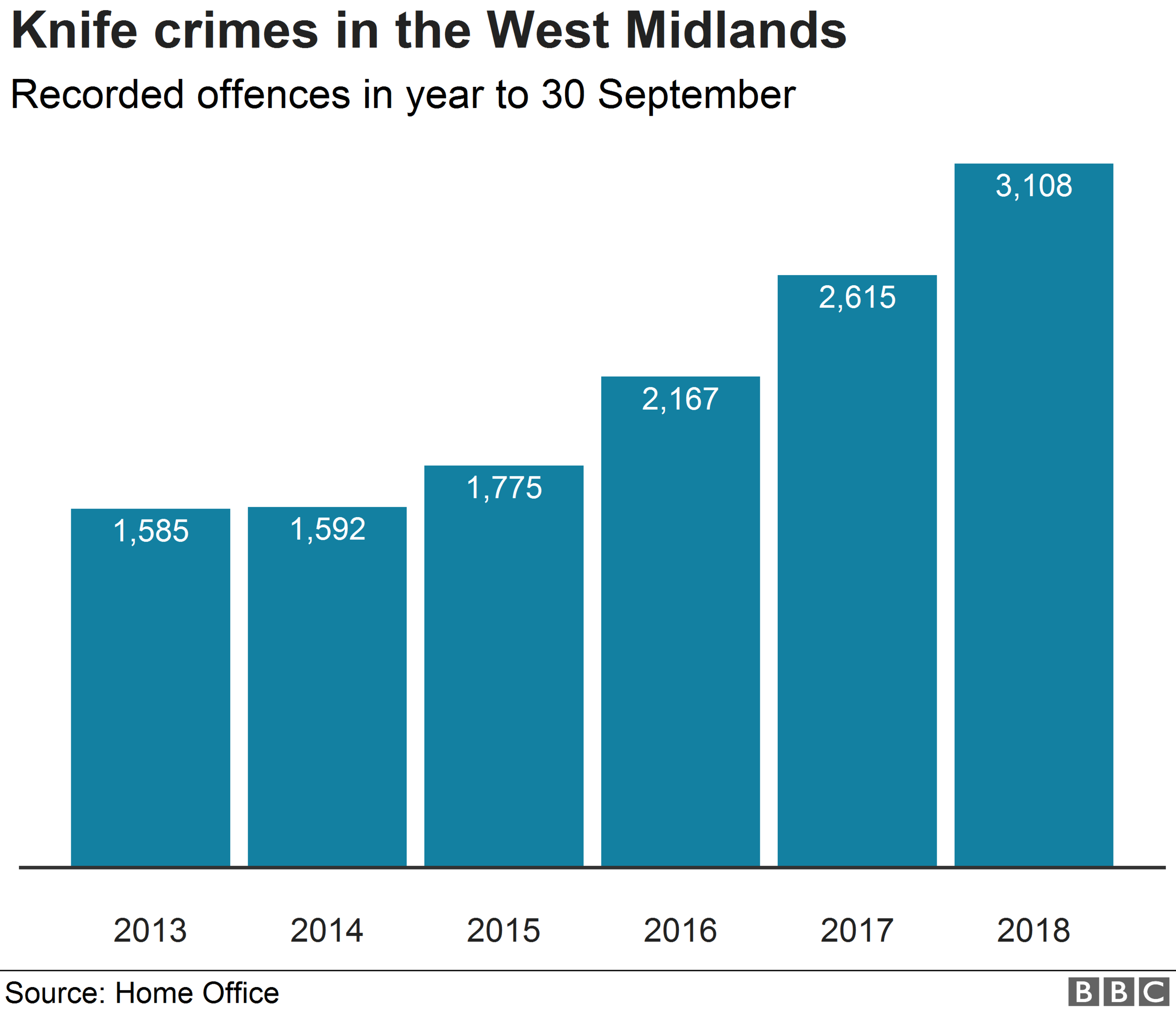

The only available official knife crime data is for the whole West Midlands Police force area, which includes three cities - Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton - and four metropolitan boroughs.

But the specific areas where knife crime takes place are seen as important.

Prof David Wilson, from Birmingham City University, said: "I teach a lot of young people who have been affected by these types of crimes and live in the areas where this type of violence happens.

"I hate labels but these are areas that have long-term problems, particularly of poverty, and have large numbers of young people who are no longer in school and are not formally employed.

"They may be employed informally, sometimes in organised crime.

"Changes in the way that organised crime is run, with the emphasis on finding new markets, making new temporary alliances, sees young people coming and going, with violence changing in a similar way.

"It is reflection of the individualism and immediacy of this type of crime."

Figures published by the police showed in the year up to September there were 3,108 offences recorded, a rise of 19% on the year before and almost double the number recorded in 2013.

Nassar Mahmood said he thinks people are disillusioned by knife crime

Mr Mahmood said the people he had spoken to in the community thought the rise was a reflection of changes in society.

"People were saying they think perhaps the mosque isn't doing enough to help, people are disillusioned, they're frustrated," he said.

"One ex-teacher described it as our society being in tatters as a result of this.

"People don't know what to do."

So what can be done?

A former chief prosecutor for the north-west of England thinks the response from the authorities is not as it should be.

Nazir Afzal, a relative of stabbing victim Mr Umar, said: "The sense of urgency isn't there and my fear is that others will suffer and other deaths will occur until such time we treat it as the emergency it is.

"I think we have become complacent in Birmingham. They tell me these types of attacks and the ones that don't end in deaths happen more frequently and barely register apart from conversations in the streets."

Nazir Afzal was a senior prosecutor but is also a relative of one of the three recent victims

David Jamieson, the Police and Crime Commissioner for the West Midlands, thinks the answer to the knife crime problem rests in providing more opportunities for young people in disadvantaged areas.

"We need the support of local communities to stop this violence. It is not a job the police can do alone and they can't simply arrest their way out of this problem," he said.

The police and communities need to "create more diversionary activities and schemes to divert young people away from violence", Mr Jamieson added.

A community worker in the city, who asked not to be named, said: "This is about resources and what happens when you take things away from certain areas.

"All the centres are closing down, there's nothing for kids in these areas to do.

"The kids that get involved in this have nothing to do, so they get together with their friends on the streets.

"And like all young people they want nice trainers, nice clothes and they want to make a name for themselves.

"That's how they become vulnerable to criminality. Then they think 'I've got to protect my area, I've got to be able to defend myself and my name' and that's how they end up carrying knives.

"Once you carry a knife, that's it."

Data journalism by Daniel Wainwright

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, and sign up for local news updates direct to your phone, external.

- Published27 February 2019

- Published22 February 2019

- Published13 February 2019

- Published7 February 2019

- Published28 December 2018

- Published28 March 2018