How an unmarked World War One grave in Bristol reunited a family

- Published

Members of Harry Dunn's family from Bristol and South Wales joined a rededication ceremony by his grave at Arnos Vale Cemetery on Tuesday

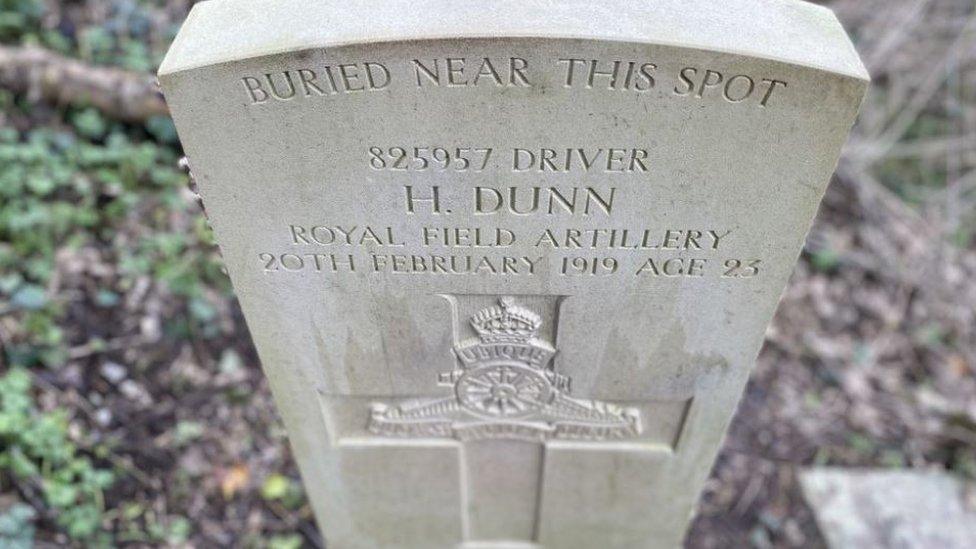

When historians first discovered the grave of a "forgotten" World War One soldier in a Bristol cemetery in 2004 they had no idea who he was.

But after the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) created a new headstone for serviceman Harry Dunn and appealed for information, a fascinating story began to emerge.

The piecing together of a lost family history has seen Mr Dunn's descendants on different continents reconnect decades after his death, and there is now an officially recognised resting place for the soldier.

The sparkling new headstone at Arnos Vale cemetery lies a few feet from the remains of Driver Harry Dunn, from Brislington, Bristol, who died from pneumonia in 1919.

Although narrowed down to a couple of metres, the exact location of his grave has not been confirmed.

But for his newly-acquainted descendants from Canada, Bristol and south Wales, it is enough that he is properly acknowledged at last.

Mr Dunn enlisted in the South Midland Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery in 1915 and served in France and Belgium on the Western Front until 1917, when he was transferred to Italy.

His death, aged 23, came a few days before he was due to be discharged and meant he was eligible for a Commonwealth War Graves headstone as a war casualty.

Simon Bendry from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission said finding Harry's living relatives had been a 'remarkable' experience

For decades his name was acknowledged only on a memorial in Brookwood, Surrey, reserved for servicemen who died in the UK but whose burial location was unknown.

Now after years of neglect, the grave has been properly marked and visited by relatives of Mr Dunn reunited by the appeal.

Family from Bristol and south Wales were joined by members of the Royal Artillery for the official rededication service on Tuesday.

Other relatives from Canada hope to make the trip to pay their respects soon.

The search for Mr Dunn's living relatives started in 2023 and reached Andrew Keepin, who lives in Cwmbran, after a colleague saw the story go out on BBC Points West.

Mr Keepin described events since then as "a whirlwind".

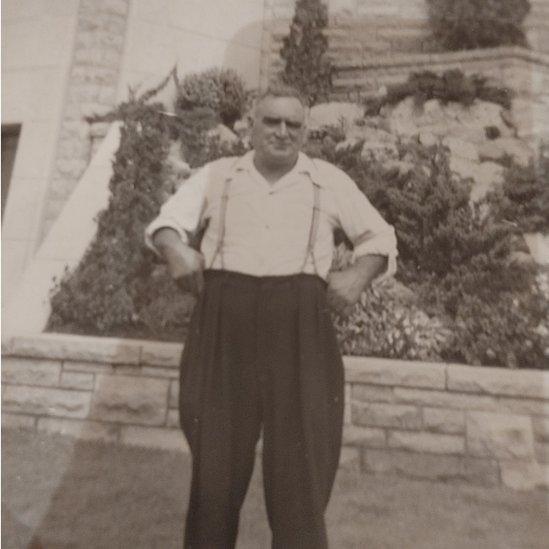

Reg Keepin (left) and his son Andrew are Harry Dunn's cousins once and twice removed

"Three months ago we had no idea of Harry or his siblings. We only knew of a Florence Keepin (Harry's mother), one of 15 children," he said.

