Hotels and bars need more EU workers, say bosses

- Published

Hospitality workers demonstrate outside Parliament

Hotel and bar managers have condemned a government decision not to fast-track visas for European workers.

Official figures show hospitality vacancies have risen by 72% since Brexit, while the number of EU workers in the industry has fallen by 26%.

"We are missing that vital injection of... wonderful people that came before Brexit," one Bristol bar owner says.

But ministers insist hospitality firms should recruit British workers instead of relying on "cheap foreign labour".

Sam Espensen says she can't replace her European bar staff

Sam Espensen, owner of Espensen Spirits bar in Bristol, provides the special drinks at weddings and parties, events and festivals. Her raspberry gin has won awards. But she is finding it difficult to staff big events.

"We've had Italian chefs, we've had French bartenders, I had a wonderful Portuguese guy who would come and do weddings and events bars with me. All of them left because of Brexit, and none of them are coming back," she said.

"Many say that when Covid lockdowns began, EU staff went home to be with family. When the rules were relaxed, they stayed home because it had become much harder to work in the UK."

It sounds plausible. Is it true?

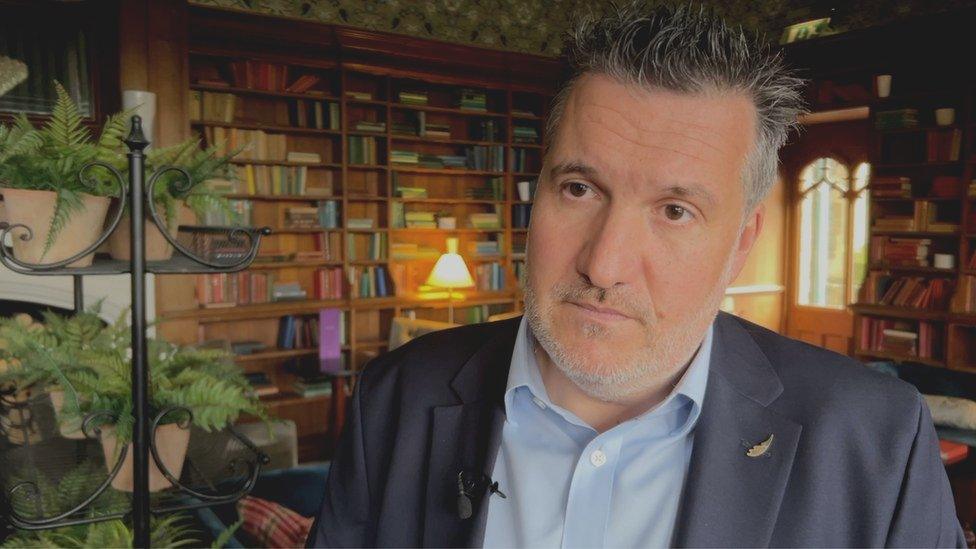

"We are struggling for staff", says Raphael Herzog of Bristol Hoteliers' Association

At a four-star hotel in the South Gloucestershire countryside, I met Raphael Herzog, who chairs Bristol Hoteliers' Association.

"We are still struggling, to be honest, to recruit people," he told me.

In 2019, there were 85,000 hospitality vacancies. By the end of 2022, this had risen to 146,000, up 72%.

Mr Herzog is clear where the gap comes from.

"We used to have about 45% of our staff from the EU, now that has fallen to just 25%", he said.

"It is so hard for people to get a visa to come here, we need the government to work with us to improve the immigration route."

Raphael Herzog talks to his chef at a hotel near Bristol

There is no doubt hotels, pubs and restaurants are short of staff.

But is Brexit to blame? Or Covid? Or something else?

Independent experts at the Office for National Statistics have tried to find out.

Officials analysed the number of people on payrolls, external throughout the period of Covid lockdowns and the post-Brexit deal with the EU, since 2020.

They found that as lockdowns took effect all payrolls fell, even when people on furlough were included.

However, as restrictions eased the numbers employed went back up again, with one exception.

EU workers remained below 2019 levels. And hospitality was the worst affected sector.

"The largest decline in total payrolled employments was seen in accommodation and food services; this was driven by a 25% (98,400) fall in payrolled employments of EU nationals during the two years up to June 2021," the report's authors found.

Mr Herzog has a clear solution. Hospitality, he argues, should be recognised as an occupation "in shortage", and people fast-tracked for visas.

Since Brexit EU workers, like all foreigners, need a skilled worker visa to take up roles such as chefs.

That means a specific job offer from an employer at £26,200 pa or more. But there is a list of occupations with a recognised shortage, and the hospitality industry wants to be on it.

Mr Herzog said: "This is the only way to ease the process for us to recruit again from the EU. Or from elsewhere, we don't mind."

The Shortage Occupation List, external is compiled with advice from independent academic experts, the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC). They have recently published new advice on exactly this question.

Should hospitality be on the list?

They recognise there is a big shortage of hospitality workers, and a drop of 26% in workers coming from the EU.

But they advised against adding chefs and other hospitality occupations to the official list.

Why? Primarily because pay is too low.

The MAC report, external says: "There still appears to be little progress in improving terms and conditions, and in particular pay growth continues to be driven to a large extent by the statutory minimum wage."

In other words, if so many hospitality jobs are paid at the legal minimum wage or just above it, can they be considered skilled jobs? If not, then why do employers need to import special staff, rather than simply train up British workers?

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, defended this decision in the recent Budget.

He said: "What those people who voted for Brexit want is an economy that does not depend on unlimited, low-skilled migration, but invests in our skills here."

At one Bristol tourism hotspot, they are doing just that.

A surfer at Bristol's artificial surf centre, The Wave

The Wave is the South West's first artificial surfing lake, just outside Bristol. Complex machinery creates near perfect surfing waves.

And unlike the sea, they come like clockwork.

There's a steady stream of surfers here, and most head straight for the café afterwards to refuel.

Its head chef has also seen EU staff head home. Dan Ashford called it "an exodus", when I met him.

But without his French and Spanish surfer cooks, he has turned to West Country workers.

Dan Ashford (left) and his team at The Wave kitchen

"We are doing everything we can to motivate them," he explained.

"We have nine hour shifts, not split-shifts. Paid breaks, holidays, training and motivation."

He introduced me to the team preparing for the summer season.

"Most of these guys have come back for the third season in a go, so we must be doing something right."

Across hospitality, there are training schemes like this running. Colleges offer new courses and prestigious hotels are taking on apprentices.

But, says Mr Herzog, it is still not enough: "We need everything now. Training yes, but also more people from abroad. We need to help grow this economy and we cannot do that without people."