Pevensey giant whale remembered 150 years on

- Published

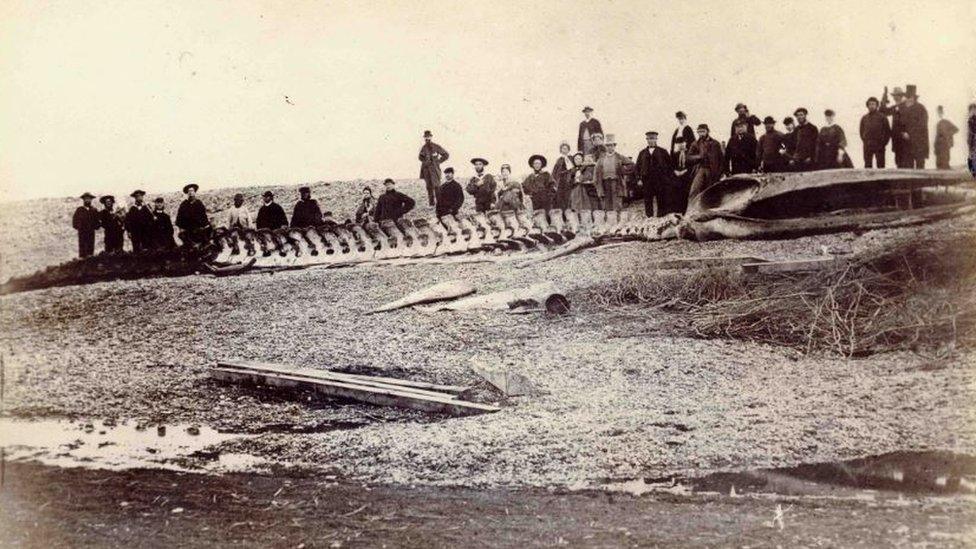

When a giant whale was washed up on a beach in Sussex, 40,000 people travelled by train to take a look.

Exactly 150 years on, plans are well under way for it to become the centrepiece of a new museum building.

The 70ft (21m) finback whale was discovered at Pevensey Bay on 13 November 1865.

Photographs show people posing beside its corpse.

Updates on this story and more from Cambridgeshire

Tracy Biram, of Cambridge University's Museum of Zoology, said it was "a massive deal at the time" - for most people it would have been the first time they had seen a whale.

It was also a huge specimen - the finback is the second largest species after the blue whale.

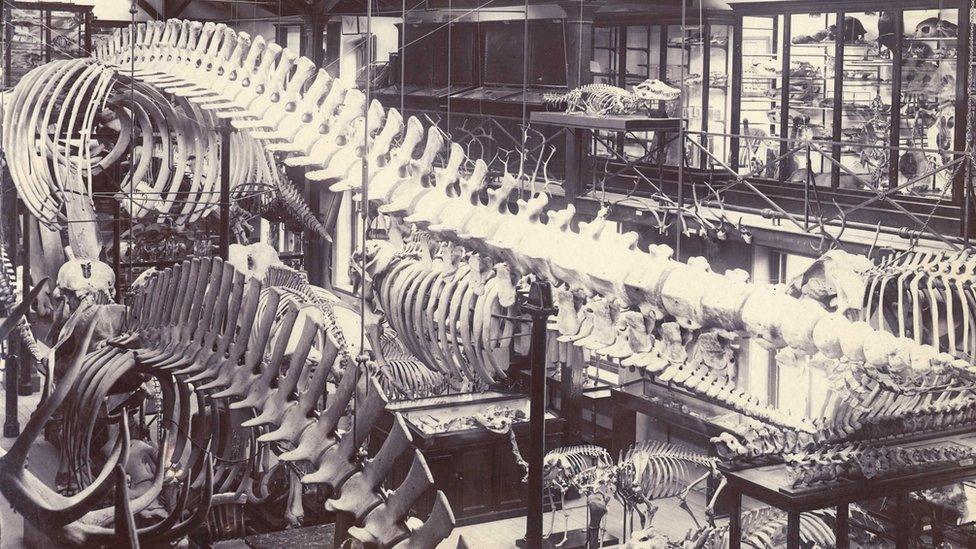

It is believed to be the biggest Finback whale skeleton on display and was bought in 1866 by John Willis Clark, the museum's superintendent

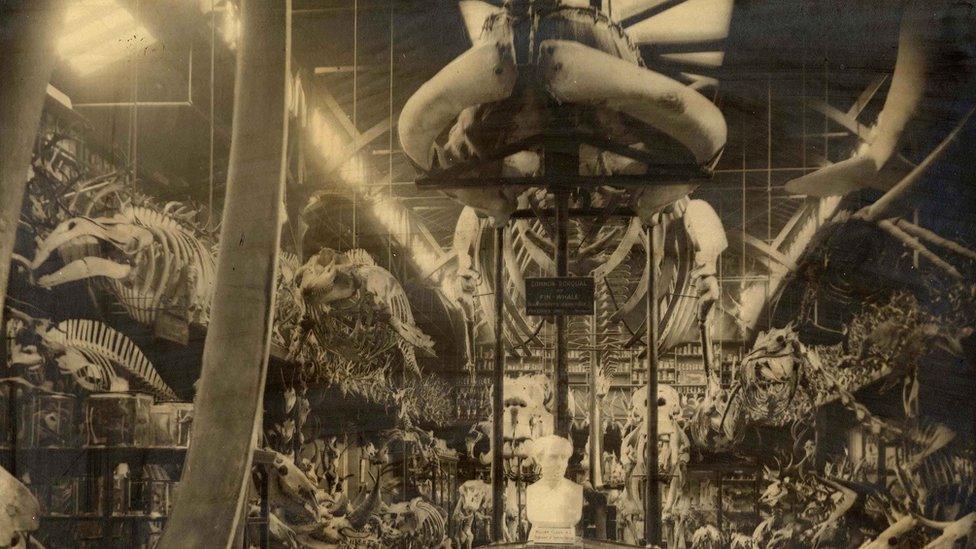

The whale had been on display at Cambridge University's old Zoology Museum in 1896

The skeleton was sold to Cambridge University for £80 the following year (nearly £9,000 at today's prices), but it was many years before it was next seen in public.

