Human teeth traced to fish scales, Cambridge scientists say

- Published

Origins of teeth traced back to primitive fish scales

Teeth grew from the scales of primitive shark-like fish millions of years ago, research by scientists suggests.

Old lineage cartilaginous fish like sharks, skates and rays that have skin which contained small spiky scales or "dermal denticles" may be the key, scientists say.

Cambridge University said their tooth-like appearance is no accident.

Researchers suggest it may be a direct link between us and marine ancestors from up to 400 million years ago.

During early evolution of jawed vertebrates, dermal denticles were transferred from the skins of primitive fish to their mouth.

In the millennia that followed, the tiny appendages went on to produce the flesh-tearing six-inch long teeth of dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex and the fangs of the sabre-toothed cat, the team said.

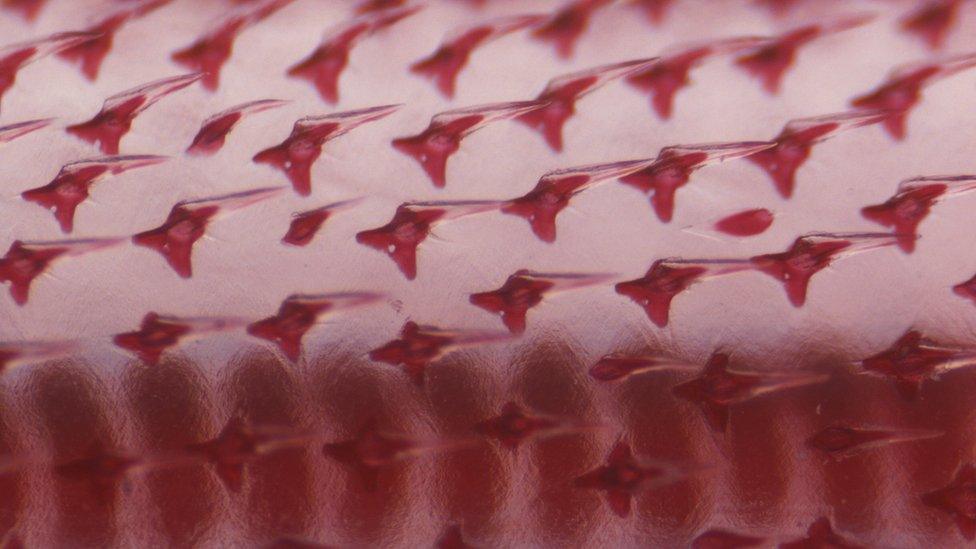

A close-up of a fish scale

Lead scientist Dr Andrew Gillis, from the Department of Zoology, said: "Stroke a shark and you'll find it feels rougher than other fish, as shark skin is covered entirely in dermal denticles.

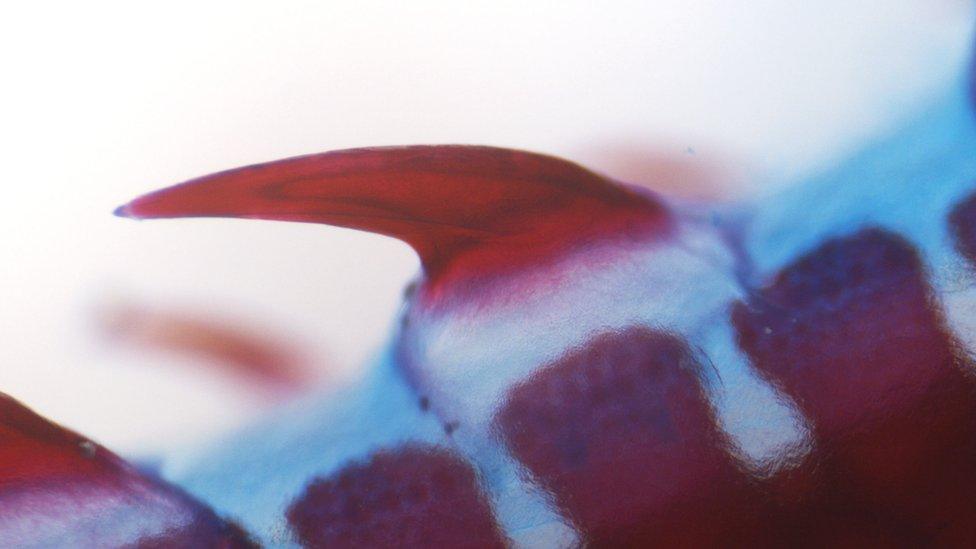

"By labelling the different types of cells in the embryos of skate, we were able to trace their fates.

"We show that... the denticle scales of sharks and skate develop from neural crest cells, just like teeth."

Neural crest cells are central to the process of tooth development in mammals said Dr Gillis, adding their finding suggest a deep evolutionary relationship between the primitive fish scales and the teeth of vertebrates.

The fact teeth and sharks' denticle scales both arise from the same kind of embryonic cell suggests a common evolutionary origin, the team reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external.

The skins of sharks are all that remains of amour plating that clad their jawless forbears some 400 million years ago to protect against predators such as sea scorpions.

- Published9 March 2016