Robotic exoskeleton aids hand movement after stroke

- Published

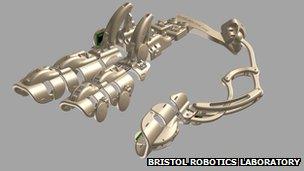

Gerry Lambert tests out a new prototype device from the Bristol Robotics Laboratory following a 'devastating' stroke

Picking up a glass of water would have been almost impossible for Gerry Lambert after she suffered a "devastating" stroke.

She was 52 years old when she lost the feeling in the right side of her body in 1997.

The mother-of-two, from Yate near Bristol, said it left her feeling "helpless" and she relied on friends and family to help her with simple tasks.

She is now helping scientists at the Bristol Robotics Laboratory who have designed a prototype device with the potential to help speed up the recovery of hand movement.

The exoskeleton fits around a person's arm, picks up on the motion of the user's hand and helps provide extra force to complete the movement.

The Stroke Association estimates that 150,000 people have a stroke in the UK every year.

A stroke has a greater disability impact than any other chronic disease, with the most common side effects being physical, such as weakness, numbness and stiffness in the arm or leg or both.

'Felt strange'

Mrs Lambert has been giving feedback to the scientists as they develop the exoskeleton.

"It felt very strange at first because I wanted to control what I was doing with it, but it was the glove that was doing things for me," she said.

"I picked up the glass and then moved it and the glove then automatically released the glass, whereas normally I would have to peel my fingers back from it.

"The concept of it is just fantastic."

Being able to use the hand for grasping and pinching is critical to regaining independence and key to the exoskeleton's design over others, in that it is being developed to be used in the home.

Mrs Lambert has been using one of the early prototypes, but scientists have already developed a new, sleeker version - the details of which are currently a closely guarded secret.

It is lightweight while retaining a large number of motions for everyday activities and keeps the palm of the hand free.

Following the stroke, Mrs Lambert's hand locked in "a claw" when she tried to pick up objects, which would only release if someone physically moved her fingers for her.

The new version of the exoskeleton has been developed to be sleeker and easier to use

"The impact of the stroke was devastating," she said.

"It was like somebody had put a marker pen down the middle of my body, so on my right side, the feeling had gone from my face, my neck, right down my arm and down my leg.

"I just felt so helpless. I had gone from being quite a fit person and being quite independent to suddenly being dependent on other people making me tea and coffee."

Dr Thomas Burton designed the exoskeleton during his PhD with the University of Bristol.

'Triggered by sensors'

It uses a number of new technologies such as 3D printing, that allow the device to be scaled to fit any size hand quickly, with the full exoskeleton able to be built within a couple of days.

It is controlled by a computer, and triggered by sensors on the hand. When the person begins to move, the system detects this and then moves with them.

"It's the idea that you can take a device, then take someone's measurements, and scale that device to fit them absolutely perfectly, and using motors and a battery pack and a small, neat embedded control system, and give someone the extra functionality to complete tasks at home," Dr Burton said.

"This will hopefully increase their confidence... and stops the development of muscle tone, where the muscles on the arm start to function differently because of the non-use of the hand."

'Big difference'

Being able to support someone in their everyday life means that a person's rehabilitation can take place on a daily basis.

Occupational therapist Ailie Turton, from the University of West England, has been supervising the exoskeleton project.

She said: "At the moment we have lots of exercises and activities that we would ask people to do and they will do them a bit, but they don't tend to do them all day long, or often.

"What makes a big difference with this device is that it's developed for use at home. It will be part of their habit and daily life, rather than a chore."

The exoskeleton is still being researched and developed, but Dr Burton said it could be used by anyone needing support to move objects as part of everyday life.

- Published3 October 2011

- Published23 September 2011

- Published18 May 2011

- Published4 December 2010

- Published1 August 2013