Cambridge's Fitzwilliam Museum explores artist-mannequin relationship

- Published

Mannequins have been a mainstay of the artist's arsenal for centuries.

The relationship between artist and mannequin dates back hundreds of years. Now an exhibition at Cambridge's Fitzwilliam Museum has revealed how that relationship was not always strictly professional.

Few art students will have have escaped the clutches of the diminutive wooden mannequin. They have been a mainstay of the artist's arsenal since at least the Renaissance.

A three-month exhibition starting in October aims to demonstrate how they have gone from being an "inconspicuous studio tool, a piece of equipment as necessary as easel, pigments and brushes" to being "the fetishised subject of the artist's painting" and - in the 20th Century - "a work of art in its own right".

"The articulated human figure made of wax or wood has been a common tool in artistic practice since the 16th Century," says Jane Munro, curator of the exhibition.

"Its mobile limbs enable the artist to study anatomical proportion, fix a pose at will, and perfect the depiction of drapery and clothing.

"From the Renaissance onwards mannequins were used by artists and sculptors to study perspective, arrange compositions, 'rehearse' the fall of light and shade and, especially, to paint drapery and clothing.

"Over the course of the 19th Century the mannequin gradually emerged from the studio to become the artist's subject, at first humorously, then in more complicated ways, playing on the unnerving psychological presence of a figure that was realistic, yet unreal. Lifelike, yet lifeless."

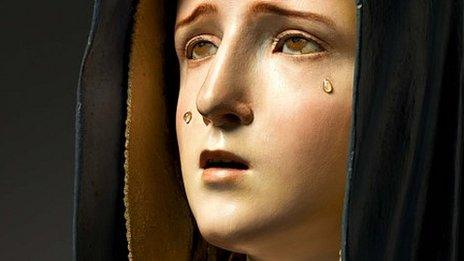

Mannequins came in a variety of forms and could be "eerily realistic with articulated skeletons and padded exteriors"

"The world of the mannequin was strange, surprising and riddled with contradictions," she adds. "Artists at once recommended them and warned of the dangers of their over-use.

"In 19th Century Paris, the centre of the mannequin-making industry, extraordinary levels of inventiveness were devoted to making and 'perfecting' the life-size mannequin, with the aim of making it an ever-closer approximation of 'the human machine'.

"Available as female and children, these figures were eerily realistic with articulated skeletons and padded exteriors, designed to have increasingly fluid movements only to be keyed into position to retain a pose.

"Paradoxically, even 'realist' painters like Gustave Courbet and the Pre-Raphaelites used these artificial figures to make their paintings 'truer' to nature."

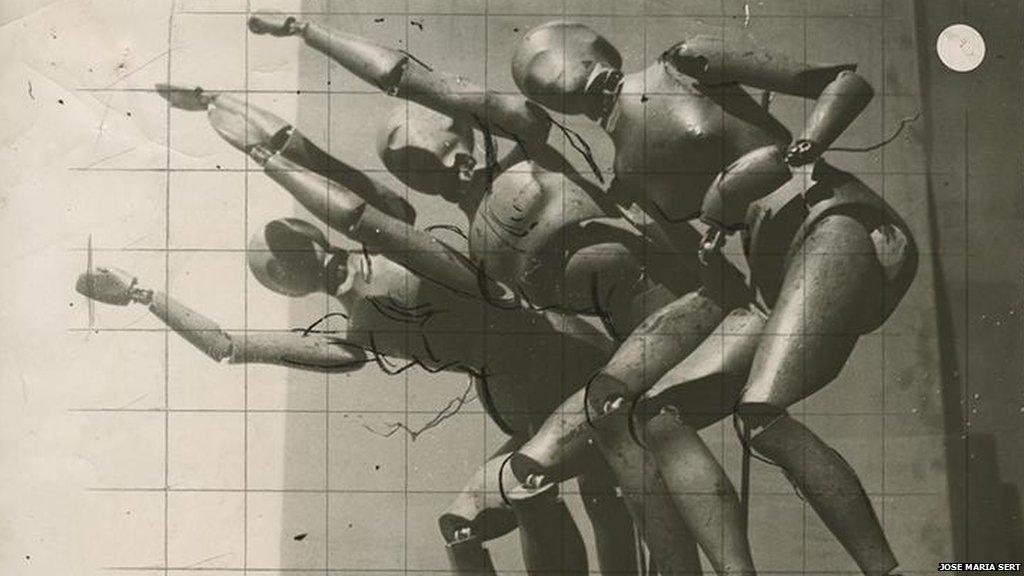

In 1937, José María Sert did this photographic study for The Triumphs of Humanity

Ms Munro tells how sometimes the relationship between artist and mannequin could take a "shocking" turn. One of the "more bizarre" accounts involves the Austrian artist Oskar Kokoschka.

He had a custom made "love doll" made in the image of his former lover Alma Mahler. He fell in love with her in 1912 but their relationship ended two years later after Alma fell pregnant and had an abortion.

Kokoshka was badly wounded in 1915 during World War One while serving on the front line.

