Massive star bursts caught in one in 10,000 chance encounter

- Published

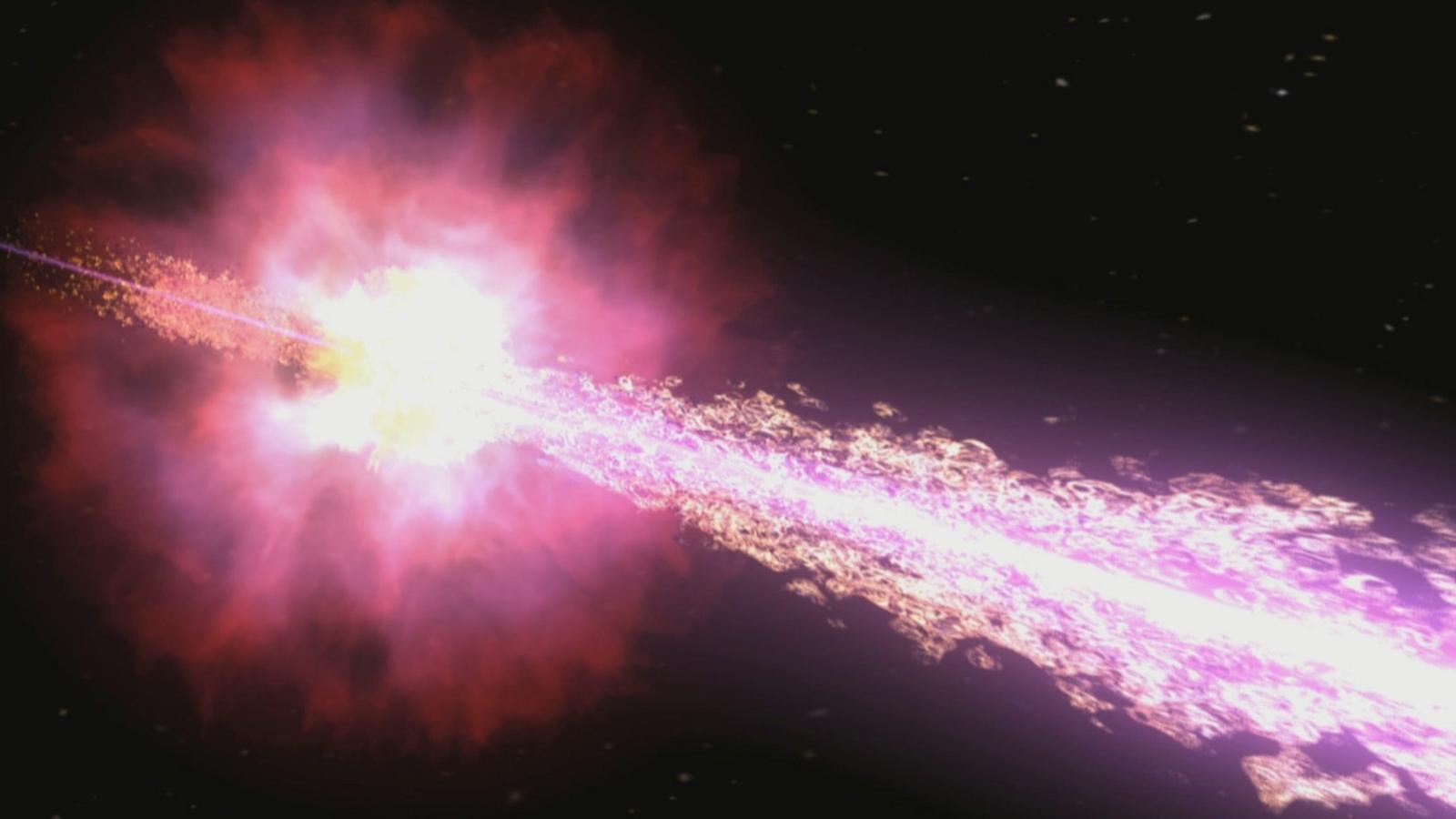

Gamma ray bursts are tightly focused beams of light generated by the collapse of a dying star

A detailed picture of the most powerful type of explosion in the universe has been captured in what was described as a one in 10,000 chance event.

Light from gamma ray bursts (GRBs) was captured by an orbiting telescope developed in part by Bath University.

NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected the short-lived GRB in June last year as a dying star collapsed into a black hole.

The findings help to unravel disputes over the origin of black holes.

Professor Carole Mundell said there had been "intense debate" about the nature of GRBs

A team from Nasa, the University of Maryland and Bath University was able to measure how the light was produced by the material ejected into space during the explosion, and a special property of the light that probes magnetic fields - its polarisation.

Dr Eleonora Troja from the University of Maryland, lead author of the research paper published in Nature, external, said: "If you ranked all the explosions in the universe based on their power, GRBs would be right behind the Big Bang.

"In a matter of seconds, the process can emit as much energy as a star the size of our Sun would in its entire lifetime.

"We are very interested to learn how this is possible."

'Decades of investigation'

The data suggest strong magnetic fields form close to the new black hole and drive energy and material outwards in a tightly focused beam at speeds approaching the speed of light.

Professor Carole Mundell, head of physics at Bath University, said there had been "intense debate" about the nature of these high-speed flows.

The findings also suggest that synchrotron radiation - which results when electrons are accelerated in a curved or spiral pathway - are the key to answering this question.

"This is an important achievement," added Dr Troja.

"Despite decades of investigation, the physical mechanism that drives GRBs had not yet been unambiguously identified."

GRBs were thought to only be found in deep space, but the Fermi telescope discovered all electrical storms on Earth produce the blasts and an estimated 1,100 occur each day.

Atomic records found in ancient cedar trees in Japan and in Antarctic ice showed the energy from a GRB hit the Earth in the 8th Century.

- Published16 December 2014

- Published21 January 2013

- Published21 November 2013