Cost of living: The Peterborough mosque-run food hub at Ramadan

- Published

The food hub at the Husaini Islamic Centre opened in October last year

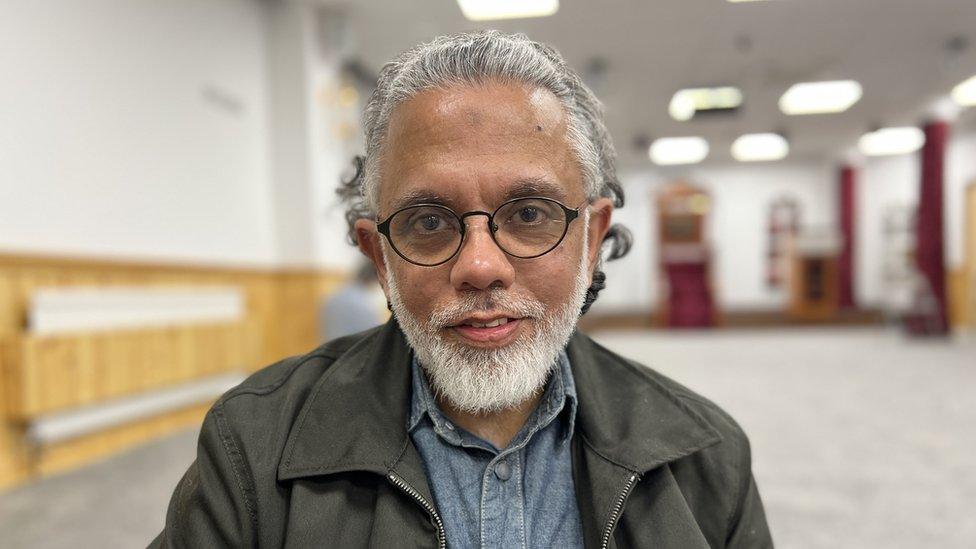

Since opening a food hub at his mosque last October, Rizwan Rahemtulla has endured sleepless nights.

Despite his long involvement in the Peterborough community, Rizwan has been shocked by the scale of need that surrounds him.

Most concerning of all, he says, are those who "for whatever reason, don't put their hands up".

"For me, that's the worrying part," says Rizwan, who is president of the Husaini Islamic Centre.

The hub - a walk-in pantry lined with tins and jars in the mosque's car park - opens on Thursday and Friday evenings.

At the beginning, it supported about five households.

Now, the hub's team of drivers delivers to 35 locations each week.

The hub is paid for using money given to Peterborough City Council through the Government's Household Support Fund

Rizwan says a fifth of the families supported come from within the mosque's own community.

The hub is one of about 20 similar schemes funded by Conservative-run Peterborough City Council using money from the government's £842m Household Support Fund.

Rizwan's phone rings. A mother-of-three is asking whether the hub is open this evening.

"Of course, sister," he tells her.

She has not been before and turns out to be a care worker, recently arrived in the UK from Nigeria.

"It's not like I don't have anything - I have rice," she says, clutching a bag filled with staples like fruit cordial, cornflakes and bread rolls. "But this is something that will help out - it's a huge help."

This is her first Ramadan outside of Nigeria.

"We're definitely going to do something for Eid," Rizwan tells her. "I'm going to order some cakes for the children and we'll cut the cake and we'll eat it together and celebrate."

The Husaini food hub is delivering boxes of food to 35 locations across Peterborough each week

Inside the mosque, the call to prayer, gathering worshippers and boys handing out khajoor - dates: the traditional way to break the fast.

"When it gets to this time where you know you've only got 15 minutes before you break your fast," says Rizwan, 54, "you feel the hunger and pain and so it teaches us a lesson.

"At least this evening, I'll be having a meal. At least this morning, I had a breakfast.

"There will be people out there who wouldn't even have had that and, if they did, it would probably be just be one small piece of fruit or a piece of vegetable.

"So it's an opportunity for us to be able to suffer some of that."

Akil Dhanji says his father used a food bank shortly after his family moved to Peterborough

Akil Dhanji, 58, delivers food for the hub.

Over chicken and potato curry and sweet tea, he recalls his father visiting a food bank back in the 1970s as the family settled in Peterborough having fled Uganda.

He remembers waiting outside a church off the city's Lincoln Road as his father went inside before reappearing with sugar, a block of butter, milk and bread.

Some in his family never knew about these trips to the food bank.

"Dad concealed it," Mr Dhanji says. "Being the head of the house and not being able to provide for the family is a difficult thing."

That stigma is partly why the hub offers to deliver – they don't want to put anyone off who may feel embarrassed about coming forward.

Vera Gouveia went to the food hub after a food bank said they could only help her three times

Among the stops on tonight's route is a low-rise block of flats just south of the River Nene. Vera Gouveia, 67, and neighbour Salimato Djalo live here.

A former factory worker from Portugal, Vera has the lung disease COPD and has lived in the flats for 12 years and in England for 22.

She unpacks cans of peas and sweetcorn, rice pudding, bread and cucumber.

"It's a big help - the cost of living - I'm retired, so this helps a lot," says Vera.

She first approached the food hub after being told a food bank could only help her three times.

What would she do without it?

"I don't know. I would eat less."

Her biggest struggle after settling her bills, she adds, is paying for food.

And the rising cost of living?

"It's horrible. You go to the supermarket and you see the prices - every day the prices go up, up, up. It's horrible."

A few doors down, the sound of Salimato's two sons watching - and playing - football in the lounge bleeds into the kitchen.

Salimato Djalo says the weekly food delivery means she has more money to help pay household bills and buy her sons clothes

A part-time worker at a supermarket warehouse in Thrapston, Northamptonshire, Salimato is also feeling the squeeze.

The food delivery helps ease the financial pressure, she says, from household bills and the costs of clothing for her boys.

"Every week, they bring good food. Always, I'm saying thank-you. They help me too much."

Rizwan offers to bring her some khajoor to eat after a day's fasting.

After a day of fasting Muslims share a meal together known as Iftar

Peterborough's cost of living support hubs have funding until March 2024.

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer has said the cost of living crisis is "not inevitable" and that if his party was in government it would use money from an increased windfall tax on energy companies to freeze council tax.

Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats accused the government of making the cost of living crisis worse with "unfair tax rises and cuts to essential public services".

The Green Party is calling for £1 bus single bus fares in England and 35 hours a week of free childcare from the age of nine months.

The Husaini hub, which received two grants worth a total of £18,000, currently supports 35 households.

"I never thought that there would be this many," Rizwan says.

"If you think about it, we now have - with the support of the city council - around 20 hubs in Peterborough and all of the hubs are very, very busy.

He does a quick calculation: 35 x 20 = 700.

"That gives you a figure for how much need there is," he says.

But Rizwan also knows there are those who, whether as a result of pride or fear, are not asking for help.

"These individuals are suffering in silence," Rizwan says.

"That weighs on my mind and I sometimes have sleepless nights about that. What I want is for everyone to be able to just ask."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published23 March 2023