Medieval Cambridge monks were riddled with worms, study finds

- Published

The Augustinian friars of Cambridge were twice as likely to suffer from worms than the townsfolk

Medieval monks "appear to have been riddled with parasites" despite having access to hand-washing facilities and latrine blocks, a study has found.

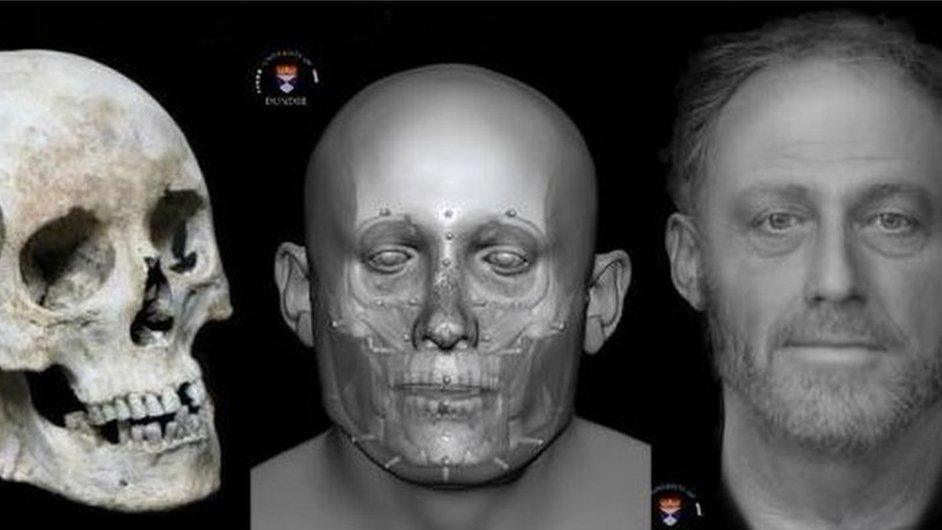

The discovery was made during an analysis of adult skeletons found in excavations in Cambridge.

It revealed the friars were twice as likely to suffer from parasitic worms than the townsfolk.

The difference may be due to monks manuring crops in friary gardens with their own faeces, the study suggests.

Most Augustinian monasteries of the period had access to latrine blocks and hand-washing facilities, unlike the houses of ordinary working people

Cambridge University, external researcher Tianyi Wang said roundworm was the most common infection, but whipworm infection was also found.

"These are both spread by poor sanitation," she added.

Sanitation in medieval towns relied on cesspits - holes in the ground used for faeces and household waste.

In contrast, monasteries commonly had running water systems, including to rinse out latrine blocks, and hand-washing facilities.

The researchers tested samples of soil around the pelvises of remains of 19 monks and 25 locals.

This showed 58% of the friars tested were infected, compared to 32% of the general townspeople.

The latter finding is in line with other studies of medieval burials - suggesting infection rates in the monastery were remarkably high.

Dr Piers Mitchell, from the university's Department of Archaeology, external, said: "One possibility is that the friars manured their vegetable gardens with human faeces - not unusual in the medieval period, and this may have led to repeated infection with the worms."

Researchers believe the infection rate could be even higher than these findings, as some traces of worm eggs would have been destroyed over time by fungi and insects

The monks were interred in the Augustinian Friary from the 1280s, while the locals were buried in the former cemetery at All Saints by the Castle church between the 12th and 14th centuries.

The town's medical practitioners were aware of the parasites.

A manuscript left to Peterhouse College by local doctor John Stockton, who died in 1361, believed the worms were generated by various forms of mucus and prescribed "bitter medicinal plants" such as aloe and wormwood to sufferers.

Dr Mitchell said this was the first time anyone had attempted to work out how common parasites were in people following different lifestyles in the same medieval town.

"The friars of medieval Cambridge appear to have been riddled with parasites," he said.

An earlier study revealed many town monks also suffered from bunions.

The research is published in the International Journal of Paleopathology, external.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published11 June 2021

- Published21 March 2017

- Published30 May 2016