Bank of Life: How children of the 90s helped us all

- Published

More than 9,000 placentas float in buckets of formalin stored on the outskirts of Bristol

We know genes affect obesity, that eating oily fish is beneficial during pregnancy and that there is a link between peanut allergies and skin lotions - but where did the evidence come from? Answer - the Bank of Life.

Thanks to the pioneering work of one scientist, who had the foresight and the means to persuade thousands of new mothers to donate tissue samples to the Children of the 90s project, the bank has been supporting national and international medical research since 1991.

As the then new mothers' children continue to donate to the project, the bank in Bristol keeps growing.

It now houses more than 11,000 baby teeth, over 20,000 nail clippings, almost 30,000 plastic bags containing locks of hair. There are thousands of slices of umbilical cords and more than a million tubes of blood cells, plasma, urine and saliva.

All these items are kept in row upon row of freezers except for a stock of 9,000 placentas at another site, preserved in buckets of formalin.

Prof Jean Golding's "collect everything" philosophy was considered unusual 20 years ago

But, talking to CO90s founder Prof Jean Golding, it is clear the study, which tracks 14,541 pregnant women and their babies, might never have got off the ground. She said other professionals told her "people wouldn't do this because they would get nothing in return and they won't see the point".

"But the population saw the point," she said. "Scientists took 15 years to see the point. I did it because I had so many questions that there were no answers to, because nobody had collected the information."

She believed that "what went on before birth was much more important and probably even [more so] before conception, if not the previous generation".

Mothers and babies

14,541

pregnant women enrolled

14,062

babies followed

-

554 of these children are now parents themselves

-

190 daughters of CO90 mums have joined the project

-

44 sons are taking part and...

-

20 couples where both were born to CO90 mums

The mothers who took part

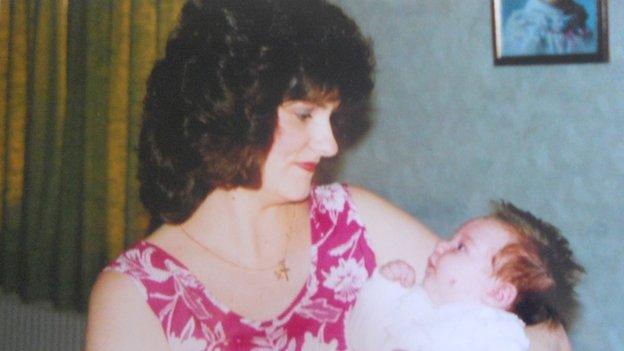

Michele Goulden was the first mother-to-be to join the project in 1991 when she was pregnant with her daughter

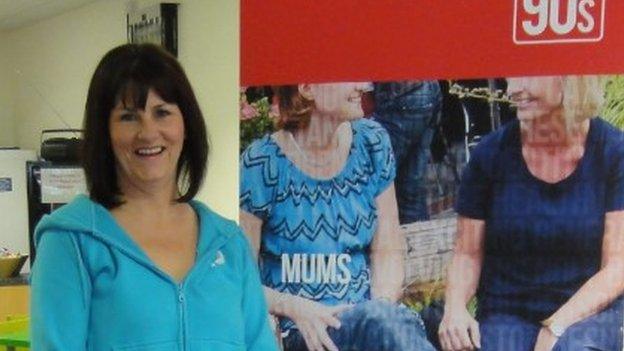

Michele Goulden, now 52, is still taking part in the multi-generational study 24 years later

Michele Goulden was pregnant with daughter Lindsay, now 24, when she was recruited as the first mother by the CO90s.

Ms Goulden said: "When Lindsay was born, I already had a 20-month-old daughter and was obviously keen to make sure that the girls were brought up to be as healthy as possible.

"Now, 24 years later and a grandmother, I still do. Interestingly, Lindsay is now a personal trainer and takes health and fitness even more seriously than I do, often offering me tips on what to eat and reminding me to drink lots of water.

"Possibly, taking part in the study and completing all the questionnaires is partly responsible for her interest so that has been an added bonus."

Some of the original CO90s children have now also become parents and their children are adding to the bank.

Sara Hawkesford was born in 1991 and is now a mother herself and part of the Children of the Children of the 90s

Sara Hawkesford, 23, was one of the original CO90s babies and is now a mother of two boys. She donated her placentas and other samples following her pregnancies. She said the labour of her second son was so quick she almost forgot to hand over the placenta.

