Natasha Abrahart suicide: Parents say she 'wasn't helped'

- Published

An inquest found Natasha took her own life partly as a result of neglect

Natasha Abrahart was studying physics at the University of Bristol when she took her own life. Her parents have told the BBC how they are still struggling to come to terms with her death.

Robert Abrahart is standing in the middle of Natasha's bedroom at the family home in West Bridgford, Nottingham. It is just as his daughter left it.

"After six months, we've still not got around to doing anything. Nobody wants to come up here, is the truth," he says, his voice slightly cracking.

"She used to sit in that corner playing the cello," Natasha's mother Margaret says, pointing to the musical instrument still in its case in the corner of the room.

"I think I find it really hard to think that she's gone," she adds.

"It's sort of unreal and unnecessary," Robert says. "One minute you've got a daughter, the next minute you haven't."

"What a waste," agrees Margaret. "You have to accept it somehow."

Natasha, 20, died in May 2018, towards the end of the second year of a physics course at the University of Bristol.

An inquest earlier this month heard she suffered from social anxiety and found she took her own life partly as a result of neglect by a local NHS trust.

Natasha was a keen musician who played the piano and cello

The coroner ruled Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership Trust (AWP) "underestimated" her condition and that there was a "gross failure" to provide care.

He also said NHS guidelines over follow-up appointments with patients identified as a suicide risk were not followed.

The inquest heard Natasha had told university staff about a previous suicide attempt. But the coroner was not critical of the institution, where there have been at least nine student suicides in the past three years.

Despite this, the Abraharts are unhappy with the care she received from university staff and have said they are considering legal action.

They say Natasha's social anxiety had begun when she was young, although they thought her shyness was a phase that had passed.

Natasha's parents say she was "quite shy" when she was growing up

"Natasha was a very easy child to look after," Margaret says. "She was quite shy from quite early on... she used to play quite a lot on her own.

"But then her brother came along. She absolutely loved her brother.

"At one time I wondered if she might need a bit of help with the shyness but she began to grow out of that."

In fact, her parents say, Natasha grew up with lots of friends. Her birthday parties, they say, were well attended.

Natasha excelled at school and chose Bristol University because of its "prestige".

Her parents say she settled in well in the first year, when she lived with four others in halls of residence.

But in the second year she moved into a house-share which meant she was "a bit further apart" from friends, according to her friend, Hope White.

It was in this year that Natasha fell behind with her work.

Another friend, Luke Unger, had lived with Natasha in the first year and described her as "very calm".

Luke Unger says Natasha told him she feared being "kicked off" her course

In the week before she took her own life, she met him for dinner at a restaurant in the city centre.

"She said 'I'm failing all my exams, I've got this exam coming up, I just don't think I'll do it,'" he says.

At this point she admitted she feared being "kicked off" the course and missing out on her ambition of taking a masters degree.

"I could tell she was really, really stressed so I said let's go for dinner next week," Luke adds.

She agreed, but it never happened.

"That was three days before she died."

Her parents said they had first become aware of her concerns about failing her course in January 2018.

