WW1 Wimblington soldier's return from the dead

- Published

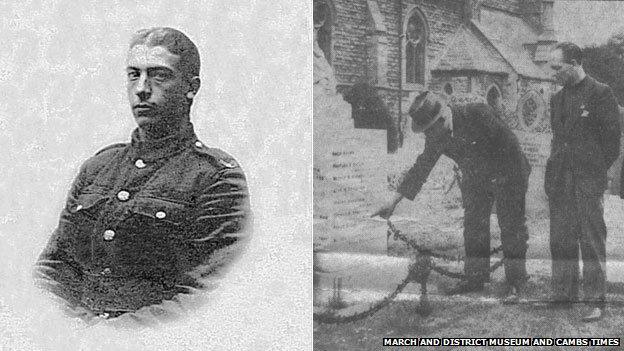

Percy in 1915 and with his brother Fred in the 1940s, pointing to his name on the Wimblington memorial

It was a tale of deception, double lives, attempted murder and, ultimately, suicide, which finally unravelled after a cleaner exposed a lie. But why did English World War One soldier Percy Bush Cox want to live as Australian Ernest Durham?

Percy Cox was born in Wimblington, Cambridgeshire and was a farm worker until World War One, when he enlisted in the Royal Leicestershire Regiment.

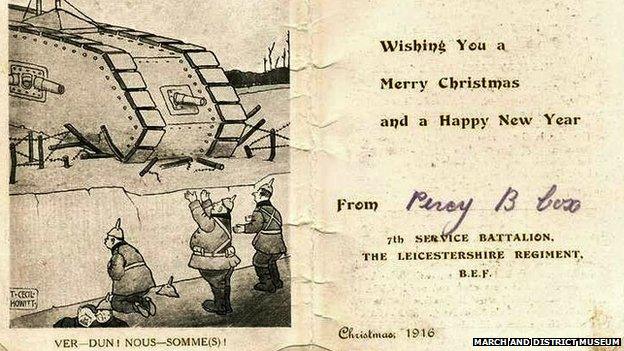

By 1916, he was sending postcards to a friend after being pitched into battle on the Western Front.

At some point during the conflict, the private hatched a plan with three other British soldiers to swap identities with Australians.

He appears to have been motivated by money, because Australian soldiers took home eight times as much as the British Tommies' wage of one shilling a week.

When he crawled past the body of Ernest Durham in 1918, he saw his opportunity, according to an historian.

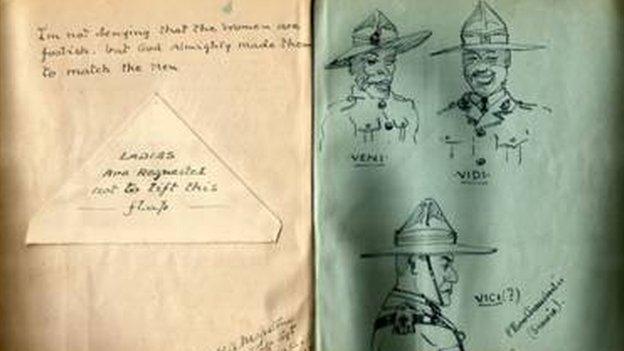

Percy sent this Christmas card to a friend from the Western Front in 1916

Amanda Carlin, chairwoman of March and District Museum, has studied Percy's life.

She said: "He and the three British soldiers crawled across No Man's Land to four dead Australians and changed their uniforms, took their dog tags."

Percy's earning potential had rocketed, because "while Australians earned 8 shillings a week, we know that Ernest Durham was earning 11 shillings a week", she added.

It was not, though, an attempt to desert.

After spending time in a field hospital with what is thought to have been an arm injury, Percy went on to see action in the Australian army.

According to Mrs Carlin, he would not have stood out because of Australia's "Anglo-only immigration policy", which meant many of the Australians had British accents. He and his comrades were also fortunate enough to be sent to a different platoon.

Meanwhile, the Cox family were told Percy was missing in action and in 1919 informed he was presumed dead. It was not long before Percy Cox's name was added to Wimblington's war memorial.

It seemed Percy had got away with the deception, but leaving the army following the war was the first step towards his life starting to unravel.

