Ozone layer hole: How its discovery changed our lives

- Published

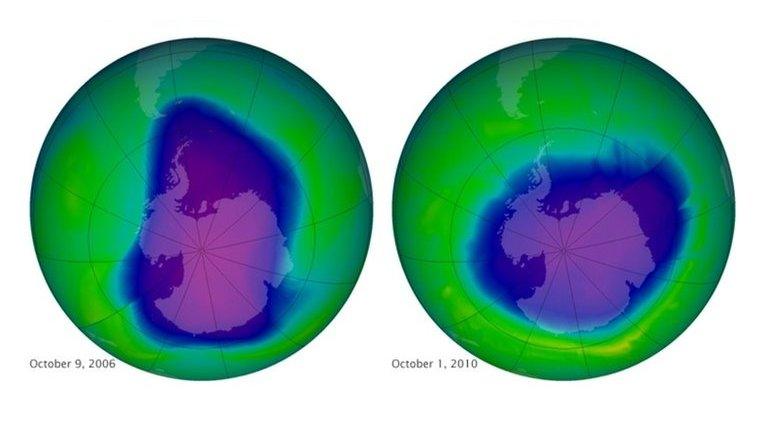

The largest hole in the ozone layer appears over Antarctica

Thirty years ago three scientists from Cambridge found a hole in the ozone layer, a shield high in the sky protecting us from potentially lethal solar radiation. It changed the way we live in several important ways, ranging from international relations to beauty products.

Jonathan Shanklin, together with Brian Gardiner and the late Joe Farman, was part of the British Antarctic Survey team which discovered the hole in the ozone layer in 1985.

"I suppose I have changed the world," he says, citing one of the greatest legacies of his discoveries as "how fragile our environment is and that we tamper with it at our peril".

The response to this peril was bold, decisive and occasionally surprising.

War paint and rickets

The Australians were ahead of the pack when it came to sun protection. Australian cricketer Shane Warne even wore zinc oxide sun block in Manchester in 1993

Before 1985, most people saw the primary aim of a holiday abroad as being to return to the UK with your skin roasted. Some people even purchased special tanning lotions to intensify the sun's rays.

For many men, in particular, using sun protection creams was a peculiar and messy business - and not very masculine.

The ozone hole changed all that, says Prof Charlotte Proby, of the British Association of Dermatologists.

"Australia were significantly ahead of us," she says. "They got people to sign up to it.

What is the ozone layer?

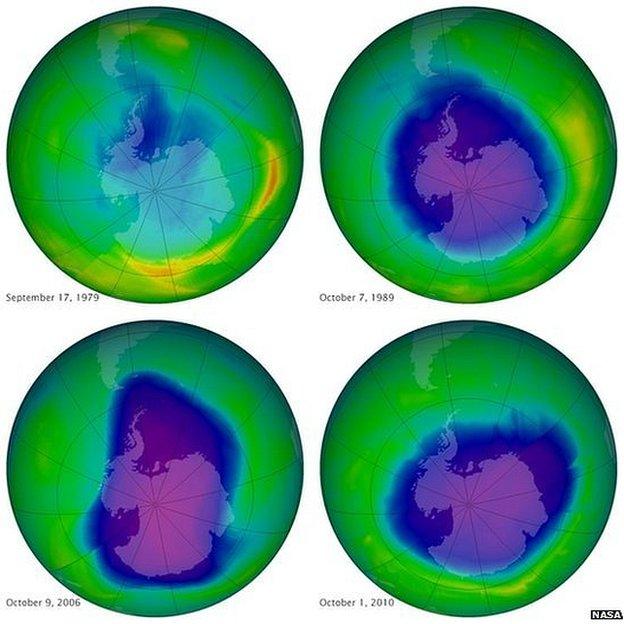

The purple areas show how the ozone layer has depleted over time

Ozone O3 is an 'allotrope' of oxygen - a form of oxygen that is different to O2, the gas that makes up 21 per cent of the atmosphere. Ozone is formed from oxygen in a reversible reaction.

The ozone layer is the part of the upper atmosphere where ozone is found in the highest concentrations.

The ozone there absorbs ultraviolet radiation, preventing most of it from reaching the ground. This is important because ultraviolet radiation can lead to skin cancer.

"Antipodean cricketing, rugby and tennis stars were suddenly turning up at Lord's, Twickenham and Wimbledon wearing what appeared to be battle paint.

It was, of course, zinc oxide sun block. Such sights, says Prof Proby, helped normalise sun protection cream use in the UK.

