Viscount Fitzwilliam and the French ballerina: A forgotten love story

- Published

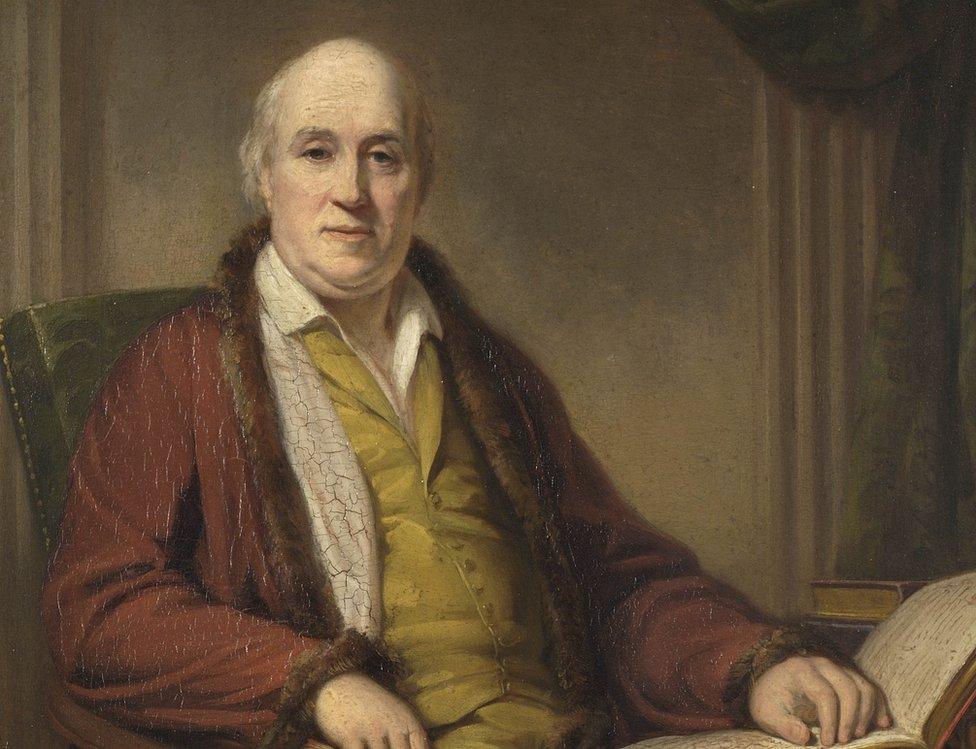

Richard Fitzwilliam died on 4 February 1816, leaving 144 paintings, 10,000 books, albums of Old Master drawings, medieval manuscripts and musical scores to Cambridge University

The forgotten story of the Fitzwilliam Museum founder's love for a Paris dancer has been revealed 200 years after the aristocrat's death.

