Child bereavement: A brother's promise to help 'forgotten grievers'

- Published

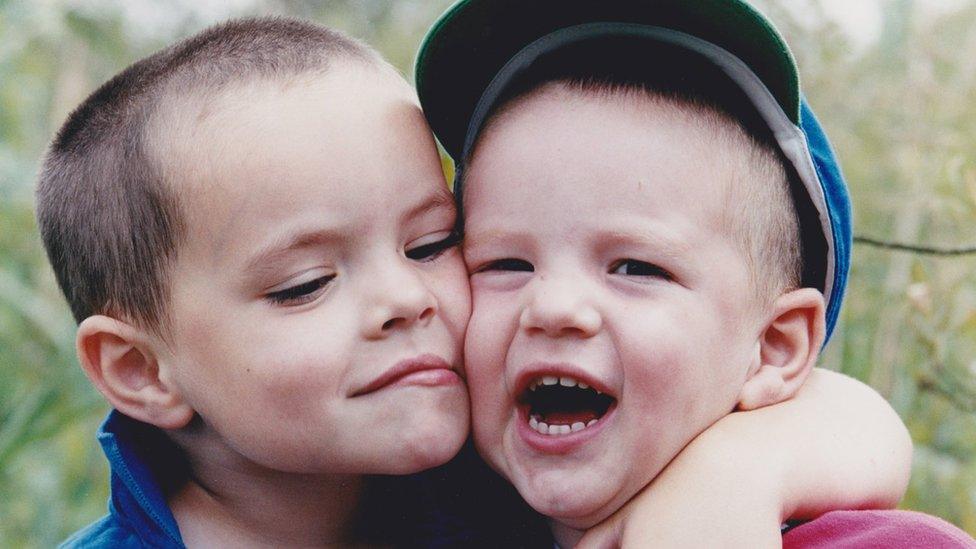

"He was the most incredible big brother; my best friend," says Callum Fairhurst (right) of Liam

When Callum Fairhurst hugged his 14-year-old brother Liam for the last time, he made him two promises: to live a great life and to help others. As the 10th anniversary of Liam's death approaches, Callum has founded a new website that aims to answer the very questions he couldn't ask as a grieving 12-year-old.

Callum Fairhurst still remembers every detail of 30 June 2009, the day his big brother Liam died.

"I was 12. I remember what I was watching on TV, what I did before, what I did after, how I was told," he says. "I didn't quite realise what was going on, when the community nurses came down I just knew. We were eating dinner at the table.

"I just knew that was the last time I'd see him. That is so vivid in my memory. The days and weeks after were more of a blur."

Liam had been diagnosed with synovial sarcoma, a rare soft tissue cancer, in July 2005, aged 10.

In the four years that followed, he refused to accept his condition was terminal, and embarked on a remarkable campaign, external, raising £340,000 during his lifetime, and a further £7m after his death.

Callum (left) said no informal support was offered to him after his brother died

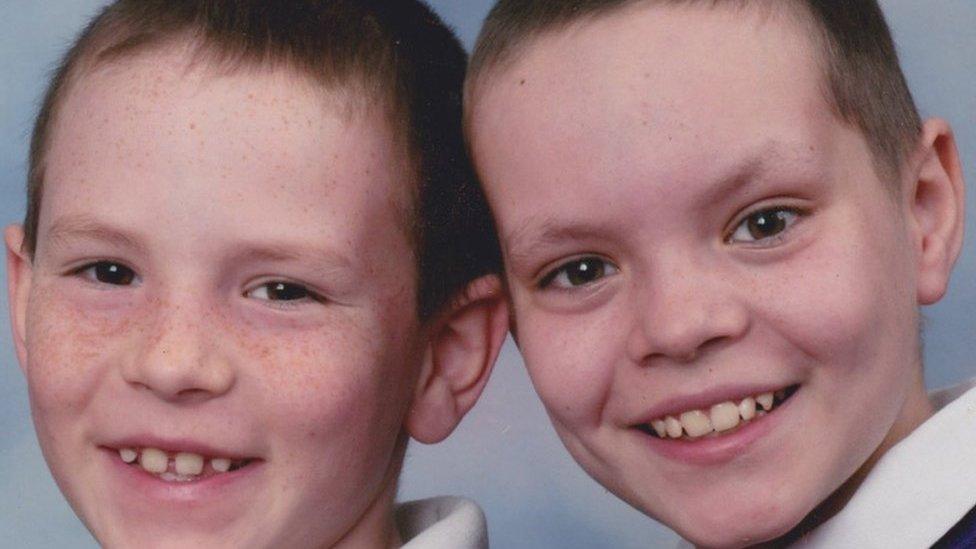

Callum Fairhurst wants to help other young people get answers in grief

Callum, from Soham, Cambridgeshire, says that in life - and death - his brother continues to inspire him, external.