Ms Biram said: "It took a very small team 30 years of engineering and lab work to clean it, conserve it and create the structure to mount it."

When it was finally put in place in 1896, the Museum of Zoology was open to the public by appointment only, as it was a teaching resource for students and academics.

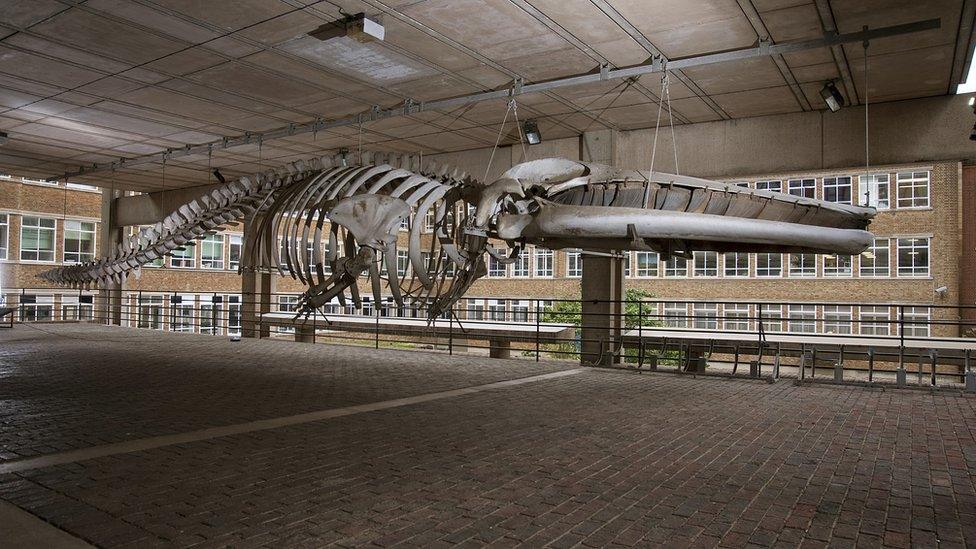

Since 1996, it has been hung outside the 1960s museum which replaced the Victorian structure.

Ms Biram said: "It's seen as odd and misguided to put it outside in the elements today, but it hadn't been damaged, it was just very dirty, and we discovered a pigeon skeleton hidden inside when we dismantled it as part of the museum's redevelopment."

The finback whales are also known as fin whales. This young female was washed ashore in Kent in October

The mammals are still a rare enough sight to attract attention, even in the age of wildlife documentaries and whale-watching tours, and even when dead.

"It's not a morbid fascination," said Ben Garrod, an Anglia Ruskin University evolutionary biologist.

"It's the closest thing many of us have to a wild experience and, rightly or wrongly, when they strand that's our rare opportunity to see them."

The fascination with beached whales appears to have been with us for centuries.

In early 17th Century Netherlands, crowds flocked to see sperm whales washed ashore by storms along the North Sea coast, according to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

A stranded whale was discovered underneath layers of paint during the conservation of one of its 17th Century Dutch, external paintings last year.

The whale was painted out before the picture was given to the Fitzwilliam in 1873

It was one of many images of whales and other "aquatic wonders" printed at the time, and the museum believes the whale was painted over in the 18th or 19th Century to suit changing tastes or to make it more marketable.

However, for people of the 17th Century the mammals were seen as sea monsters or signs of impending disaster.

Mr Garrod said: "We now know they're not killers, but then they were the unknown monsters, or the biblical Leviathan.

"And in the 19th Century, the novel Moby Dick shaped generations of people's views of whales, the way the film Jaws shaped our idea of Great Whites."

The Pevensey Bay whale was still drawing crowds when it was a skeleton

About 5% of the 600 cetaceans found stranded around the UK coast every year are whales, according to Rob Deaville.

He is the project manager of the Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme, which investigates whale, dolphin and porpoise strandings on behalf of Defra.

They are far more likely to be the smaller whale species such as the minke than the finback, although several of the latter have been discovered this year.

Scientists still have so much more to find out about whales.

Mr Deaville said research carried out by the Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme, including post-mortems to uncover cause of deaths, "allows us to learn more about marine species that are otherwise very difficult to study".

"Seventy percent of the world is covered in water and we don't know what's down there," said Mr Garrod.

"Just a week ago we got the first-ever footage of a brand new species of whale, the Omura's whale."

The museum rebuild received £1.8m from the Heritage Lottery Fund and is part of a bigger site redevelopment

The Pevensey Bay skeleton was dismantled last year, because the Museum of Zoology closed for a substantial £3.67m rebuild.

Museum staff have raised nearly half the £150,000 they need to conserve, external it and their other large skeletons.

It should be back on display, in pride of place in its own glass hall, early in 2017.

- Published27 October 2015

- Published14 October 2015

- Published6 October 2015

- Published21 March 2014

- Published23 September 2013

- Published4 June 2013

- Published8 March 2012