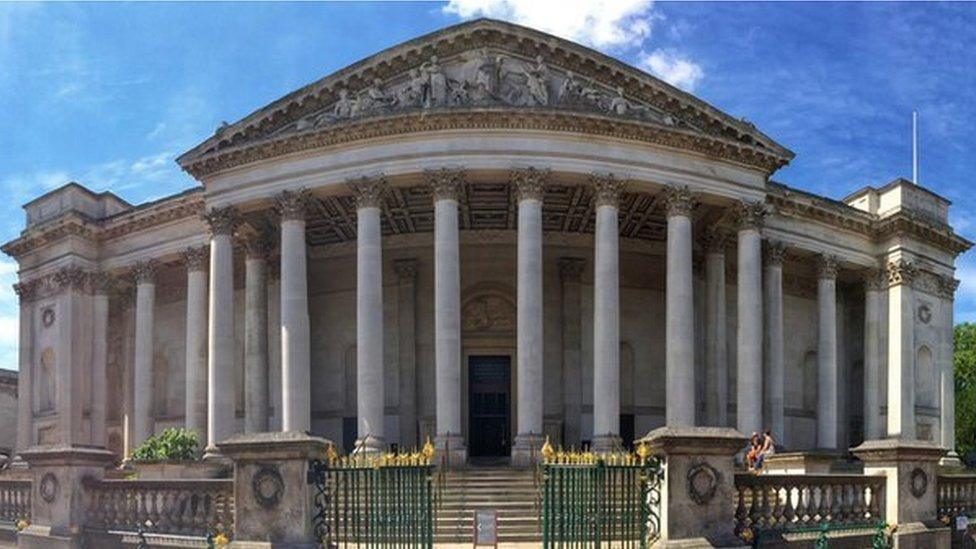

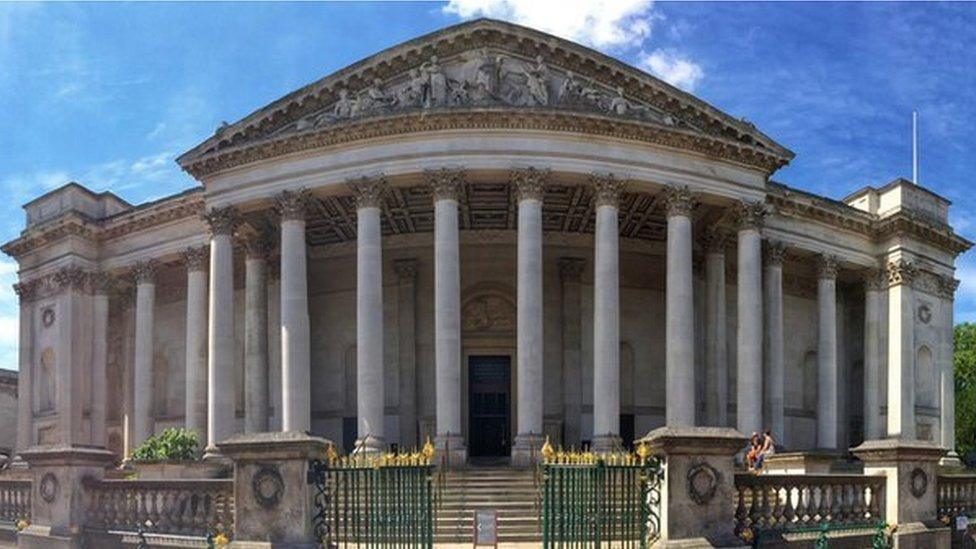

When Richard, 7th Viscount Fitzwilliam left his art collection, books and manuscripts to Cambridge University in 1816, it became the nucleus of the "finest small museum in Europe", external.

Yet, while his name lives on through the museum he founded, the story of his six-year-long affair with a teenage Paris Opéra dancer was entirely forgotten until the late 1980s.

It came to light when a cache of 299 letters from the dancer to her lover were uncovered in the Pembroke family archives at Wilton House in Wiltshire.

A print of a painting by Louis Marie Sicard, dated 1789, is thought to be a caricature of Lord Fitzwilliam in the guise of the clown Pierrot, and Zacharie. The caption translates as: "Oh! What a mouthful!"

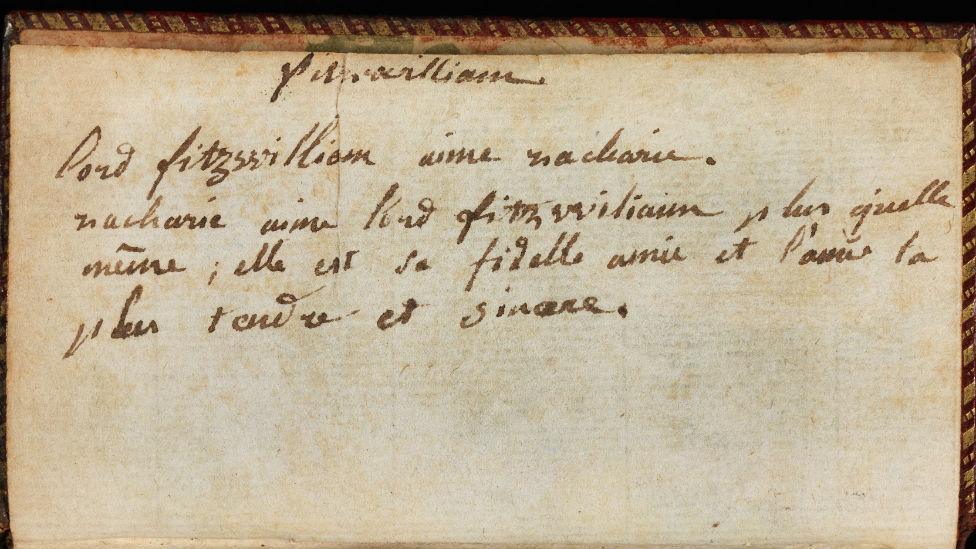

She used the stage name Zacharie - a name which more than one Fitzwilliam Museum curator had spotted inscribed in a book in the collection.

The Fitzwilliam's keeper of antiquities, Lucilla Burn, said: "But until the letters appeared which detailed the course of the affair over six years, we didn't know who this Zacharie was."

The story of the affair is published for the first time in The Fitzwilliam: A History, written by Dr Burn to mark the museum's bicentenary year.

