Hobson's Conduit: Cambridge water course 'still relevant'

- Published

The conduit is named after Thomas Hobson - of Hobson's Choice fame - who ran livery stables in 1600s Cambridge

An ancient watercourse, known as Hobson's Conduit, has been providing a freshwater vein through the heart of Cambridge for more than 400 years. But what is it - and is it still relevant in a fast-growing city?

When the idea of the conduit through Cambridge was first dreamt up, it was a market town beset with plague, with a university built on the side of it.

The watercourse was named after Thomas Hobson, a local businessman who paid for its upkeep. It starts at the Nine Wells nature reserve near Great Shelford and travels as a brook into the city centre, breaking off into smaller channels beneath the streets.

The monument over the conduit head on Lensfield Road was moved from the Market Square in 1856. Even the railings are listed

It feeds the lake in the Cambridge University Botanic Garden and runs between Trumpington Road and Brookside to the conduit head at the bottom of Lensfield Road, which is marked with a scheduled monument. Valves - or penstocks - here control the flow of the water through the city.

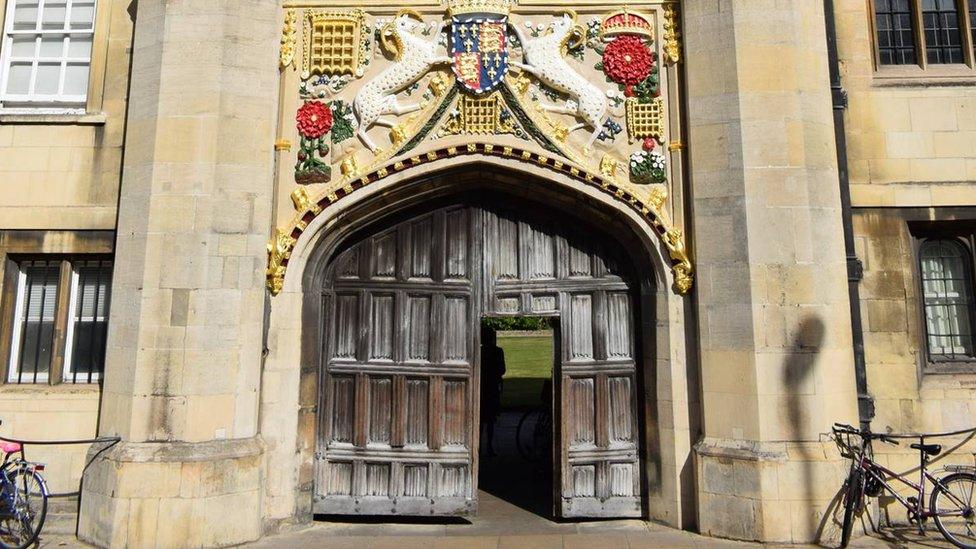

The watercourse emerges again on either side of Trumpington Street, along deep channels known as runnels, with pipes running to the water features in Emmanuel, Christ's and Pembroke Colleges.

The runnels - on the Pem side (Pembroke College) and the Pot side (Peterhouse College) of Trumpington St

It was originally completed in the early 1600s to provide clean drinking water, which could be collected in the market square.

Today, rather than providing sustenance for humans, it is a vital waterway sustaining biodiversity, external and supporting aquatic life along its route.

"It's incredibly relevant today because Cambridge is still desperately short of water and nothing has changed in 400 years," said John Latham, chairman of the Hobson's Conduit Trust, external, which looks after the waterway.

"The reason it was built was because public health was a real issue.

"By the early 1620s Cambridge's water supply was transformed by getting good clean water from Nine Wells to here. What do we still need now? Good clean water."