"Now we know Harry's full history, the battles he fought in across Europe, what happened to his siblings when his mother and father died, a full back story," added Mr Keepin.

The CWGC had investigated Mr Dunn's history after the grave was first found 20 years ago but did not have any contact details for any Dunn or Keepin until the BBC's appeal aired.

"Now we're able to tell his story and he's now got a grave so we can visit and pay our respects," said Mr Keepin.

"Also, we have a whole family that we knew nothing about and they live in Canada. That's pretty amazing," he added.

Harry Dunn died just a few days before he was due to be discharged

They have now been able to piece together what happened to Mr Dunn's family at the start of the 20th Century, which offers a fascinating insight into life at that time.

The 1901 census found him living with his grandmother Caroline Keepin in the centre of Bristol while his mother, Florence, lived nearby with brother William and sister Alice.

Their father had recently passed away and what the census does not show is that Florence was in the early stages of pregnancy with another girl.

Florence Elizabeth 'Bessie' Dunn would be born later that year.

Dunn children orphaned

Life was tough and documents show that Mrs Dunn worked hard to look after her four children and although the community helped out, the children were always malnourished.

Sadly she was to die in 1909 from dropsy, (today referred to as oedema), leaving the four Dunn children as orphans.

Harry Dunn then went to live with his uncle Albert Keepin in Brislington until war broke out.

A letter unearthed by the family shows his three siblings were placed with relatives until a long-term decision could be made over their future. .

William and Alice were taken in by Barnardo's and left for Canada in 1909 and 1910 as part of the 'Home Children' programme.

'Family decimated'

The youngest child, Bessie, went to live with her uncle John Keepin in Newport before moving back to Bristol in the 1920s.

Mr Keepin said: "The family were decimated and in different parts of the world.

"We've recently made that connection with the Canadian Dunns and found out that that they've really flourished, a number of them live in Kingston, Ontario."

William was placed at a farm in Sydenham near Kingston, while Alice was sent to Toronto.

His grandson George Dunn, who also lives in Kingston, remembers his family talking about the two children coming across on a ship.

He said: "I remember them talking about that kind of an ordeal, and how we lived in a farm in Sydenham at 10 or 11 years old and William slept in the barn.

"He really wasn't treated all that well as a child coming here from England. He was just given scraps and wasn't dressed properly.

"Our Canadian winters get very, very cold and I remember my mom talking about that. And just how could someone treat a child like that."

Harry Dunn's brother William was sent as an orphan child to start a new life in Canada

Since being alerted to their link with Harry Dunn, the family in Canada have been sifting through old letter and photographs.

They have discovered letters written by Bessie to her estranged brother and sister.

In them she describes how she would love to come and visit them but cannot afford the boat fare.

Another of William's grandchildren, Beth Vanderhelm, who also lives in Kingston, said: "Our aunt had brought over some photo albums for us to look through and these letters were in the back, and it was amazing.

"They're almost 100 years old and written in pencil, and they still survived.

"Just reading them it broke my heart when Bessie said, 'I miss you so much'.

"I would have loved to have found the money to bring her myself, you know, but it was nice to know that later on in life she did meet someone and had her own family."

The Keepin family say their quest for information is only just beginning

When Harry Dunn died, records show that his medals were sent to William in Canada.

George remembers his father speaking about them.

He said: "My dad actually built a shadow box for them to be in. It had purple felt in it.

"But after that there's been nothing, we don't know, so at this point we don't know where the medals are, but I do know that they existed, and we're still sifting through photo albums to see if we can find a picture of the shadow box.

"I do know that they made it to Canada, and they were passed on down to the youngest boy, which would have been Harry's youngest nephew."

While William went on to have five children, one of whom was called Harry, sister Alice died of tuberculosis.

Sister Bessie had a daughter of her own in Bristol.

Harry Dunn's great nephew George Dunn and cousin Beth Vanderhelm at William Dunn's grave in Ontario

Now that the branches of the Dunn family have been reunited, they both have a renewed interest in finding out what happened in the past.

Mr Keepin said: "Both sides of the family have totally got the bug now.

"It's a bit of a jigsaw which we're still trying to work out but we're beginning to put the pieces together."

Ms Vanderhelm and George Dunn hope to visit the UK in the next two years, and a trip to Harry Dunn's grave is at the top of their list.

'Family has re-connected'

Simon Bendry from the CWGC said that every year, the commission makes numerous requests to find relatives but rarely makes contact.

He said: "What has been remarkable about this case, is how so many members of the family have connected with the story, not only in the local area, but further afield and even as far away as Canada.

"A family has re-connected with a long-forgotten relative and he is now remembered by them.

"It is a reminder of the importance of the work of the CWGC, to ensure those who served and died are appropriately commemorated and an example of how our work continues to connect families with those who died in the world wars."

What the family hope to find next is a picture of Harry Dunn or his medals and they are urging anyone who may have these to get in touch.

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published1 February 2024

- Published6 November 2023

- Published27 September 2023