He also left the university £200,000 to house the collection - and the current building on Trumpington Road, Cambridge opened in 1848

Richard Fitzwilliam, who was born in 1745, inherited estates in Ireland from his father, the sixth viscount, and wealth and a love of the arts from his mother, Catherine Decker.

After he graduated from Cambridge University his musical interests drew him to France, where he studied the harpsichord in Paris - "the cultural Mecca of the civilised world".

Dr Burn said: "Besides the Opéra, the theatre and the great collections of paintings and sculpture... there was also a lively and sophisticated social scene."

This inscription describes Zacharie's love for Fitzwilliam and is found in an almanac in the museum's collection

Zacharie - who was born Marie Anne Bernard - was a 15-year-old dancer when she met the Irish peer in 1784.

She had an older cousin, Marie-Madeleine Guimard, a star ballerina whose salon attracted visiting British aristocrats.

Dr Burn said: "She obviously matured and the depth of their affection over the course of their relationship is movingly traced - but only from one side, as we have none of the letters from him to her."

The letters revealed the couple had three children - a daughter who died as an infant and two sons called Fitz and Bily.

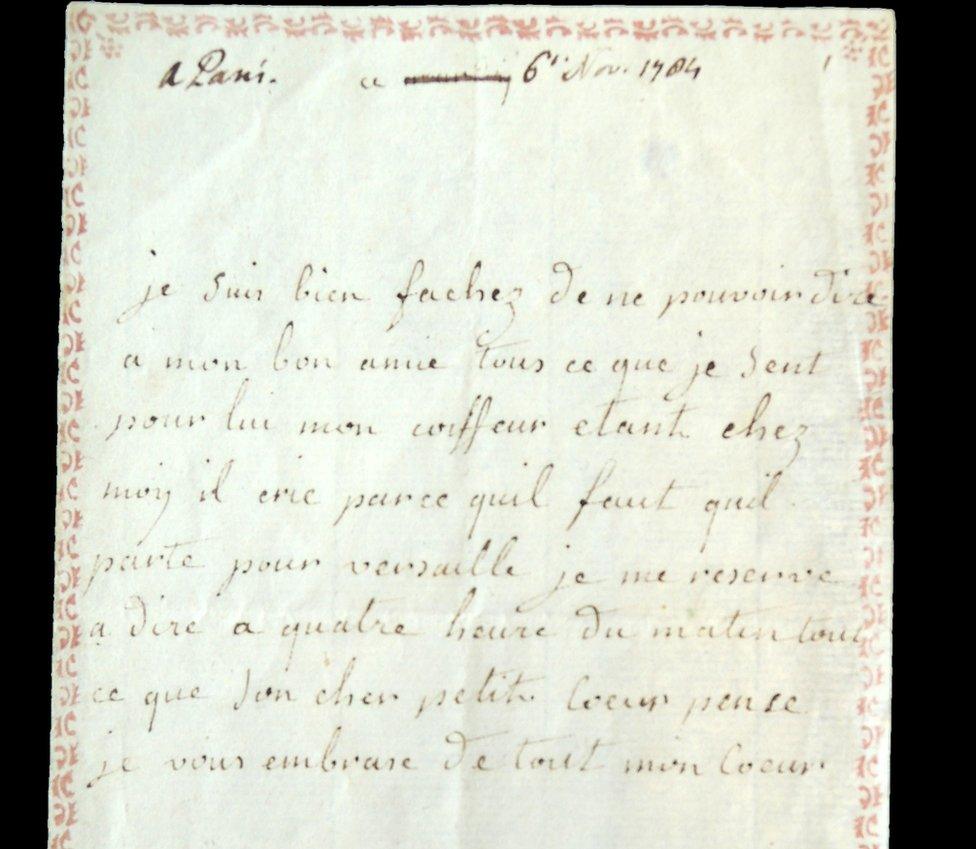

Lucilla Burn said Zacharie's early letters were "almost illiterate" - but gradually became "more sophisticated, flowing and correct"

Zacharie described Fitz cutting his teeth, learning to climb up stairs and talking about "milord Papa".

In summer 1790, she described how the boys "run about and eat all day long; and at night they sleep like little dormice".

She shares news of friends, visitors, parties and concert and opera performances.

Fitzwilliam, who was 39 when the relationship began, sent "a regular and ample supply of money".

But he continued the life of a peripatetic aristocrat, moving between his estates in Ireland, his house in Richmond and his family in Paris.