Yet the message about sun cream use may, she warns, have been too simplistic. The right amount of sun protection depends on skin type - the darker the skin, the less protection is needed.

"Yes, people embraced sun screen. But the pendulum has swung the other way and now the levels of sunlight some people get are not enough," says Prof Scott. "We're now seeing cases of Vitamin D deficiency and rickets, external."

Spray tans

Would spray tans exist if the ozone hole had not been discovered? Possibly not, according to one skin expert

Would spray tans have taken off had the hole in the ozone layer not been discovered?

Possibly not, says Prof Proby.

Today's widespread use of spray tans emerged, she says, from a growing awareness that "the sun ages skin".

Although fake tanning products were available before 1985 - some people used to use tea bags to stain the skin - the boom for the spray tan industry has been in the past 20 years.

"I fully advocate them," says Prof Proby, "though people need to remember that they give you no protection from the sun."

New slogans

The discovery of the hole in the ozone layer led to the use of alternatives to chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in products such as hair spray

If the Cambridge scientists who discovered the ozone hole were the heroes of the story, the "baddies" were definitely the aerosols and refrigerators blamed for causing it.

These contained chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) which had eaten through the ozone layer. They were quickly outlawed across the globe once the ozone layer hole was discovered.

Shop shelves were suddenly deluged with new advertising slogans, such as "ozone friendly", "environmentally friendly" and "CFC free".

Manufacturers, who may have felt threatened by the ban on CFCs, instead embraced the ozone hole and used it to their advantage to sell goods which used alternative compounds, says climate scientist Professor David Vaughan.

And people bought them, says Prof Vaughan, because to do so made people feel like they had done something beneficial, without actually having to change their behaviour.

"We still have aerosols, they just don't use CFCs," he adds.

"The development of alternatives to CFCs had started before the discovery of the ozone layer hole. The shift to these alternatives worked so well because the commercial willingness was there."

Countries working together

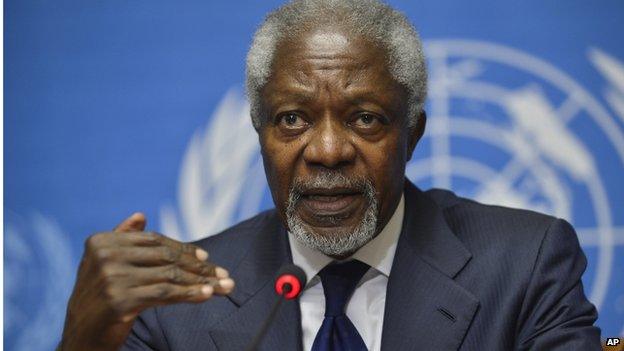

Perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date: Kofi Annan's verdict on the Montreal Protocol

The discovery of the hole in the ozone layer showed what was possible when the nations of the world came together with a shared goal - in this case, saving the planet.

Two years after the hole's discovery, an international agreement had been struck to protect the ozone layer.

What made the Montreal Protocol even more exceptional was the speed with which it was agreed - something Prof Jane Francis, director of the British Antarctic Survey, says was "really amazing".

The deal, signed in 1987 by 46 states, went on to become the first United Nations treaty to achieve universal ratification., external

By 2010, the parties to the protocol had phased out the consumption of 98% of all of the chemicals controlled under the agreement.

Kofi Annan, former Secretary General of the United Nations, said Montreal was "perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date".

Politics

The hole in the ozone layer helped put the environment centre stage in mainstream politics

"One of the most amazing things about the discovery of the ozone hole" was the way it propelled environmental issues on to the centre stage of politics, says Prof Jane Francis, director of the British Antarctic Survey.

Not that environmental concerns were new. Far from it.

Before the ozone hole, environmental issues such as the London smog of the 1950s or the use of the toxic insecticide DDT in the 1970s emerged, were dealt with and then disappeared.

But until 1985, environmental issues in politics were like tennis balls bounced against a wall. The hole in the ozone layer changed all of this. The tennis ball got lodged in the wall, turning "the environment" into a constant political issue.

This year, the main political parties all offered up environmental pledges, including tree planting, prioritising support for organic farms, promoting renewable energy and investing in zero emissions vehicles.

The new Conservative government - whose 2010 slogan was "Vote blue, Go green" - promises it will lead the "first generation to leave the natural environment of England in a better state than that in which we found it".

A bit of a change from their 1983 manifesto, which described "environment" as "a clumsy word for many of the things that make life worth living".

- Published11 September 2014

- Published14 May 2013