Weston man scales Kilimanjaro in memory of baby son

- Published

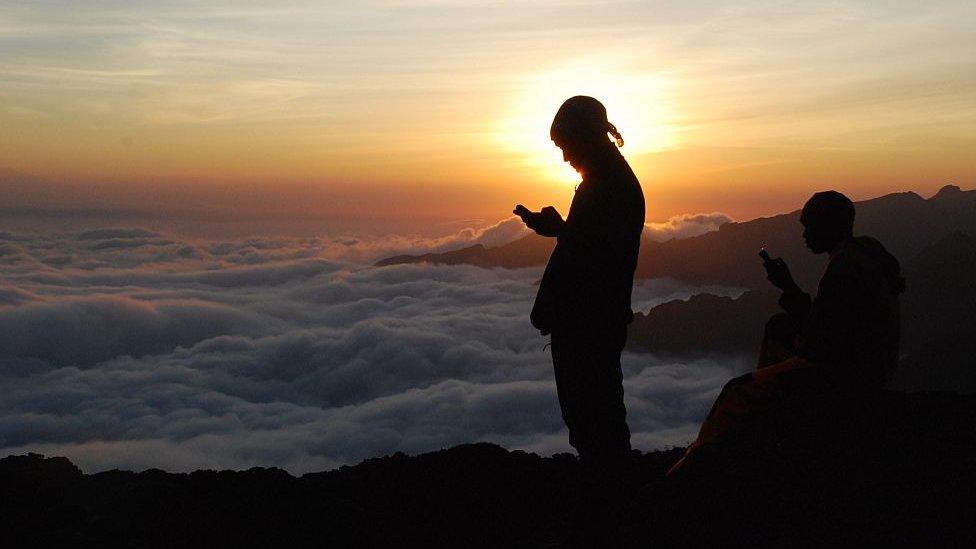

Terry, left, said he was close to giving up on the day he reached the summit

A man who scattered his baby's ashes at the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro said he wanted to "keep his name alive".

Terry Devine took on the 19,340ft (5,895m) peak in Tanzania in memory of Jacob, who died in 2017 at just five days old.

Mr Devine, a lecturer at the University of the West of England (UWE) in Bristol, said he was "physically broken" as he approached the summit.

He reached it on the day he celebrated being 10 years clean of drug addiction.

Mr Devine, 46, and his wife Karen were told two weeks before Jacob, their second child, was born that he was healthy and all was well.

The couple, from Weston-super-Mare, had planned a home birth, having had their daughter surprisingly but safely at home, before things suddenly went wrong.

Jacob was treated in the neo-natal intensive care unit (NICU) at St Michael's Hospital in Bristol

"I could see the midwife's face and I knew something was wrong," he said.

"Then she said 'we've got a breach' and then absolute chaos broke out, as you might expect."

Jacob was starved of oxygen at birth, but staff could still detect a heartbeat and he was rushed to the Neo-Natal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at St Michael's Hospital in Bristol, where he spent the next five days.

But he could not be saved, and Mr and Mrs Devine had a final few moments with him before he died.

"It just robs a part of your soul which you never get back," said Mr Devine.

Strength from addiction

Since suffering the bereavement, Mr Devine has taken on a charity challenge every year in Jacob's memory, to raise money for Cots for Tots, the dedicated charity for the NICU at St Michael's Hospital.

Mr Devine and fellow fundraisers trained in Wales before finally standing at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro in September.

"It takes your breath away," said Mr Devine, whose ascent and descent of the peak took six days.

The family had five days with Jacob before he died

He said that earlier times in his life, when he "went off the rails" and became addicted to heroin, helped give him the mental strength to cope with the physical test.

"I was a street-level heroin addict for 20 years - homeless, using needles, everything that goes with it.

"I've spent the last 10 years sorting my life out, you could say in that time I've gone from addict to academic."

But when it came to summit night, Mr Devine said even he was tested to the limit.

Mr Devine took on the challenge in aid of the Cots for Tots appeal

The plan was for the group to get up at 23:00 BST and start walking, but Mr Devine did not manage to sleep ahead of taking on the rocky incline to the summit.

"One of our team, called Mark, pulled out at that point, he was becoming delirious.

"An hour or so later, I got to the verge of giving up myself.

"One of the other walkers, called Mel, turned to me and said 'Terry, it needs to be you at the top of the mountain that spreads your son's ashes'.

"That really hit me, and at the same time the sun started coming up, it felt like the universe was saying 'I've got your back'.

"One of the porters asked me if I could commit to another 30 minutes, and I decided I would do that, then turn round and go back down, and people would appreciate I had done as much as I could."

That 30 minutes turned into another seven hours, but Mr Devine did make the summit, achieving his goal of climbing Kilimanjaro 10 years to the day when he first entered a drug recovery programme.

"I sneaked off by myself. I had some of Jacob's ashes and I had a moment with God, with the mountain, with my son. I had a good cry, as you can imagine."

'The pain is always there'

Mr Devine said recovering from drug addiction, and the vulnerability that comes with talking about it, had helped him and his wife, but he said the pain of losing a child has never left them.

"From that day [of Jacob's death] if anyone I'm close to dies, it gets into your soul, it awakens part of you, to do with loss," he said.

"It's always there.

Mr Devine said he had spent the past decade "sorting my life out"

"People said to me, when we lost Jacob, that time is a great healer but personally I don't believe that," said Mr Devine.

"I know other people who lost children, and to this day they're still broken by it.

"I believe it's what you do with that time which will determine the healing."

The pain of losing Jacob "is always there" said Mr Devine, but that recovering from drug addiction had helped talk about his feelings

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk

- Published3 November 2022

- Published7 October 2022

- Published22 August 2022

- Published20 April 2016