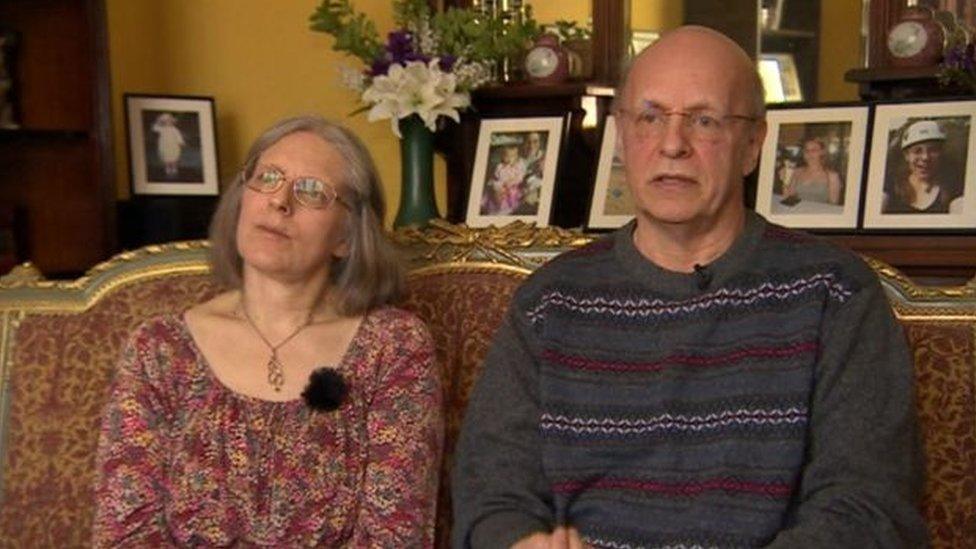

Margaret and Robert Abrahart say they are considering taking legal action against the university

On 20 March 2018 one of Natasha's flatmates phoned her parents to tell them she had tried to hang herself. They spoke with Natasha, who told them she had been "silly" and reassured them.

But on 1 May her parents were visited by a police officer and told that their daughter was dead. She had been found hanged at 14:30 BST on the previous day.

Margaret says Natasha would have needed to have been very distressed in order to ask for help in the first place.

"Natasha was one very much to sort out her own problems and I can't think of a time in her life when she asked for help - but she asked for help and didn't get any," she says.

After her death, Natasha's father logged into her email account and found an email she had sent to a member of staff in the physics department.

"I wanted to tell you the past few days have been really hard, I've been having suicidal thoughts and to a certain degree have even attempted it," she had written.

Margaret and Robert Abrahart say their daughter got no help from the university when she asked for it

The inquest into her death heard staff at the university were aware of and had discussed her mental state.

The university said its student administration manager had met with Natasha "on many occasions to offer support and advice", including taking her to the university GP.

It added that options had been discussed to "alleviate the anxiety she faced" about a planned presentation to her peers, as part of an assessed laboratory conference.

She died shortly before she was due to do her presentation as part of her degree.

Although Natasha told friends she feared being thrown off her course, this was not something that the university had discussed with her, it said.

"At no point had Natasha been threatened with failing her course," the university said in a statement.

"Natasha's death is a tragedy that has affected everyone at the university, particularly the staff and students who knew and worked with her in the School of Physics," it added.

Robert Abrahart says he is determined to "put the systems in place to fix" the way people like Natasha are treated in future.

"We left it to professionals and it turns out that was a mistake," he says.

Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership Trust has paid damages to the Abraharts after admitting it missed two opportunities to put in place an appropriate management plan for Natasha.

The coroner also criticised the university GP who prescribed Natasha the anti-depressent Sertraline.

Dr Emma Webb had told the inquest the student health service's procedure in such a case was to wait two weeks before a follow-up appointment.

But the coroner ruled Dr Webb failed to follow NHS guidelines that said patients identified as a suicide risk should be seen within a week.

Asked why she had not referred Natasha to the vulnerable student support service, Dr Webb said AWP had been leading and co-ordinating her care.

Hope White says the university did not help her after her friend's death

Natasha's friend and former flatmate, Luke, says life at the university can be one which sees students fail for the first time in their lives.

"I think definitely at Bristol University there are pressures to perform academically," he says. "You are surrounded by people who would have been the smartest in their schools, and the most competitive.

"And when you're not achieving in the way that you want to, and the way that you have been, it can be really degrading."

Natasha's friend Hope said she had been badly affected by her death but the university had not helped her.

"I approached the wellbeing officer from the university asking whether I should talk to someone," she says.

"I was in quite a dark place after Natasha, and because it was near the end of the year they told me to turn to my friends and family and if I still felt bad to come back at the start of the year because everyone was leaving now.

"I didn't feel too supported by the university. I think [it was] a toxic year for most people from all of these student suicides."

If you have been affected by this story then BBC Action Line have a list of organisations who may be able to help.

This story will be featured on BBC Inside Out West at 23.35 GMT on Thursday 30 May.

- Published21 May 2019

- Published16 May 2019

- Published14 May 2019

- Published13 May 2019

- Published10 May 2019

- Published9 May 2019

- Published8 May 2019

- Published7 May 2019

- Published26 February 2019

- Published29 October 2018

- Published11 October 2018

- Published22 August 2018