Toppling Bristol's Edward Colston statue: How do people feel now?

- Published

Bath entrepreneur Manoel Akure stood on the vacant plinth and shared his life experiences with the crowd

It has been a year since the statue of slave trader Edward Colston was pulled down in Bristol during a Black Lives Matter protest. The act was triggered by the death of George Floyd, with protests across the world calling for an end to racism.

Since then, statues in other countries that reflect colonial histories have been pulled down too, and a survey has been launched to see what the public wants to do with Colston's statue permanently. But how did its removal affect people in the city?

"It was an important part of history, something I'll be telling my grandchildren about," said DJ Angel Mel

'I reclaimed my identity'

Bristol DJ Angel Mel, 41, said the event had given her greater insight into her identity.

"I had people that I have known since primary school ask me questions about my life and experiences that they've never done before and I had to learn how to answer them.

"It was a powerful important part of history, something I'll be telling my grandchildren about.

"We are still talking and we will always talk about it I think.

"Every time I walk past that plinth I remember what happened and how it divided the city and how we are now in a process of healing."

The DJ said she was struck by how peaceful the policing had been that day compared to during the Kill The Bill demonstration when violence broke out on 21 March.

"I don't condone cancel culture, however I think we should welcome change," said Conservative activist Samuel Williams

'I feel anti-climactic'

Bristol conservative activist Samuel Williams, 34, said he was disappointed there had not been "substantial change" in thinking around race relations since the statue came down.

"Looking back, I feel very anti-climactic about it all.

"In principle, I'm not in favour of pulling down statues, I don't condone cancel culture, however I think we should welcome and encourage the political activism and voice of the people especially of those who are underrepresented.

"The pulling down of that statue was all of our responsibility and unfortunately it happened because people didn't feel listened to.

"Since then, we still don't have representatives who listen and learn, because of this, we will continue to see these types of lawlessness."

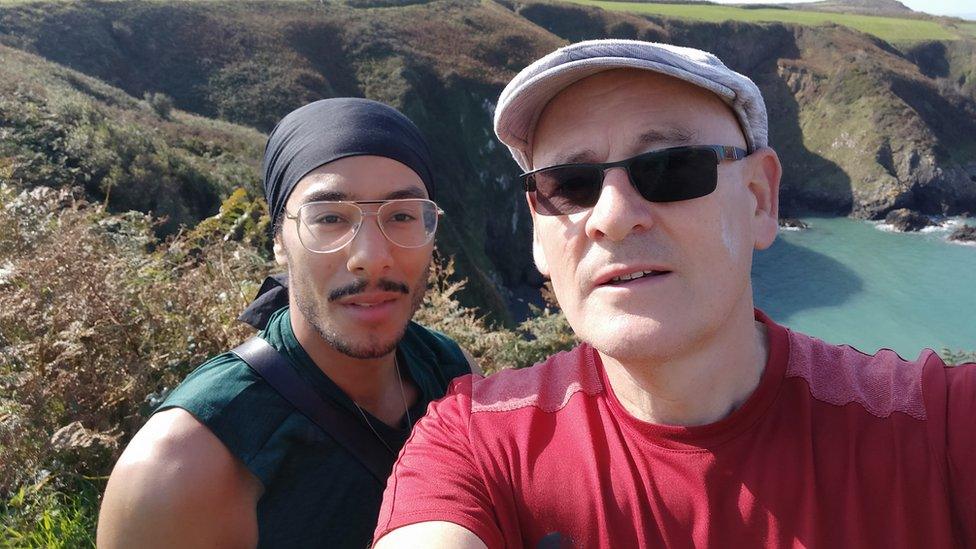

"I've always felt uncomfortable about statues and signs of the empire and colonialism on the streets," said John Ridley whose children are dual heritage

'I feel validated'

Retired Bristol head teacher John Ridley, 63, said the forced removal of the statue was a tipping point in how the city thinks about racism that "we can never go back from".

He said: "My conversations with friends and family changed.

"My wife is black and my children are dual heritage, so I had a lot more conversations with them about their experiences.

"It's deepened my understanding of what it's like to be black in the UK.

"I've always felt uncomfortable about statues and signs of the empire and colonialism on the streets.

"I always felt like I was a minority in this view, so since that day last year I've felt validated in my unfavourableness with them.

"When I walk past that plinth I feel proud of Bristol."

