Student suicides: Petition calls for universities to do more

- Published

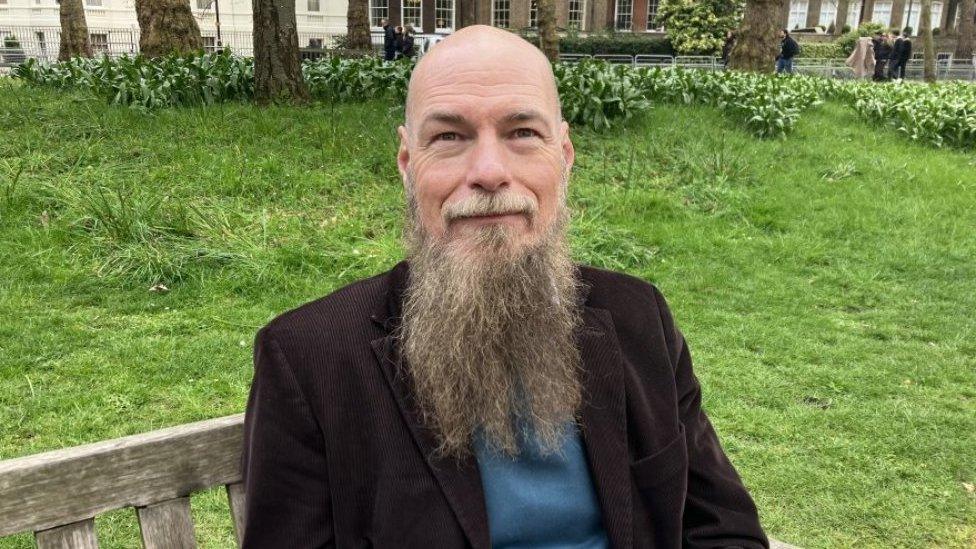

Duncan Abrahart wants universities to have a statutory duty of care to students

The brother of a young woman who took her life while studying wants universities to be made legally accountable for students' welfare.

Natasha Abrahart, from Nottingham, was just 20 when she died in April 2018.

She suffered from social anxiety and took her life on the day she was due to give a presentation in a large lecture hall at Bristol University.

The university said it had worked "incredibly hard and diligently to support" her.

Her brother Duncan wants universities to "make sure that their policies and procedures are actually safe".

Around 100 students die by suicide every year, and a group of families who have been bereaved started the #ForThe100 movement in an attempt to get greater support for vulnerable young people.

Mr Abrahart, 23, was among campaigners who gathered at Downing Street earlier to urge the government to impose a statutory duty of care upon universities towards students.

A petition set up by the campaign attracted 128,293 signatures, passing the 100,000 mark needed to trigger a debate in Parliament.

'Students over 18 need care'

The petition said: "A duty of care already exists for staff, and for students under the age of 18 in higher education.

"There should be parity in duty of care for all members of the higher education community.

"This is not a petition for 'in loco parentis' or for duplication of the NHS. We only seek parity and legislative clarity on duty of care for all students."

Natasha had social anxiety disorder, which was classed as a disability under the Equality Act

Speaking to BBC West, Mr Abrahart described his older sister as "incredibly caring", adding that she was like "a second mother" to him.

Asked about the changes he wants to see, he said: "I want accountability for universities.

"I want them to make sure that their policies and procedures are actually safe and what they are choosing to offer is communicate to the students."

Mr Abrahart emphasised that some universities do have a strong track record on mental health, but described the disparity between what institutions provide as "horrific".

Many universities have said imposing a statutory duty of care is unworkable because students are young adults.

In a response to the petition, the Department for Education said: "Higher Education providers already have a general duty of care not to cause harm to their students through their own actions.

"We acknowledge the profound and lasting impact a young person's suicide has upon their family and friends, and know among the petitioners there are those who have personal experience of these devastating, tragic events.

"[However] we... feel further legislation to create a statutory duty of care, where such a duty already exists, would be a disproportionate response."

Natasha Abrahart, from West Bridgford in Nottingham, took her own life at the age of 20

Mr Abrahart said: "If I were an 18-year-old and I went straight into the workplace, I would be protected under and employment duty of care. At university I don't have that.

"There is immediate parity between being a university student who's an adult and being someone who is in the workplace and an adult.

"If I am in the workplace, I will have more legal rights than I ever will at university."

'Clarity for students'

Lee Fryatt, whose son Daniel took his own life in his first year of his studies at Bath Spa University in 2018, said a change in the law would give students and their parents "clarity".

Mr Fryatt, from Bournemouth, said the government's assertion that universities already have a general duty of care towards students was too vague.

"What a statutory duty of care will provide is a legal framework and clarity for the students and their families, and also for academics and higher education institutions themselves,"he said.

Mr Fryatt said that a statutory duty of care would lead to universal standards of training for university mental health teams, and also set out a framework of when parents should be informed.

He said this would give university staff more confidence to talk about mental health and "recognise opportunities to intervene".

Lee Fryatt said a change in the law would give students and universities "clarity"

Last year, Natasha Abrahart's family took legal action against the University of Bristol under two types of law - the Equality Act 2010 and also the law of negligence.

They won their claim under the Equality Act because her social anxiety disorder was classed as a disability.

The judge ruled the university had not made reasonable adjustments in the way she was assessed as part of her course.

But they lost the negligence part of the case because the judge was not satisfied that the university owed Natasha a duty of care.

His judgment noted that "there is no statute or precedent which establishes the existence of such a duty of care owed by a university to a student".

Since then, Natasha's family have campaigned for a change to the law.

'We care deeply about students'

A spokesperson for the university said it extended its "sympathies to her friends and family" and that it had worked hard to support her.

This "included offering alternative options for her assessments to alleviate the anxiety she faced about presenting her laboratory findings to her peers".

"Every single member of staff cares deeply about the welfare of our students and, as with all universities, we provide a wide range of pastoral support services which they can easily access," the spokesperson added.

"Part of this support involves assisting students to access specialist care under the NHS or other providers should they need it, as happened in Natasha's case."

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published16 March 2023

- Published5 March 2023

- Published7 October 2022