"I remember kissing him and I just felt something. Although he wasn't conscious, he couldn't respond, there was something there," he said.

"Afterwards I was scared, emotional, hiding it. Looking back, I think I was protecting myself.

"People were supportive in that they'd come up and hug me. But there was no formal support. I received counselling sessions but in a way I felt forced into it, months after I needed to."

Some friends would innocently say the wrong thing, people knew him only as "Liam's brother", and the extent of direct support was a "sympathetic pat on the shoulder", he says.

"I wanted to know if it was OK to be happy. I wasn't suicidal, I wasn't depressed, but I was struggling. I had awful nightmares, but other times I was absolutely fine.

"Liam was dead, but I felt bad for getting on with it."

Liam died of cancer at the age of 14 in June 2009

Callum plunged his energy into fundraising, like his brother, cycling more than 17,000 miles (27,350km) round the world in 2015-16, and completing a tuk-tuk trip around 27 European countries last year.

He is now in the final year of an International Development and Politics degree at the University of East Anglia.

He spoke to other bereaved children to gather a cache of particular questions they had when they lost a sibling, from younger ones asking what death actually means, or 'Why are mummy and daddy being different?', to teenagers' dilemmas with drinking or drugs.

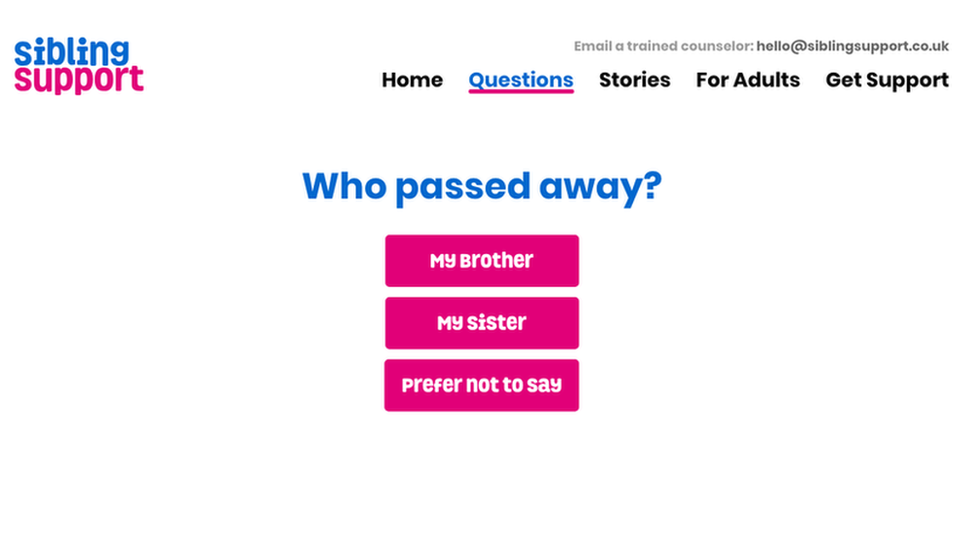

The result is a bright new online forum called Sibling Support, external, created by Callum with a pool of professionals and teenagers with first-hand experience.

It includes details of how to create memory boxes, and the plan is to install an instant message function which children can use anonymously.

You may also be interested in:

The bright and clear questions allow children and young people to get direct answers

Ann Rowland, of Child Bereavement UK, external, says children bereaved of a sibling face particular challenges.

"It can be a loss that is felt keenly at every major life event for the rest of their lives, or the realisation at an early age of the 'fragility of life'," she says.

"The child who died can be 'put on a pedestal', where only positive things are remembered, and remaining siblings can feel overlooked and that they are 'second-best'. Parents can also become overprotective of remaining children, impacting on their independence."

She says there remains a "real gap" in online support for bereaved siblings.

"This website - created by bereaved siblings for bereaved siblings - will help to decrease the sense of isolation felt by many."

Child deaths in numbers

7,653 babies, children and young people (under the age of 18) died in 2017

1 in 29 schoolchildren has lost a parent or sibling - about one child in every class

More than one in five adults in the UK know someone who lost a parent or sibling as a child

Source: YouGov for Child Bereavement UK

"The key point is informal support," Callum says.