"That year I felt like I really didn't know who I was, where my place was in the world," said artist, Manoel Akure

'Objects mean nothing'

Bath entrepreneur and artist Manoel Akure, 20, found himself on the plinth the day Colston's statue came down.

"That day changed my interaction with the rest of the world.

"On the day, I found myself on the plinth telling a few stories of my experiences in an attempt to give hope amidst a very pensive period.

"That year I felt like I really didn't know who I was, where my place was in the world, so that time made me really reflective.

"Is the part I'm playing promoting the world I dream of?

"Objects don't mean anything when it comes to people actually changing.

"Since then I've been focusing more on learning from people and ideologies that I've not understood, and I've been trying to focus on my circle of influence to change people's perspectives and to talk about what part they play in the bigger picture."

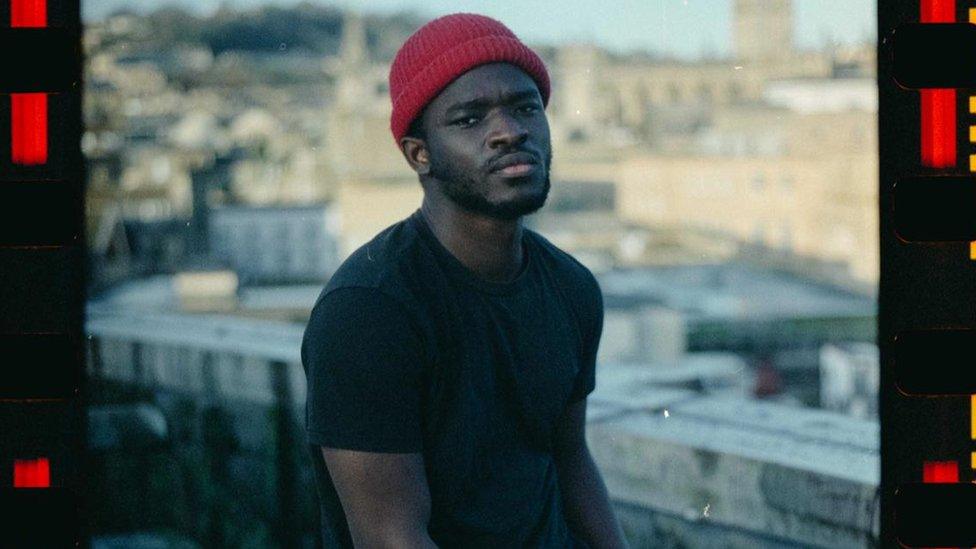

"We were marching to end racism, and that's what it should be about rather than talking about Colston's statue," photographer Khali Ackford said

'I know my purpose'

Bristol Photographer Khali Ackford said the day the statue came down affected his personal and working life.

"I feel like I know now what I need to do. I was already focused on giving black people a positive reflection of themselves, so it's concentrated my work and my purpose.

"Colston coming down was huge, and even though Bristol was already on the map, it really resonated with the world. It was a massive statement.

"But what's more important were the reasons why it happened in the first place. We were marching to end racism and that's what it should be about rather than talking about Colston's statue."

"This global phenomenon happened where the whole world realised that racism exists and there was a great pain that came with that," herbalist Elsie Harp said

'Where power lies'

Bristol-based herbalist and mental health practitioner Elsie Harp, 33, said she developed a "stronger sense of community" in the wake of the statue's removal.

"Prior to the statue coming down I had friends of colour but they were much more disparate, and since I have made some really incredible connections.

"This global phenomenon happened where the whole world realised that racism exists and there was a great pain that came with that.

"I do now feel much more held in my discussions around racism and how that impacts on my life and my sense of self.

"The Colston statue was supposed to be pulled down years ago and it was only through direct action that occurred, and that says a lot for social action and where power lies."

"The violence that day was unnecessary," said law student Robert Graham

'I still worry'

Bristol law student Robert Graham, 26, said ever since the statue had been removed he had been worried that it could prompt other similar actions.

"The people who did it should be prosecuted.

"Changing the names of things and pulling down statues is not going to change history.

"The violence that day was unnecessary and I still worry that this will happen again."

Four people are accused of causing criminal damage to the statue and will face trial in December.

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published14 December 2020

- Published1 October 2020

- Published25 September 2020

- Published16 July 2020

- Published11 June 2020

- Published8 June 2020

- Published7 June 2020