Engineering 'must change' to include everyone

- Published

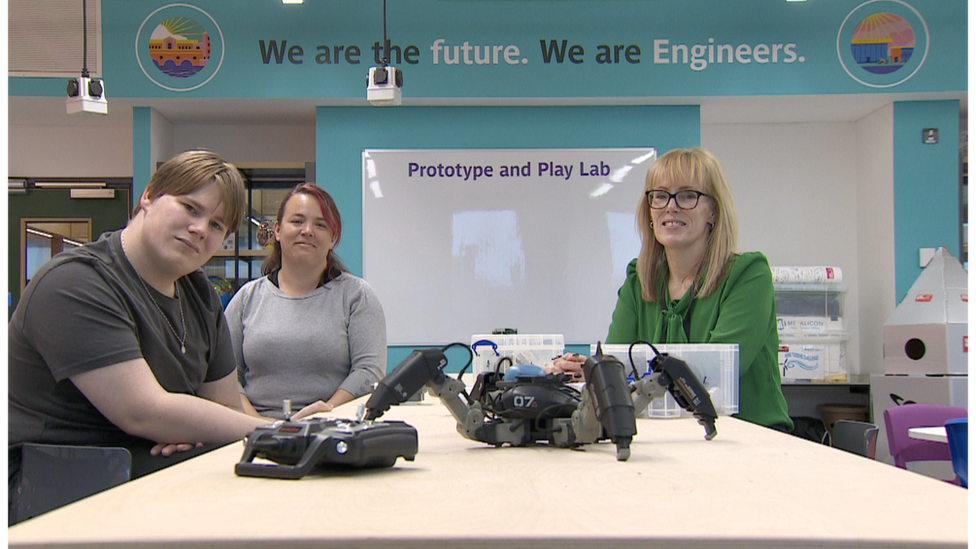

A student, a graduate and a Professor of Engineering

There are numerous schemes designed to attract more women to study engineering, and work as engineers. But one university is going further, changing the way it teaches to break down barriers for students with autism, and other conditions known as "neurodiversity".

Thomas Dixon has always loved taking things apart, to see how they work.

He told me that as a child, he "grew to like all the complexity to it, actually making something so it works and then benefits humanity."

But as well as a gift for technical problem solving, Thomas was born with autism. He is highly sensitive to noise and other sensory stimuli. So a typical engineering workshop can be, for him, "a nightmare".

"My disability just means I have to do things differently", says Thomas Dixon

"I can't be in rooms with a lot of machines running at once, it's just too much for me to cope with," he explained.

Large classrooms with 20 or 30 students all working and talking at once also overwhelm his senses.

Walk around most engineering classrooms in a university, and that is just what you see. Lots of rooms full of machines, students, noise and bustle.

But at the University of the West of England (UWE) they've just built a brand new engineering building, with people like Thomas in mind. Alongside traditional large workshops, there are small spaces for people to work in small groups or on their own.

Prof Lisa Brodie believes engineering must change to attract different kinds of students

Other rooms are being designed with input from students with autism, often surprising the staff. Prof Lisa Brodie runs the department, and she showed Thomas a new quiet room designed to give them space just to chill out.

What she hadn't noticed was the white walls and bright tube lighting.

She said: "Thomas told me it was horrible, and said 'you do realise there is a form of torture called whitewashing.'"

For somebody with autism suffering a sensory overload, a brightly-lit white room is no respite. So they brought in new lighting, with controls allowing people to change the colour. Soft beanbags and other relaxing furniture was introduced.

"We won't get it right first time," explained Prof Brodie, "but what matters is we work with the students to make it right for them."

Prof Brodie insists that meeting the needs of students like Thomas is not just about equality. Engineering needs them.

She said: "If we keep bringing the same type of people into engineering, we'll just carry on getting the same sort of solutions."

There's also a strong drive to attract more women into engineering at UWE. And that means changing people's perception of what an engineer is.

"When I was growing up I didn't know what engineering was," Laura Dixon said.

"I thought it was just for boys, and just about fixing things, repairing cars."

Laura Dixon said she thought engineering was just for boys

It was only when Laura came to UWE aged 28, as a mature student, that she found engineering could be about people, as well as machines. She thrived, and now leads the maintenance engineering team at First Bus.

"Maintenance engineering is all about managing people, managing the workshop. I do sometimes get under a bus, get oily, but only to see what a problem is. That's a small part of my job."

Ms Dixon is now actively encouraging young girls to consider engineering as a career. "Fifty per cent of the world are female, so if we're not in the room, we won't cater to half the population with the things we design."

The new building is bright and airy, with many social spaces for collaboration. For Laura, the spaces she likes are vibrant, busy, noisy even. Often the exact opposite of what works for Thomas.

The new building therefore has to provide different spaces, different atmospheres, for different students.

As Thomas explained it: "A disability doesn't mean you can't do something, it just means you have to go a different way. It doesn't mean I can't do engineering, I just have to learn in a different way."

Despite many years' experience teaching engineering, Prof Brodie says she is still learning how to teach different kinds of students.

"If I've got a neurodiverse student who struggles with noise and sound in a laboratory, I need to find a different way to teach them. But absolutely they can do it, often better than the rest of us."

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published26 October 2021

- Published2 November 2019