"They were about to wheel it away and Alex [Sara's partner] said 'stop' and had to run out to the car and get the special bucket," she said.

"You're doing something for science and are involved in new discoveries. It makes you feel a bit valuable. And it's good for the kids to be involved from an early age so they can look back and say I was a part of it and did help in a small way."

Bank of life

Samples stored

197,168

tubes of urine

29,947

bags of hair

-

23,633 bags of nail clippings

-

18,970 slices of umbilical cord

-

11,431 baby teeth

-

8,619 placentas

Over the past two decades, participants have repeatedly filled in long questionnaires about their health, lifestyle and environment.

Some of the samples that were taken at the beginning of the study are only beginning to show their value now due to advances in technology.

Head of labs Dr Sue Ring said the lab staff take it in turn to carry an emergency phone in case the freezers fail

Head of laboratories Dr Sue Ring, who joined the team in 1996, said techniques had changed in the way DNA is analysed and things are possible today that were not when the study started.

She said: "When we set up the original DNA bank, we initially included one DNA sample from each person but Jean had the foresight to store white blood cells, a source of DNA, from the babies' cord blood and from the children when they were seven, we continued to collect these samples at later time points.

"Having these samples has been incredibly valuable for the epigenetic research we are now working on."

There are almost 80 freezers which contain thousands and thousands of human samples

Dr Ring is also in charge of the freezers, which are all alarmed. In case of power failure, a member of staff is on call 24 hours a day.

The original CO90s babies, now in their 20s, are being invited to take part in two-year clinic, Focus@24+ , to "help researchers piece together the great puzzle of human health" from babyhood to adulthood, with a hope 5,000 people will take part.

Original CO90s babies Charlotte Abraham, 23, and Georgina Searle (right) are taking part in the Focus@24+ clinic

Georgina Searle, 24, has just attended the project's latest clinic session.

"I enjoy taking part in Children of the 90s because I know that all the tests are going into research and this will hopefully help the future generations," she said.

"It's also interesting finding out about all the tests and seeing some of the results, like from the bone and body scans."

Prof George Davey Smith and Prof Paul Burton share the running of the study

When Prof Golding retired in 2006, Prof George Davey Smith took over as scientific director, before he was joined in 2013 by Prof Paul Burton, an expert in big data.

Prof Davey Smith said they were now trying to "future proof" what they were collecting by altering the way samples are stored.

When asked how things had changed, Prof Burton said: "First of all, because the technology and bio-technologies have advanced so much, we now know more about what we can do and we are now able to more precisely target our research at the important questions to be answered.

"Medical research is very expensive and our national funders, the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust, expect us to be effective in producing good output for the money."

A few of the discoveries from the Bank of Life:

People with two copies of a particular gene variant are 70% more likely to become obese

Eating oily fish during pregnancy may improve sight, IQ and positive social behaviour in children

Male biological clock - older men take longer to conceive a baby regardless of the mother's age

All skin creams now list ingredients after link between peanut oil and peanut allergy established

"Getting grubby" by coming into contact with harmless bacteria confirmed as a boost to children's immune systems

Prof Golding said: "When we originally enrolled the women in pregnancy we said that the information they gave us would be unlikely to improve the health of their own children but that it would be beneficial to the upbringing of their grandchildren.

"Fortunately our promise was correct, this piece has highlighted some of the many discoveries made using the information the families have given us which are benefitting the next generation."

The original "babies" from the Children of the 90s get together at an Easter party this March with their own babies

She likened the work to an ongoing detective story.

"I don't think we'll ever understand everything but the more we look at genetics and the way in which the environment and the genetics interact, it looks as though that interaction comes down the generations," she said.

"You can have somebody who is very traumatised in childhood, and if they've got a certain gene, they're more likely to have a really bad outcome. But if they've got another form of the gene, actually it helps and they're stronger and achieve more.

"So, the whole subject gets more complex but very exciting. There's no lack of discoveries."

The Bank of Life is stored in the basement of a concrete office block in Clifton in the centre of Bristol

- Published26 July 2014

- Published10 October 2013

- Published31 December 2011

- Published3 March 2011