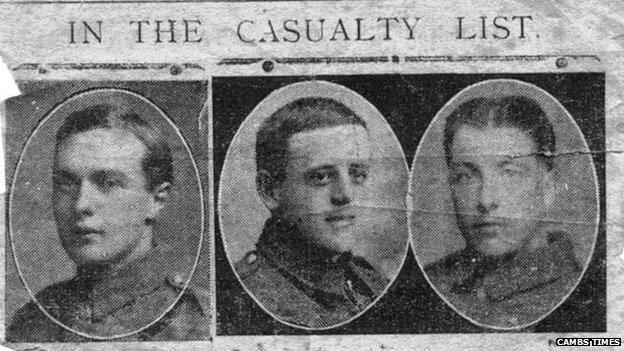

The farm worker enlisted in the Royal Leicestershire Regiment and went missing in 1918

On being demobbed Percy emigrated to Australia, but in 1925 he returned to the UK, still calling himself Ernest Durham, and set up home in Sawston in south Cambridgeshire.

It would be another 15 years before he decided to reveal to his family that he was actually still alive.

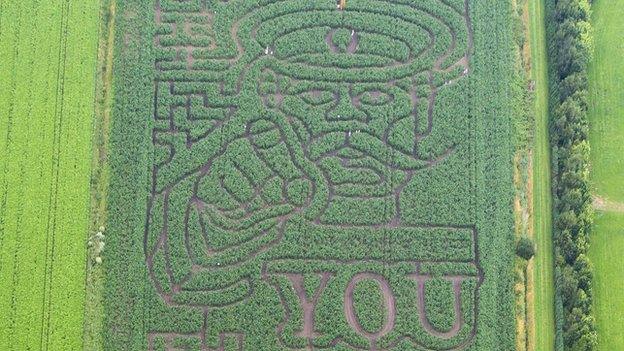

The move led to a photograph being published in a newspaper in the 1940s, where Percy can be seen standing beside his brother Fred and pointing to his name on the Wimblington war memorial.

Despite this, he continued to live as Ernest Durham in Sawston until 1952 when he employed a cleaner, Dorothy Piper.

Mrs Carlin said: "Mrs Piper found the newspaper cutting where Percy was pointing out his name and she realised he was living out this double life, so she and her husband began to blackmail him."

After he died, a letter written by Percy was found in which he said: "I can take no more of this blackmailing by the Pipers.

"They have had to the tune of £400 out of me in the last nine months, a new bedroom suite, a TV, radio and washer."

On 30 December 1952, when Mrs Piper turned up for work, he took up a gun and chased her out of the house, shooting at her.

Mrs Carlin said: "She ran outside and he ran after her... she was screaming and screaming.

"He shot her again and then turned the gun on himself."

Dorothy survived and while she was never convicted of blackmail, Mrs Carlin said she believes the Pipers received about £2,000 from Percy.

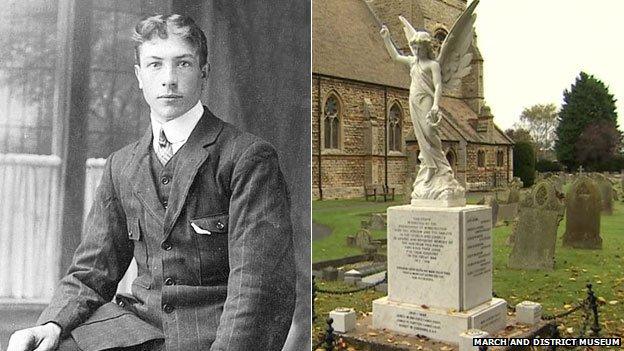

Percy before the war in 1910 and the war memorial at St Peter's church, Wimblington, now without his name

The full story of his deception finally went public, but it was not until 2005 that Percy Cox's name was removed from Wimblington's War Memorial.

Brian Krill, the Cambridgeshire representative of the War Memorials Trust, advised the parish council to remove the name.

He said: "Thinking of all the other names on there, I'm sorry, I have no sympathy at all for Percy."

But for Mrs Carlin, having read the inquest into his death and hearing about his mood swings, Percy "was a victim of war".

"It appears from accounts that he may have lost his mind, he might have been shell-shocked - we understand these things so much better now," she said.

- Published22 July 2014

- Published18 July 2014

- Published23 January 2011