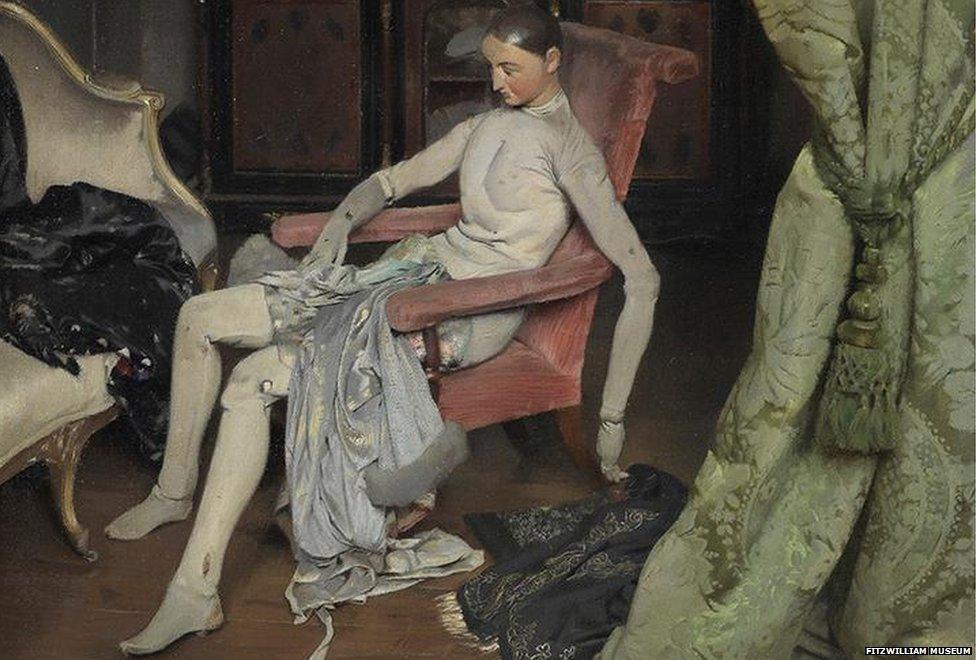

This oil on canvas painting called, simply, 'Reposing', by Alan Beeton features a lay model

On his return from the war, he found Alma had remarried.

To console himself he commissioned a life-sized doll, closely modelled on Alma, from the avant-garde doll-maker Hermine Moos.

A sexual substitute or fetish, the doll featured in a number of his paintings. It was, says Ms Munro, "an object of erotic longing he generated first to worship, then to eliminate."

The doll was eventually beheaded at a party and had a bottle of red wine broken over the body.

In a letter to Moos, Kokoschka wrote: "Finally, after I had drawn it and painted it over and over again, I decided to do away with it. It had managed to cure me completely of my Passion."

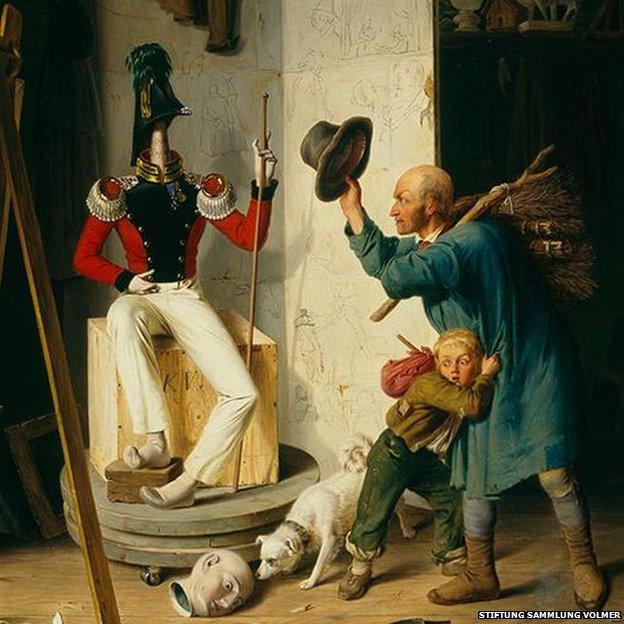

A mannequin in action in Heinrich von Rustige's painting The Farmer in the Artist's Studio (c 1839)

British painter Alan Beeton had a far less intense relationship with his mannequin, which crossed the boundary from prop to subject in a number of his works between 1929 and 1931.

A group of his mannequin still life paintings will be highlights of the Fitzwilliam's 'Silent Partners' exhibition in October. As will the original mannequin - tracked down to a workshop of one of Beeton's descendants.

"It took years of research, a modicum of detective work and a series of happy coincidences to track it down," Ms Munro said.

"Its nose was broken and crudely repaired by a well-meaning amateur sculptress, and its hands and fingers torn and tattered from age, use and abuse.

"For all that, it exuded a warm, benign expression and seemed as relaxed and nonchalant as it appears in many of Beeton's paintings."

Restored with the help of three specialists, it will be one of more than 180 exhibits drawn from across the world for the exhibition.

- Published31 July 2014

- Published30 July 2012