"It could be as simple as a teacher with a five-year-old who has questions. Lots of children don't understand what death means: that she cannot eat, drink or sleep; she also can't feel any pain; she'll not wake up".

Siblings, who he describes as "the forgotten grievers", can read other personal stories, and there are animations explaining the grieving process.

Anne Streather, of Cambridge-based bereavement charity Stars, external, says young people often experience all the negative effects of grief without the mechanisms to cope.

"They can become isolated and alone, unable to concentrate at school, vulnerable to mental health issues, like self-harm and eating disorders," she says.

"Children don't understand why they feel the way they do and think no one else understands them either. They're scared."

About 180 bereaved children from across Cambridgeshire were referred to Stars last year, and in January 2019 alone referrals doubled from 20 to more than 40.

"Children often need to be reassured that their behaviour in grief is normal - that it will pass," Ms Streather adds.

"Informal support like this puts the needs of the child first."

'I was so confused when my brother died'

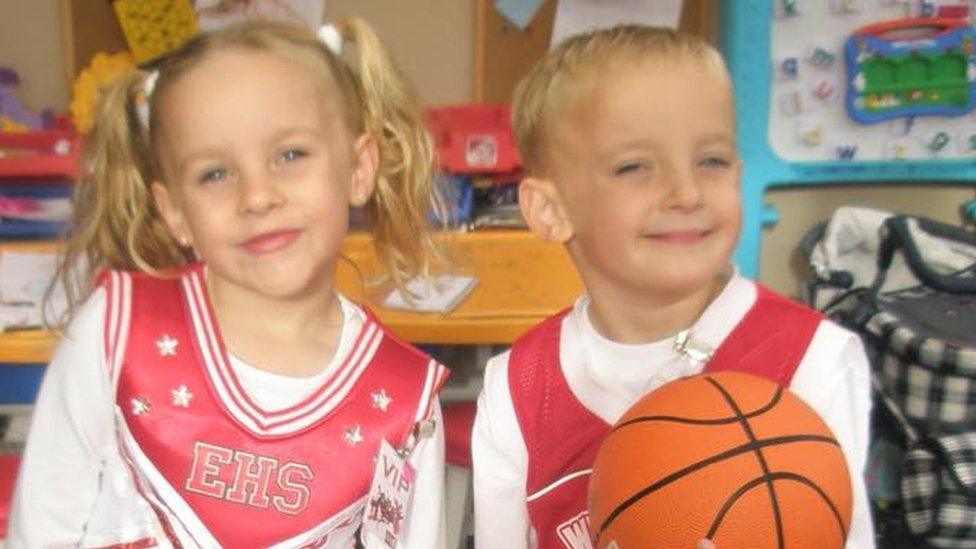

Jessica Mould, now 15, and her twin brother Harry, who died in 2009, aged five

'I still miss Harry. I'm proud of him - and I think he'd be proud of me.'

Jessica Mould, 15, from Milton Keynes, lost her twin brother Harry in 2009 at the age of five.

"I'll always remember we had a High School Musical party for our fifth birthday, and we went to the cinema and danced down the front with our friends," she says.

"It was wonderful. Every time I look through photos and videos they take me back to the moment, and that's when the feelings hit me.

"It sounds weird, but I wasn't upset when he died, just so confused. I thought he'd come back; I had no concept of death at all. Nowadays I get upset because he was so young; I wonder what he'd be like now. I still think of him as a five-year-old.

"My parents were so caring and kind afterwards. I know now they would have protected me. We went to bereavement groups but they were so far away. There was nothing local, which made it quite difficult.

"Teenagers are not very good at showing their emotions, so no matter how hard it is, share how you feel to other people - it's a relief. You will come across people who don't understand - but in the long term it's good to talk."

Callum describes bereaved siblings as 'forgotten grievers'

Callum admits that the milestones he reached, like "becoming older than Liam", going to sixth-form college and leaving home for university, hit him harder than the early days after his brother's death.

"When I'm asked 'How many brothers or sisters do you have?' - you could be on a date, you could be in a classroom - I'm not going to ignore the fact that I have a brother, or that he died.

"The 12-year-old me grieved a lot better than I did two years ago. Time doesn't heal, it just helps you deal."

- Published13 April 2019

- Published24 March 2019

- Published12 November 2018