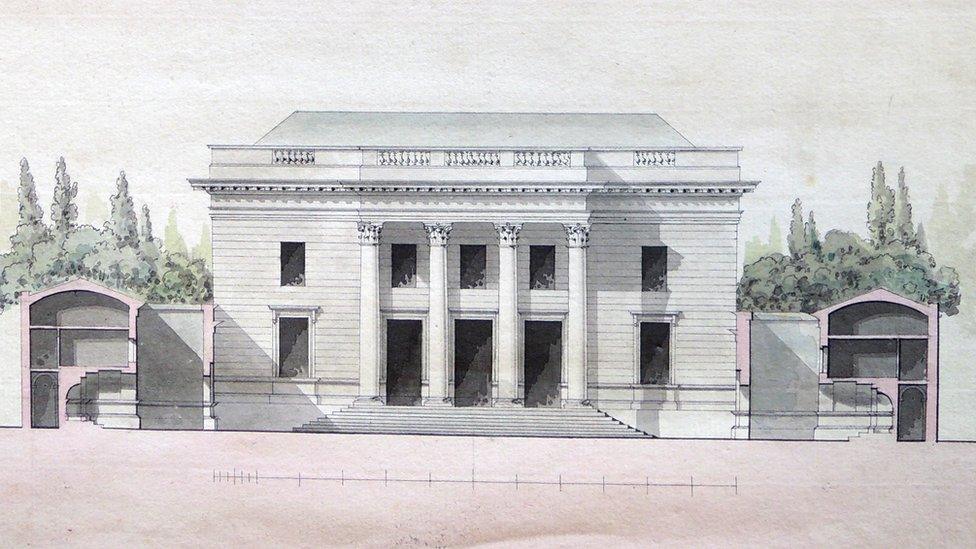

Zacharie's architect brother Pierre drew up plans for a house for the couple near Paris - but the revolution put paid to this proposal

Dr Burn said Zacharie "regularly reproached him for not visiting more often... putting off his journey and for staying so short a time".

The French Revolution began in 1789 and the young dancer appears to have had more sympathy for its aims than her aristocratic lover, who remained a staunch royalist.

Zacharie's last letter was dated December 1790, as the revolution was becoming more violent, and after that she disappears.

She was in poor health for much of that year so may have died, according to Dr Burn, or may have joined other French exiles in Richmond.

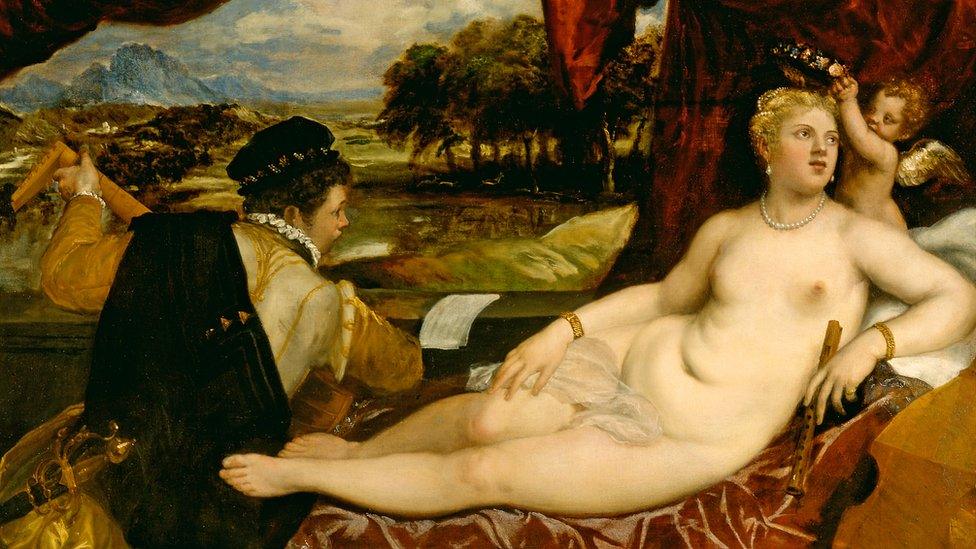

Fitzwilliam's bequest included this masterpiece by Titian, once owned by the Duc d'Orléans. The viscount probably knew it from his visits to France, years before he was able to buy it in 1798

The viscount never married and died a few months after falling from a ladder in his library and breaking his knee

Their younger son Bily has also proved impossible to trace, so probably predeceased his father.

Dr Burn said: "Happily for Fitz at least, he was living in Richmond with his wife and family at the time of Fitzwilliam's death in 1816 and they were provided for by his will."

What is known is that the viscount appears to have treasured Zacharie's letters because he still had them at his death.

They passed into the archives of his cousin the Earl of Pembroke, who inherited the bulk of his estate - and the relationship faded from memory.

- Published2 January 2016

- Published25 November 2015

- Published2 February 2015

- Published5 July 2014