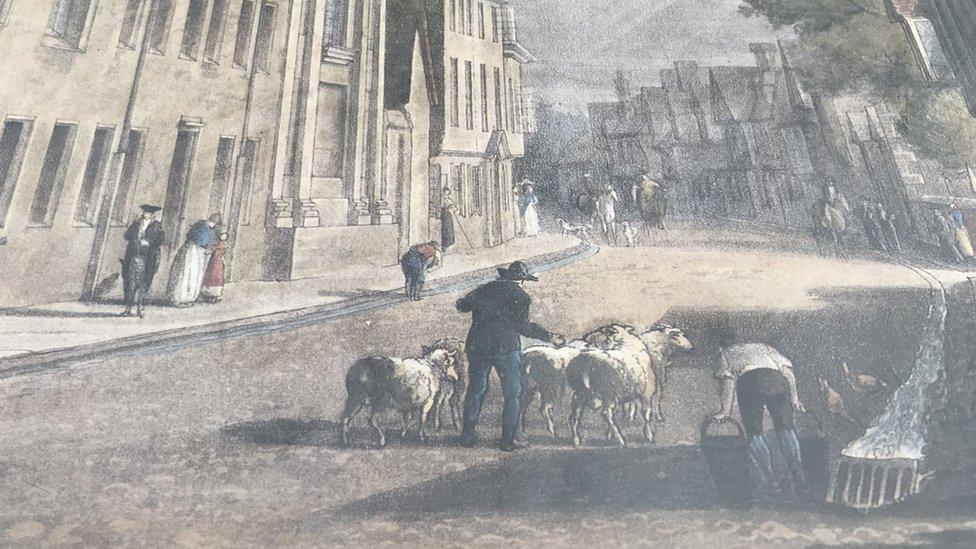

An image from 1815 shows the fully working runnels on either side of Trumpington St

Cambridge is a rapidly-expanding city, with the growth of the biomedical campus, developments at Trumpington and north-east Cambridge, and the resulting demands on the water system and transport infrastructure.

Mr Latham said: "The relentless pursuit of growth requires an adequate water supply - the Romans knew it, the Greeks knew it - but we don't - and we're supposed to be a seat of learning.

"Water is the lifegiving element that makes nature tick, whether it's plant life, bird life, invertebrates - we all need water.

"With all the pressures that exist in Cambridge this is hugely valued by residents. People feel a strong sense of proprietorial pride in it."

John Latham is chair of the Hobson's Conduit Trust, which works to protect and maintain the waterway

He said the density of new developments, although an "economic reality", meant "each square metre of green space has to work harder".

"We will have to wait another 10 years for a reservoir to be built at Chatteris which even then will not provide all the water we need," he says.

The record-breaking hot summer also caused issues with the watercourse, with the runnels having to be closed off in 2022 to prevent the levels reducing further upstream along the brook.

"We know we're getting as much rain as we ever did, and that may change of course, but it's what happens when it falls," Mr Latham says.

"This year particularly, because of the heatwave, we can't divorce it entirely from climate change.

"There are obvious consequences. Every drop we got this summer went either to feed plants or evaporated. In 2021, we'd had a lot of steady rain through the winter - but not in 2022.

"This lack of water has become a particular driver. We used to run the runnels all year round."

The weight of traffic is also affecting the structure of the runnels, with parking and access disabling and fracturing the sides. The trust hopes to eventually oversee a programme of repairs faithful to the original materials and design.

Modern traffic is damaging the structure of the Trumpington St runnels

Members of the trust also help maintain the brook, the conduit and the runnels with the city council's drainage engineers and operations department, regularly clearing leaves and debris ensuring they run clear.

The city council also manages Nine Wells nature reserve. Much of the work is carried out by volunteers.

"The runnels are a listed structure, so you can't just turn up with a cement mixer to repair them," Mr Latham said.

"Modern working techniques would require us to take up a chunk of the carriageway, but this is one of the main routes into Cambridge. It would be a rolling programme of years just to do the west side."

Hobson's Conduit supplies water to the lake in the Cambridge Botanic Garden as well as the ponds of two colleges

The conduit is also ecologically significant. A public "bioblitz" carried out in June, external close to Clare College sports round identified more than 160 animal and plant species, including tawny owls and the poisonous deadly nightshade plant.

The trust comprises ecologists, geographers, historians - people with broad skillsets but focused on the environment and hydro-geology, Mr Latham adds.

"We all have a passion for trying to keep valuable things in a good and proper state at a time when the natural repositories of that effort are distracted by lack of money or time," he said.

"It's a great privilege.

"The concept of the conduit goes back to at least 1574. All being well the trust will still be doing its work 400 years from now."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published10 October 2022

- Published14 October 2022

- Published30 September 2018

- Published16 December 2018